Image: Flowers of the Mineral Kingdom cover. Reprinted by permission of Vandall King.

On the “Flowers of the Mineral Kingdom” Facebook group and on Pinterest, collectors and enthusiasts post photos of minerals that resemble flowers or are flower-like in their delicacy and beauty. Specific mineral species that look like flowers are also called by names like “desert rose” or “azurite blossom.” Two well-received books by the collector and amateur historian Van King, entitled Nature’s Garden of Crystals and Flowers of the Mineral Kingdom, are illustrative examples of this interest. A lily blooms in a single year and calcite crystals over millions of years, but comparing them—or indeed, calling one by the name of the other—is not uncommon among these mineral collectors.

Image: Rhodochrosite photo on Pinterest. One commenter says: “At first glance, I thought this was a photo of some peonies or pink roses clustered together.” Accessed July 10, 2015.

What compels mineral collectors to make this comparison? I believe that comparing flowers and minerals highlights both the juxtaposition and the utter difference of biological and geological being. This awareness provides an example of the parallax effect (the apparent displacement of an object when viewed from different positions) aimed at in contemporary discussions of ontology and world-making. The inclusion of rocks and minerals into discussions of ontological politics helps to make other ontologies thinkable and discussable.

The categories “animal,” “vegetable,” and “mineral” and the creation of corresponding disciplines of zoology, botany, and mineralogy/geology suppose the distinction between living and non-living things as one of the fundamental principles of the world. However, this does not mean that the distinction between things that are or were alive and things that never were is entirely self-sustaining. It requires some tending and pruning at the border. The science of mineralogy and the hobby of mineral collecting are central sites for this labor, as these are the activities of those in charge of “the inorganic slot,” to paraphrase Michel-Rolph Trouillot (1991).

Mineralogy and its cousin geology focus on mostly inorganic elements and compounds that are formed through chemical bonds and physical forces like sedimentation, pressure, and heat. These minerals are the precipitate of multiple dynamic forces and actions at the micro and macro levels upon objects that are not created by humans and that, for the most part, do not have and never have had life. But mineral collectors, like those who posted the photos shown here, frequently speak of these “non-living” entities as if they were living—pointing out how much a calcite “looks just like a FLOWER!” or a rhodochrosite “blossom” “looks like a beautiful flower… isn’t Mother Nature wonderful.” In my work on collectors and curators of minerals from Mexican mines, and with miners who work in around those mines, I frequently encountered such comparisons, such as to minerals as flowers, trees, “landscapes,” and other biological forms, either in the everyday register found on Pinterest and similar sites, or in scientific language such as “dendritic” (treelike).

Image: Pinterest photo of rhodochrosite. Comment: “Looks like a beautiful flower… earthshaped: Rhodochrosite ‘blossom’ Wolf Mine, Betzdorf, Siegerland, Germany. Isn’t Mother Nature wonderful…” Accessed June 5, 2015

One could look at this interest in minerals as flowers as a kind of comparison, perhaps strategically deployed. This would mean seeing how mineralogists, collectors and mining technicians use a language of the organic to understand and know the world of the inorganic, and to convince others of their understanding and knowledge. It would mean reading these analogies as “strategic biologism.”

I propose an alternative approach that would see the analogy between organic and inorganic life as more independent, more irreducible, more “otherwise” as Elizabeth Povinelli has put it (2013). This way of thinking suggests that the work mineral collectors do when they compare rocks and minerals to the organic world is not to avail themselves of the power of the organic or to see rocks and minerals “in terms of” plants and animals, but to think about growth and change in the inorganic world as analogous to, but utterly different from, growth and change in the organic world. This analogy between minerals and flowers provokes pleasure because of the similar result of two processes experienced as radically different, because on different sides of the boundary between life and non-life.

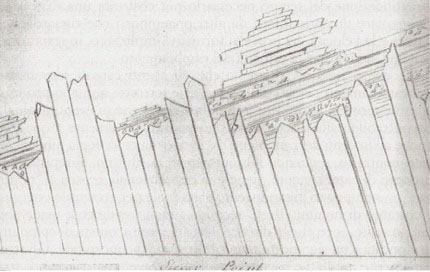

Image: Sketch by Sir James Hall of Siccar Point, site of the the geological unconformity on the basis of which Hutton built his theory of uniformitarianism. On the experience of seeing Siccar Point, John Playfair wrote, “The mind seemed to go giddy by looking so far into the abyss of time.” Reprinted by permission of Sir John Clark, Bart. of Penicuik.

In “Geontologies of the Otherwise,” her contribution to a 2013 Cultural Anthropology forum on “the Politics of Ontology,” Elizabeth Povinelli writes “ontology has been defined through…problems…which create and presuppose a specific kind of entity-state, namely life. In the natural, social, and philosophical sciences, ‘life’ acts as a foundational division between entities that have the capacity to be born, grow, reproduce, and die and those that do not: biology and geology, biochemistry and geochemistry, life and nonlife. Ontology is, thus, strictly speaking a ‘biontology.’”

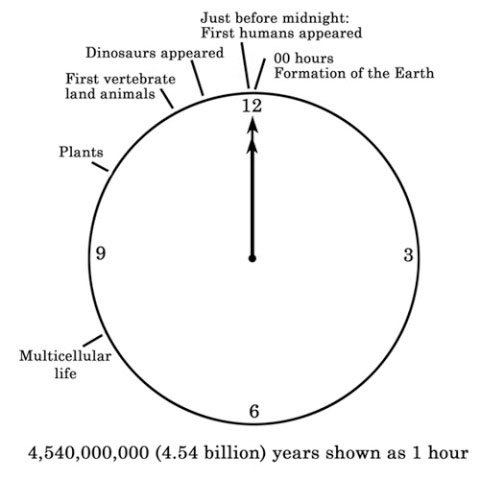

Image: Geological Clock, “4.54 billion years shown as one hour. Just before midnight, humans appeared” reprinted by permission, Suffolk Humanists and Secularists.

Here is where geological time comes in, by showing the enormity of the differences that converge in a particular mineral that looks like a plant or flower. The formation of minerals through geological processes, the growth of gypsum crystals over time that look like roses grown in a single season draws on the formal similarity of these processes, but at a vastly different time scale. In making these distinctions and connections, people are not denying the ontological difference between minerals, plants, and animals, but underscoring it. This entails a willed displacement of perspective, which is opened up, at least momentarily, by the impression of untold ages of geological time within which what appear in our more limited time frame to be static forms are constantly heaving, bending, growing, decaying, building up, and melting away. For the instants during which we grasp at that vast time scale, we catch a glimpse of worlds that differ from the worlds of plants and animals, of ontology beyond biontology.

References

King, Van (2011). Nature’s Garden of Crystals. Newryqs Press, Rochester, NY

King, Van (2013). Flowers of the Mineral Kingdom. Newryqs Press, Rochester, NY

Playfair, John (1802) Illustrations of the Huttonian Theory of the Earth. Edinburgh: Cadell & Davies

Povinelli, Elizabeth A. (2014). “Geontologies of the Otherwise.” Fieldsights – Theorizing the Contemporary, Cultural Anthropology Online, January 13, http://culanth.org/fieldsights/465-geontologies-of-the-otherwise.

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph (1991). Anthropology and the ‘Savage Slot:’ The Poetics and Politics of Otherness. In Richard Fox, ed. Recapturing Anthropology: Working in the Present. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press.

Elizabeth Ferry is Professor of Anthropology at Brandeis University. She has written about silver mining, mineral collecting, patrimony, resources, and temporality. She is currently working on a book about the materiality of gold in financial markets.

1 Comment

Fascinating, thank you for sharing your work. I’ve always been interested in what ethnography of crystals and crystal users/collectors/etc. would look like – especially around books and practices like “Love is in the Earth: A Kaleidoscope of Crystals” which explicitly talk about crystals as being alive.

1 Trackback