It’s not a new idea, but the term “influencer” likely has not crossed the desks of those outside the world of marketing and advertising. On the surface, it’s a relatively straightforward concept: some individuals have more of an audience online than others. Among these, some have a knack for recommending products or services that are then purchased by others.

For anthropologists and media researchers, the concept of an influencer recalls Bourdieu’s theory of social capital, and is a contemporary example of the kinds of influence addressed in social and actor/network theory (see here and also here). Attempting to understand the social uses of technology without considering monetization and the role of commerce is to ignore one of the strongest forces driving interpersonal dynamics online. Therefore, my intention here is to argue for both the relevance of “influencers” as an emerging concept, but also to highlight the ways in which it extends historical advertising concepts.

The idea extends beyond the interest of brands wishing to persuade more people to try ordering underwear online (for example), and into the broader world of ideas. What initially seemed to me like a straightforward transaction turns out to be the stuff of major media discussion, “influencer management platforms,” and so forth. It turns out there is a whole industry devoted to identifying and ranking influencers, and dissecting the best ways to court their favor. This article from Forbes is representative.

These are actors whose cooperation is uncertain, and goodwill contingent on the right compensation. In other words, the influencers are the most difficult of advertising targets: savvy and experienced in evaluating marketing campaigns, aware of the power of branding and how to build an audience. Individual product/service categories have their own influencers: while services like BzzAgent attempt to leverage the power we all have to make recommendations to one another, influencer-managers promise access to those whose opinions presumably count more (“digital superstars” as one article calls them).

There’s even a film about the role of influencers.

The roots of recent efforts (a glimpse):

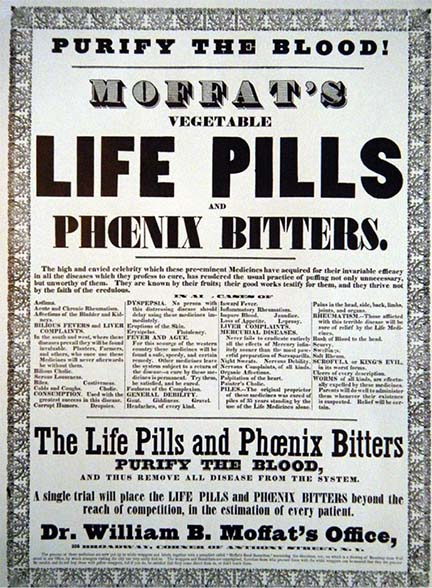

In a past life I taught graphic design—and studying compelling advertising campaigns was a big portion of our (and most design) curricula. We always started by looking at ads such as this one, from the 1800s:

Image © etsy.

One of the signature features of one of these ads was the amount of copy they contained. Much like those sponsored “articles” that can currently be found in magazines, these resembled newspaper articles in their appearance. A long description was a chance to persuade, to build credibility in the absence of (many) images. Advertisers felt the need to explain products to consumers and tout their benefits. Here, as we see in every stage of advertising history, the nature of ads was largely dictated by the technology available to assemble and reproduce them. This meant illustrations rather than photographs (until the late 1800s) and typographic hierarchy used to draw the reader’s attention in the absence of color.

Skipping way, way ahead

Since this is not intended to be a primer on the history of advertising (for a concise 60 second overview, watch this video and come right back), I am going to skip over the rise of brand-marketing and image-driven advertising and dive straight into the recent past:

During my dissertation fieldwork, Japanese interactive television related projects overwhelmingly included plans for how to incorporate advertising, recruit sponsors, and persuade audiences to consume the products of targeted brands. Like so much of contemporary online advertising, this process involved incentives. One program that I studied, Bloody Tube, went so far as to brand the simulated veins of a model with Sony logos, but its main strategy was to entice viewers to enter the program’s race by promising rewards in the form of Ponta points (Ponta is somewhat like a branded rewards card, but the rewards in this case can be used at any affiliated business). In a sense, this is just a continuation of the idea of “mailing in a contest form” (and other brand events) insofar as audiences must take a specific action in order to qualify for a prize, but it is also a model frequently used by contemporary blogs/websites.

Driving gracenote’s work on television advertising in particular, are efforts to use big data to match products to the known characteristics of audiences.

Image by author.

In other words, Toyota could deliver one in a series of targeted ads depending on the income level of a household, its members, and their genders. Such advertising is again merely an extension of something that already existed: web analytics-driven marketing, in which users of a particular app, or visitors to a site can be profiled, and spoken to as members of a narrower target audience.

Podcasts and Online Trend-makers

Ads conveying a sense of intimacy are, in a sense, an antidote to the big budget celebrity driven advertising seen since the late 20th century. While having Britney Spears sing and dance for Pepsi, is an example of one industry motif, an increasingly effective and employed model can be seen in the ads featured on Gimlet podcasts (for example). In one sense a throwback to the radio drama advertising of the early 20th century, these typically feature podcast hosts having (performed) casual conversations about a sponsored product/service, conducting interviews with employees of the sponsors’ organization (that resemble those of the podcast itself), or bantering about a topic related to what a sponsor is selling, before promoting the sponsor directly. These ads are self-consciously rough around the edges; their lack of “ad agency polish” is part of their attempt to appeal to audience trust.

In a sense, the role of influencers is very similar; these are individuals who have built an online following by foregrounding themselves and their ideas. Once their taste has been legitimated by the willingness of audiences to visit their virtual island—to watch makeup tutorials or read project how-tos (for example)—audiences are more willing to take seriously an influencer’s recommendations about what else to consume. There are echoes of advertising’s history manifest in this process: lengthy textual descriptions of products and services recall the earliest forms of print advertising and resemble non-sponsored blog entries.

But there are also differences—as one article points out, with television (excluding the interactive frontier), the value of an ad was measured in the number of viewers to whom it might be exposed. Online marketing, after many evolutionary stages, has become less about sheer numbers of viewer/users, and more about how engaged these audiences are.

To sum up, one overview of the recent Advertising Week 2015 makes the argument that cooption of influencers is necessary because direct messages from brands are no longer considered credible. It increasingly takes someone whom audiences already trust (preferably not a traditional celebrity), approaching them in a format deemed more intimate, to drive consumer trends.