Shortly after giving birth to her son, Jessica[1] began to experience a health problem that she describes simply as “pain everywhere.” About one month after we initially met at Spirit Rock Meditation Center in Marin County, California, she elaborated on her symptoms: “Joint pain, muscle pain, stabbing pain, stinging pain, burning pain, tingling, numbness…chest pains, palpitations, dizzy spells, headaches. I feel like I’m going to have a seizure, or brain fog, fatigue.”

Many of the doctors she visited over the course of several years claimed these symptoms were normal postpartum reactions, while others dismissed her condition as anxiety or hypochondria. Jessica instinctually felt they were wrong, but over time she began to believe them, and doubted herself. Her bloodwork was fine, and the x-rays were coming up clear. Nothing was broken. There was no visible inflammation in her body. Part of the problem, Jessica explained, was that the doctors weren’t listening: They didn’t have the time, or the right tools, to figure out what was going on.

After much persistence, Jessica landed a referral to a rheumatologist who spent a full hour and a half listening to her complicated medical history and suggested that she might have fibromyalgia—a poorly understood condition that is bound up with stress and sleep-related issues. As one of many lifestyle changes he recommended, the rheumatologist encouraged Jessica to download and use the popular meditation app Headspace.

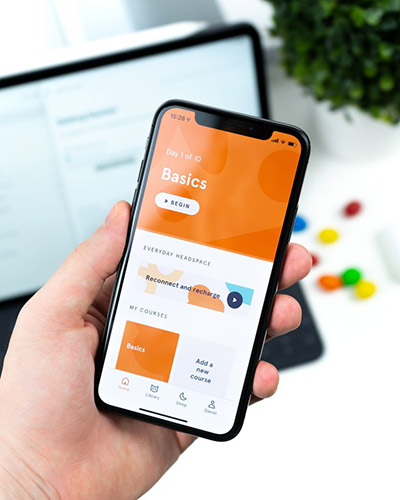

Headspace users are encouraged to begin meditating by listening to the 10-day basics course. Photo by Daniel Korpai on Unsplash.

“I just put my phone down and listen.”

Upon downloading the Headspace app, users are encouraged to complete a free, 10-day basics course that instructs them in the building block techniques of meditation. Each short, 3-10 minute audio recording typically has a focus: the body scan, watching thoughts come and go, focusing attention, and more. At the time of our interview, Jessica had been using the app for four months. One of her favorite features was the soothing British accent of Andy Puddicombe, the main “voice” and teacher of Headspace. However, Jessica never felt compelled to use Headspace in a structured way, instead choosing to adapt it to what she needs moment by moment, day by day. Sometimes, she doesn’t even meditate when she uses Headspace. Instead, she lets Andy’s voice play in the background while she listens and does other things, like checking her e-mail or washing the dishes—a usage pattern akin to that of podcast listeners (Sharon and John 2019). She doesn’t feel like she is doing anything wrong, explaining: “I feel like if I kept the tiniest takeaway, we’re doing good.” Jessica is 46 years old, and she considers meditation apps to be similar to other forms of technology-guided meditation she has used in the past—for example, Thich Nhat Hanh’s boxed set of meditation CDs, or the audio recordings that accompany Jon Kabat-Zinn’s mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) program.

Contrary to popular narratives and academic scholarship that assumes adopters of new digital health technologies are motivated by self-optimization, Jessica’s use of meditation apps is flexible and self-forgiving (Ruckenstein and Pantzar 2017). This unassuming, unidirectional interaction model of listening that Jessica prefers, however, might soon become obsolete. As meditation app companies move forward with their product roadmaps, their visions for health and happiness are shaped by an industry that dreams of a two-way conversation: one in which technology can speak back and personalize the user’s experience through voice-controlled artificial intelligence.

The personalized meditation assistant

Companies such as Headspace and Calm are part of a rapidly expanding, billion dollar industry that promises to guide users through complex mental and physical health conditions with a simple yet robust library of recorded meditations. Unlike the highly visual, data-driven technologies that have dominated recent digital health and wearable technology trends[2], most meditation apps facilitate a more qualitative, sensory mode of self-tracking whereby users learn to listen to their own bodies and minds through the act of listening to their smartphone[3]. For the past year, I have ethnographically observed how popular meditation app companies reframe seemingly commonsense concepts such as health, happiness, mind, and self through the design and strategic visions of these tools.

While the majority of meditation app companies don’t collect embodied physiological data, they are in fact “listening” and paying attention to users in other ways. In December of 2018, I attended a public-facing event hosted by Headspace in their new California Street office in downtown San Francisco. The company had recently acquired a San Francisco-based voice startup called Alpine.AI, to make strides towards building an app that could become a true meditation guide—one that answers questions from students.

After mingling over appetizers and drinks, several Headspace employees line up at a screen to give short, 10-minute presentations of their work. Soon the Vice President of Emerging Products, Alex Linares, takes the stage. Alex co-founded Alpine.AI, and joined Headspace through its acquisition. He excitedly introduces Headspace’s plans for personalization through a voice-based, AI-driven digital assistant that will run on increasingly widespread platforms such as Amazon Echo and Google Home. Their goal is for users to interact with the app ambiently within their homes, through conversation, which Alex considers to be “the great equalizer.” Alpine.AI was designed to make voice-enabled search more useful, and adopting this technical functionality will help guide Headspace users along “their unique journey” towards health and happiness.

Headspace’s move towards personalized voice interaction is framed as a response to market predictions of the increased adoption of in-home digital assistants, such as Amazon’s Echo Dot. Photo by Rahul Chakraborty on Unsplash.

Alex goes on to explain that any user of a meditation app will have two questions: “Where do I start?” and “What do I do next?” In order to help millions of people answer these two questions, Headspace will inevitably need to ask users questions and learn more about them. As more and more people go through this “loop” of self-disclosure and app usage, “the more interesting it becomes from a machine learning perspective,” Alex notes. Disclosing information about mental and emotional states, life problems, and the efficacy of certain guided meditation content is framed as not only helpful for recommending new content to the individual, but is justified as the ultimate act of altruism: giving Headspace this personal information will allow the company to help other people who are suffering, too. This, in turn, will “improve the health and happiness of the world”—the official mission of Headspace [4].

What’s in a voice?

While technology companies often frame personalization through AI as an inevitable result of market trends that will surely benefit society, the meditation app users I have interviewed express deep skepticism about AI’s ability to facilitate a meditation practice. Using aggregated data to help individuals on their path to personal growth assumes that a person’s deepest problem is a lack of relevant information. This assumption has been the subject of STS critiques of the technology industry for decades (Winner 1984), yet it continues to undergird popular discourse and drive technological design and innovation.

Contrary to this informatic model of learning espoused by many members of the technology industry, app users and meditators I have encountered throughout my fieldwork have articulated a different basis for a meaningful teacher-student relationship—one that is characterized by forms of presence and care that a digital assistant might not be able to provide. By listening to someone they can relate to, seeing and hearing a calm, centered person, and feeling that this person cares about them, they are able to persist in the otherwise arduous, confusing practice of meditation. To these students, the voice of their teacher (whether heard in person or through an app) is not merely a conduit of knowledge, or an answer to their question. It is a lifeline that sustains them in their path towards becoming a better person.

Listening to users, and responding with alternatives

The implementation of personalized AI systems within health and wellness apps is not inevitable. Like many other profit-driven industries, these choices are “by design” (Schüll 2012). In fact, several established and emerging companies are experimenting with new modes of connecting students to teachers, and to each other [5]. As the meditation app industry expands and other digital mental health and wellness technologies emerge, ethnographers are in a unique position to examine the effects of these cultural discourses and practices on lived experience. Individual users are not the only ones implicated in these trends. Because apps are often designed to scale, they spread quickly and transform the social institutions that are presently adopting meditation as a preferred mode of self-care—including education, medicine, the corporate world, and more. As this cultural phenomenon unfolds, it becomes important to ask: How will the voices of meditation apps speak to people about mental health? To whom will they speak? And perhaps most importantly, how will they listen?

References

Ruckenstein, Minna and Mika Pantzar. 2017. “Beyond the Quantified Self: Thematic exploration of a dataistic paradigm.” New Media & Society 19(3): 401-418.

Schüll, Natasha Dow. 2012. Addiction By Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Sharon, Tzlil and Nicholas A. John. 2019. “Imagining an Ideal Podcast Listener.”Popular Communication, DOI: 10.1080/15405702.2019.1610175

Winner, Langdon. 1984. “Mythinformation in the high-tech era.” Bulletin of Science, Technology, & Society 4: 582-596. Pergamon Press, Ltd.

Endnotes

[1] The names of meditation app users have been changed to protect their identity.

[2] Popular examples include FitBit and the Apple Watch.

[3] One exception is the Muse brain-sensing headband, which uses EEG and other physiological signals to facilitate meditation.

[4] See https://www.headspace.com/about-us, Accessed May 31, 2019.

[5] Examples include Brightmind, Insight Timer, Journey LIVE, and Liberate—all companies experimenting with fostering community through technology. Additionally, Headspace hosted their first “live” group meditation through Facebook Live on May 30, 2019. It is unclear whether this was a one-time experiment, or part of the company’s long-term strategic plans.