This essay joins ethnographic fieldwork with a visual storyboard to explore speculative futures that arise from ongoing processes of dispossession and loss in the foothills of the Andes mountains in Central Chile. In 2022, local activists and community members from Putaendo took Los Andes Copper, the mining corporation responsible for the Vizcachitas mining project, to the Environmental Tribunal in Chile. They claimed that the corporation had failed to consider the presence of the Andean mountain cat in their environmental impact studies. This oversight could have serious and irreversible consequences for the local ecosystem and the water sources that sustain their community.

I first became aware about the case of the Andean cat two years ago through a colleague and friend, Kristina Lyons, who knew of my research interests, and brought my attention to the case filed in the Environmental Tribunal in Chile against the mining corporation. My ongoing postdoctoral research looks at rights of nature and ecological justice in Latin America, where I primarily focus on judicial matters that encounter animals and plants as stakeholders and participants. I approach the animals and plants in these legal cases not just as evidence in the process but as nonhuman actors who are actively present in the making of the case and discussions in the courts. In 2024, I finally embarked on a trip to meet the people who had filed the case and to learn more about the fight to save the cat.

Image 1: A photo of the Rocín River, Putaendo, Chile, during the summer. This image serves as a background to subsequent images. Captured in February 2024 by the author.

An Elusive Cat and A Pastoralist’s Knowledge

The Andean cat closely resembles a domestic cat. It has earned the nickname “the ghost of the Andes” due to its extremely rare sightings. When mentioned, people often mistake it for the colocolo, another Andean feline, or a puma. The Andean Cat lives in the Andes region that cuts across areas in Peru, Chile, Bolivia, and Argentina.

When I arrived in Putaendo in February, it was summer, not very hot but very dry. Looking out of the bus window, I saw a dried-up river. The rocks in the riverbed were a reminder of what used to be the Putaendo River. I could not help but wonder where the water from the river had gone. It appeared as if the river itself was lost. With a list of contacts shared by a friend, I was able to coordinate a trip into the mountains with an organization of pastoralists from Putaendo who took us on horses through the rocky terrain. Over the weekend, we camped, laughed, and sang in the mountains, surrounded by the immensity of the Andes, the clear skies, and their horses.

Pastoralists in the Andes Mountains practice transhumance, a tradition passed down from the Spaniards (Gil 2009; Razeto, Lea-Plaza, and Skewes 2022). Transhumance is a seasonal practice where cattle are taken to higher ground during the summer and moved to lower ground in the winter to protect them from the cold. Over the years, the number of pastoralists has significantly decreased for various reasons. Many people have moved to the cities for livelihoods and other opportunities. Additionally, climate change and drought have resulted in the loss of most of their animals. In 2019, pastoralists estimated that they lost around eighty percent of their animals due to severe drought.

However, local scientists have found the pastoralists’ knowledge of the landscape invaluable in their search for the elusive Andean Cat. They realized that evidence of the Andean cat was critical to building the case against the mining project. This cat lives in arid, rocky, and rugged environments with extreme temperatures and sparse vegetation. In 2021, scientists recruited the help of the pastoralists to better understand the landscape and placed camera traps. After using the camera traps for over a year, and 3150 pictures later, local scientists were fortunate to finally capture an image of the Andean cat near the mining pit. For me, this event felt like a moment when a cat, a man with a horse, and the battle at court all came together.

While riding a horse at night, I asked Hector[1] why he had joined the group of scientists searching for the Andean cat. He explained that they shared common interests. The local scientists were supporting organizations contesting the operation license for Vizcachitas Holding in court, and he was also against the copper mine. Like everyone else, he was concerned about the depletion of water sources, contamination, and the destruction of the mountain landscapes where he usually rode. He had learned about these mountains as a child while riding with his grandfather, a pastoralist.

“They approached me because they needed to set up trap cameras where the mining project is located,” he explained. While we rode the dirt road to the mine, we discussed navigating the mountains alone. “No one goes by themselves,” he said plainly. “The problem is that there are fewer pastoralists nowadays, and we don’t have enough people to go in groups as we used to,” he added. It was unlikely that the scientists could reach those mountains alone, which made the pastoralists’ knowledge and ways of life all the more indispensable to collecting evidence for the cat’s presence.

A Cat and a River Intertwined

We set our camp by the Rocín River, nestled alongside the quiyaye, an evergreen tree, which is unique to this region. The landscape, featuring grasslands and shrublands, is typical of the Southern Andean steppe, with sparse vegetation in the Andean Mountain range near the Argentina border. The presence of these trees and the flowing river felt extraordinary. Just a short distance downstream, the river was dammed. Shortly after, as the river transformed into the Putaendo River, the water was channeled for agricultural and livestock irrigation. As a result, the Putaendo’s riverbed no longer carries water except for occasional floods.

The struggle to preserve the cat’s habitat encapsulates a related struggle to protect the river. The mining operation, along with polluting the river and drilling into the aquifers, poses a significant threat to water in the region. As part of their strategy to contest the corporation in legal courts, local activists selected this incredibly charismatic animal to advocate for the cessation of mining activities and the protection of their water sources and ways of life.

One of the local activists and scientists involved in the legal strategy explained their search for the Andean cat. “We weren’t sure if the cat was here. We even conducted prayers and ceremonies to locate it. We performed rituals to express gratitude for the water.” After establishing a network of scientists from various fields—connecting knowledge, equipment, and volunteer work to create species inventories—they received news that the cat was sighted in a heavily degraded agricultural area. Despite being far from the mine, this was clearly a sign of something amiss. “These cats typically inhabit high altitudes and rocky areas, so it made no sense that one was found near people at 800 meters above sea level. Therefore, we asked the mountain to reveal all its hidden wonders to help us achieve the protection we sought.”

Her words took me by surprise. I had not anticipated a scientist to draw out a spiritual relation with the mountain. I was reminded of Radhika Govindrajan’s (2018) work on relatedness, where she emphasizes that humans and animals are interconnected across multiple realms of political and ethical relations. Here in the Andes mountain, the cat, the community, the scientists, and the river would also share their losses and victories together.

In this context, the relationship with the cat can be seen as marginal, but despite its elusive nature, the cat is undeniably present in the community. What I came to understand is that at risk of being lost is not just the water but also the alienation and companionship between humans and other species (Berger, 1992, 6). To be more specific, the relationship between the community of Putaendo, the Andean cat, and all other living beings in this part of the Andean mountains is put at risk by the mining project.

In the following visual storyboard, I create images as speculative futures to consider the possibilities of seeing histories and loss through the landscape. Inspired by Aguilera del Castillo’s work on using multi-exposure photographs to speculate about subterranean histories in Mexico, I use the same technique to think about what will be lost in Putaendo if the Vizcachitas mining project reaches its full potential.

Image 2: Double exposure of landscape transitions. The photo overlaid on the original landscape shows the meeting point of the Rocín River and the Putaendo River. The water in the Rocín River flows freely until it meets the canalized the Putaendo River.

The scene of contrasting rivers forewarns what might be lost if mining operations persist. In Image 2, I used double exposure from photographs taken upstream, where the Rocín River originates, to downstream, where the Putaendo River emerges, to speculate how the push to intervene in the Rocin River in search of copper will bring about a future that presents massive ecological change and uncertainty. The final image draws attention to a striking contrast that presents a “virtual” witnessing of the river’s disappearance as mining activities take hold.

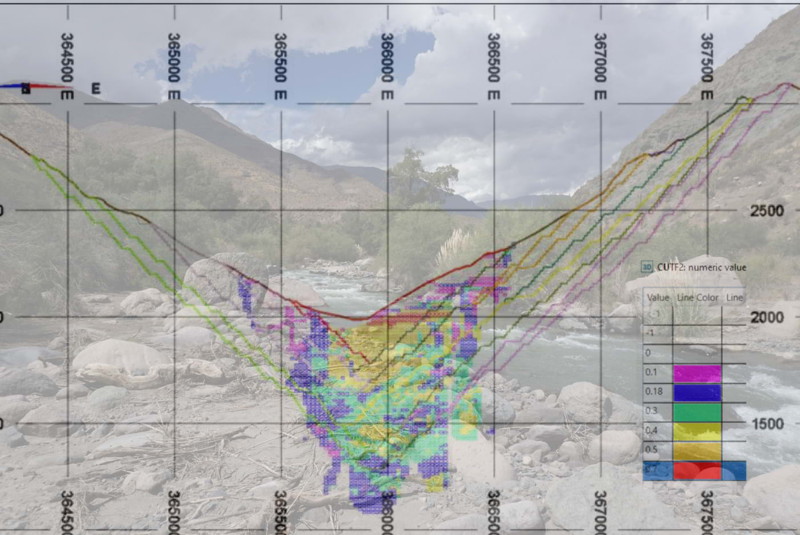

Image 3: Intervening the River. Double Exposure with Technical Report for Vizcachitas mine pit at Rocín River riverbed.

Image 3 overlays a photo of the Rocín River with an altitude and location grid for the Excavation Plan Design based on the Vizcachitas mine technical report.[2] The pixels represent the minerals. The color lines on the design represent the different phases of excavation. Red represents the initial stage and pink signifies the final stage. The numbers on the right illustrate that the excavation goes around 1500 meters deep into the mountain, from 2500 meters to around 1000 meters, both measurements above sea level.[3] Though prior sightings of the Andean cat had been recorded at 3000 meters, scientists attempted to locate the cat at 2100 meters to provide evidence in court that the cat’s habitat extended to the area of the mining corporation.

Image 4: River Rocín faces its future in the lost waters of River Putaendo. Double Exposure by the Author.

The report also stated that “the Rocín River must be diverted to start the mine operation,” which entails a diversion tunnel five meters in diameter and approximately sixteen kilometers long (Tetra Tech 2023, 18). With the enormous size of the mine pit, I was led to think about the end of the vegetation, including the quiyaye, and the river. Image 4 speculates a river that has lost its water, because the court battle hinged on territorial evidence to save a cat without recognizing the intertwined ecological and political lives of the animal, pastoralists, and the river. The free-flowing river is barely discernible in the image, yet a bridge stands over the gravel-like surface, in a nostalgic reminder of a river that used to flow beneath it.

Image 5: Speculation of the drying up of the River Rocín. Image 1 was edited to leave only the rocks, as was the case for the Putaendo River.

In 2022, Chile’s Environmental Tribunal granted precautionary measures to temporarily suspend Vizcachitas mining operations for the duration of the lawsuit against the company. However, in 2023, they were allowed to operate again. In the final image of the story (Image 5), I take the image of a dried up Putaendo River and duplicate it to show how the trees rise in the distance but are fore fronted by sudden overhaul, bringing the reader to ruminate on all that will be lost.

What Will Be Lost

The text acknowledges the significance of the cat’s presence for Putaendo, its mountains, its people, and other beings. Even though it’s not visibly depicted in the pictures, the cat’s influence is omnipresent throughout the entire text. To illustrate, consider yourself in the African Savanna; you know that lions are somewhere. Even if you can’t see them, the mere thought of what they could do permeates their presence. Conversely, think about the same lion in a zoo. While visible, the lion’s presence is diminished. It’s so inconsequential that you might move on to the next exhibit without much thought. Applying this concept to the Andean cat, seeing the cat is not necessary to feel its presence.[4] There is no need to see it to understand that it sustains life in a place where everything is at risk. The cat’s presence unites everything—the water, the land, the people, and the aspirations for a future without mining.

Notes

[1] Names have been changed to protect the privacy of those involved in the case.

[2] Tetra Tech. “Vizcachitas Project Prefeasibility Study Vaparaiso Region, Chile NI-43101 Technical Report.” 2023. Santiago de Chile: Tetra Tech, page 252.

[3] Los Andes Copper acquired the rights to explore a copper, silver, and molybdenum mine near the Rocin River in 2007. However, it wasn’t until 2019 that the local community began a series of legal actions to stop the mine due to its impacts on the landscape and water sources.

[4] This idea of marginalization and presence is taken from John Berger’s chapter “Why Look At Animals” (1992[1980]).

References

Aguilera del Castillo, Pablo. n.d. “Subterranean Cartographies: Excavating Geography Through the Camera.” American Anthropologist (forthcoming).

Berger, John. 1992 [1980]. About Looking. Vintage International.

Montero, Raquel Gil. 2009. “Mountain pastoralism in the Andes during colonial times.” Nomadic peoples 13, no. 2: 36-50.

Govindrajan, Radhika. 2018. Animal Intimacies. Chicago University Press.

Razeto, Jorge, Isidora Lea-Plaza, and Juan Carlos Skewes. 2022. “Arrieros del Antropoceno en los Andes de Chile central: nuevas movilidades para continuar habitando las montañas.” Quaderns de l’Institut Català d’Antropologia 38, no. 2: 327-348.

Tetra Tech. 2023. “Vizcachitas Project Prefeasibility Study Vaparaiso Region, Chile NI-43101 Technical Report”, Santiago de Chile: Tetra Tech. https://losandescopper.com/site/assets/files/3685/techreport.pdf