On a recent trip to California I took the train down to San Jose to visit the Tech Museum of Innovation where a new exhibit focused on wearable technology and data—Body Metrics—had just been unveiled. I study the proliferation of digital self-tracking, a phenomenon made increasingly widespread by the popularity of sensor technology and wearable devices (think Apple Watch, Fitbit wristbands, or OMsignal shirts) that generate data about one’s self. In my research I pay particular attention to the way these new technologies of knowledge are shifting the way we think about and view our bodies so I was keen to see the way the museum expressed the relationship between data and bodies. My visit would become haunted, however, by another display of the body—the Body Worlds exhibit—that I had seen months earlier in New York City. Considered alongside one another, the two exhibits say a lot about the way we commonly conceptualize personal data.

Skinned Bodies

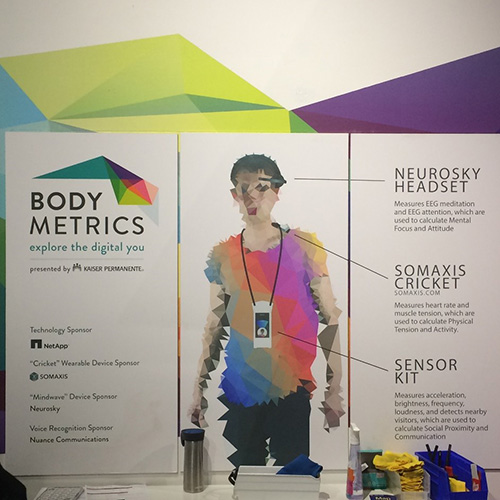

Matching the ambitious rhetoric issuing from Silicon Valley, whose spirit the Tech Museum had after all committed to capture, Body Metrics grabbed attention from the start, promising an “experience beyond anything now available to consumers.” The website beckoned would be visitors: “come and explore human data streams measured and made visible using a Somaxis EXG muscle and heart sensors, a wireless NeuroSky EEG headset, and a customized iPod,” devices whose healthcare and aviation inspired names alone were meant to stand testament to their scientific rigor and efficacy. More than a showcase of state-of-the-art technology, however, the exhibit offered a social commentary, instructing guests on ways to interpret their digital output in the halls of the museum, and later on in their daily lives. In particular, by keeping track of one’s physiological and psychological states through EEG, heart rate, muscle tension and geolocation monitoring, the museum proposed to broker access to one’s very psyche that doubled as the ‘digital you.’ Translating for the modern reader, one local review of the exhibit had expressed the high-tech rhetoric in more contemporary parlance: “in a snapshot” what the exhibit creates is “an internal selfie.”

Image: Body Metrics exhibit, on-premise billboard. Photo by author.

The appeal to self-discovery and self-excavation through the peeling back of surfaces was a familiar one. It closely mirrored the narrative presented at another attraction of the body, the entertainment derivative of the operating room: Body Worlds. Body Worlds is a long-running anatomical show that endeavors to bring knowledge of the body to the lay public. In particular, the exhibit prides itself on presenting bodies preserved through the technique of plastination in what it calls ‘natural’ poses. Never mind that the contortion of the elderly (all cadavers are of people who ranged from 60-90 years old at the time of death) and Asian bodies of anonymous donors into poses miming young, healthy and idealized Euro-American male postures—mimicking Rodin’s ‘Thinker,’ playing football, with the sole female body symbolizing procreation, made in fact for the most unnatural display.

Image: Football Gladiators. Copyright: Gunther von Hagens’ BODY WORLDS, Institute for Plastination, Heidelberg, Germany, www.bodyworlds.com

Meant to operate as real-life medical atlases, the skinned bodies are intended to prompt questions about one’s own body rather than the experience of these particular bodies. It is by stripping away both skin and social context that the exhibit, not unlike the devices I encountered at Body Metrics, promised to make the ‘interior face visible’. A manager confirmed the connection I would later sense between these truly exposed and vulnerable bodies and the more banal and administrative appeals of wearable technology displayed at Body Metrics. People come to this exhibit, he said, to learn about themselves, an idea only echoed in the prophetic slogan advertising the show in New York: ‘Destination: You.’

Image: Body Worlds pulse, Destination: You banner. Copyright: Gunther von Hagens’ BODY WORLDS, Institute for Plastination, Heidelberg, Germany, www.bodyworlds.com.

In their promises to move beyond surfaces in locating the body and the self, both exhibits also activate a familiar trope of the nude body that had long correlated ‘truth’ with the state of undress. Body Worlds takes the idiom to a literal extreme by suggesting that even the epidermis disguises. In one of the displays a corps tellingly holds out his own skin as a final, strange offering. The skin, an irrelevant barrier now, lays limply in his stretched out hand. This disguise shed, he stands entirely vulnerable and exposed.

Image: The Skin Man. Copyright: Gunther von Hagens’ BODY WORLDS, Institute for Plastination, Heidelberg, Germany, www.bodyworlds.com

At Body Metrics, the narrative of transparency equally looms large. In a poster that greets visitors at the start of the exhibit (image above), a boy is shown standing in a posture of readiness, wearing all three devices. His entire body is pixelated making his features difficult to discern. An attendant explained that this abstraction was meant to pay homage to digital privacy and I was likewise invited to distort my photograph, taken at the entrance, to create the desired level of anonymity. The blurry effect, though, seemed less to disguise than to reveal. The boy’s t-shirt, as though displaying thermal information collected from sensors embedded in clothing, explodes in a panoply of colors simulating a heat map. The geometric patterns that frame his shape evoke the crystals of a data visualization graph or chart, indexing the data of which his body appears to be composed. The result is an all but translucent figure supposedly stripped open by the digital gaze that sees past his visage and straight through to his body and his internal state.

Image: LifeQ promotional billboard. Photo by author; taken at CES 2015.

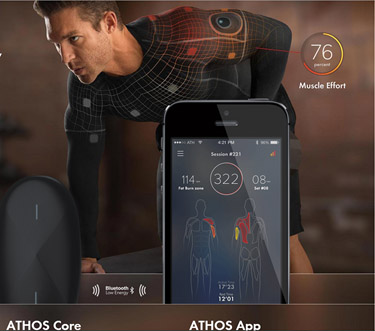

What struck me about these two on the surface very different corporeal displays is the way both exhibits claimed to make visible the inner workings of the body. At Body Worlds, when the skin is pulled back one discovers the internal machinery of the body. At Body Metrics, one finds data. The suggestive conflation between data, anatomy, and nudity is important to attend to, particularly as it informs the broader way in which popular culture, aided by marketing rhetoric, conceives of personal data. In fact, to explain the workings of their products to customers, many wearable technology makers make explicit connections between data and body matter by borrowing the visual language of the X-Ray or the CT-Scan. Device makers also often talk of ‘hacking’ the body, sourcing ideas of hacking from technical circles to suggest creative problem solving, but equally activating the more literal meaning of the term, implying a process of breaking or cutting something open. Meanwhile, proponents of ‘open’ technology as well as advocates of privacy compound the sense of exposure facilitated by data by regularly announcing the impending delivery of a transparent society, one in which every gesture, movement, and affect will be available for transcription and transmission along digital lines. Popular author Patrick Tucker therefore warns us to expect The Naked Future while the online campaign, NakedCitizens collaboratively developed by European privacy groups, similarly teaches its followers to understand one’s vulnerability in a digital climate in corporeal terms.

Image: Athos banner advertisement.

Through this connection, not only is data made to seem material and tangible, but the body is presented as a kind of repository of knowledge where information is stored in a manner similar to organs. When I asked one friend who is an avid self-tracker how she thinks of the body, she paused a moment then said with conviction: as a container. Asked to clarify she drew a large square in the air with her arms suggesting a storage cabinet. She sees the body as an input-output device—as a file cabinet, a database, really—where information could be added and when necessary, retrieved. And just like the body is made up of its individual but discrete parts, data is likewise often conceived as making up a ‘piece’ of one’s self and one’s body. Speaking about self-monitoring with the aid of various sensors, another friend suggested: “it’s like a puzzle I’m putting together.” The sheer variety of wearable devices coming to market cultivate the perception that each part of the body contains discrete information that the expanding range of sensors is simply helping to extract and document. When one’s personal data—like Humpty Dumpty—is put back together, one can become wholly reconstituted, but also in an important sense made whole again. In the more extreme technophile enclaves like the online discussion boards of transhumanist enthusiasts these views on data lubricate conversations about immortality where the expectation that one will one day be able to extract and upload all of the data about oneself to a device more permanent than the body and thus overcome death if not materiality, run amuck. But even in more mainstream discourse, the public face of personal data has become one of smooth and continuous emission that results from a straightforward extraction from the body.

Together these exhibits reveal the degree to which the digital gaze and the anatomical gaze have become paired in popular discourse. One is in fact often conceived as the logical extension of the other as though wearable devices now simply take over and extend the function of the scalpel as the instrument that helps to peel away layers of useless epidermis to reveal the ‘stuff’ within in ever more precise ways. Like the muscular body that is unveiled once the skin is pulled back, we often tend to default to thinking of data as an internal second skin running just under the body’s surface.

Veiled Logic

How appropriate is it to import these associations when conceptualizing personal data? There is certainly a genealogy, a set of overlapping historical strings that both tug at this popular imaginary of personal data and hold it together. To mention only a few strains, one could easily point to the legacy of cybernetics that had proposed to see the world[1], and later also the body[2] as a closed, self-contained and coherent system of information. The premise that one search for answers by plunging into a depth or by prying open layers, including the skin, extends even farther back, however, and has been foundational to both Western philosophy[3] and Western medicine[4] where the production of (self) knowledge has long relied on a movement from the inside to the outside.

There is much that gets lost and covered up, however, in thinking data as an analog of organs or as a parallel of the ultimately nude body, including the social processes through which data sets are produced. The exposed physical and symbolic membranes of the Body Worlds and the Body Metrics exhibits further propose to see the anatomical gaze as both universal and universally denuding, even though the language that compares digital data to extraction of body matter only reveals the cultural and historical logic that shapes the way we are often invited to receive and make sense both of bodies and data. It departs vastly, for instance, from body language offered by traditional Chinese medicine that instead privileged the skin and sought to interrogate the body by scrutinizing and mapping its surface. Rather than seeking to distill elementary forms and segment crisp categories, Chinese medicine historically unfolded a more webbed logic of interrelated flows and influences. Therefore the dynamic and multiple Eastern “mo” discerned by Chinese doctors could not be made easily commensurate with the rhythmic singularity of the pulse perceived by Western medics. Similarly the sculpted definition of the muscular anatomical body stands at odds with the fulsome, fleshy plentitude of the body articulated by principles of acupuncture.[5] The disjuncture between Chinese bodies and western paradigms is folded right into the folds of the Body Worlds exhibit where, ironically, it is the bodies of deceased Chinese elderly persons, all moreover preserved over 30 years ago, who are made to account for contemporary American and European life and politics.

The language of nudity, exposure, transparency, anatomy less describes personal data than sets the terms by which data is to be socially interpreted and understood. But if data is never raw[6] we need a new vocabulary through which to not only make sense of the increasing quantities of data and the ‘self’ that results, but also to set expectations of the data sets we receive and conceive. To do that, we very well may want to leave some skin in the game.

Endnotes

[1] Edwards, N. Paul. 1997. The Closed World: Computers and the Politics of Discourse in Cold War America. The MIT Press.

[2] Klines and Clyne who originally coined the term ‘cyborg’ imagined the body as a closed system, one that can be technologically harmonized and controlled. See: de Monchaux, Nicholas. 2011. Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo. The MIT Press.

[3] duBois, Page. Torture and Truth. New York: Routledge, n.d.

[4] Kuriyama, Shigehisa. 2002. The Expressiveness of the Body and the Divergence of Greek and Chinese Medicine. Zone Books

[5] Kuriyama, Shigehisa. 2002. The Expressiveness of the Body and the Divergence of Greek and Chinese Medicine. Zone Books

[6] Gitelman, Lisa. 2013. Raw Data is an Oxymoron. MIT Press.

Yuliya Grinberg is a PhD candidate in the department of anthropology at Columbia University. Her work examines self-tracking and personal data on mobile apps and wearable tech, especially data aesthetics and the relationship between data and embodiment.