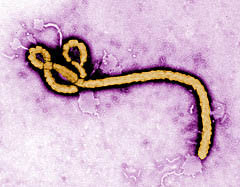

The Ebola Virus Photo: CDC Global

When I began writing this brief statement in mid-September, 2,630 deaths had been attributed to probable, suspected, or confirmed cases of Ebola. The World Health Organization projected as many as 20,000 cases in the West African region before the outbreak could be brought under control. The epidemic had received little news coverage and felt, to many in the U.S., as yet another disaster taking place in countries reputed for their many dangers. By mid-October, 4,033 Ebola deaths had been reported by the World Health Organization and projections on number of cases had risen to 10,000 per week in West Africa. Concerns are heightening that the epidemic may be a greater threat than originally perceived. The number of news reports providing coverage on the epidemic has increased exponentially, reaching over 30 million by the beginning of October. This dramatic increase appears to be spurred by the death of Thomas Eric Ducan, the first reported death occurring outside the epidemic hotspot of West Africa, which made headline news around the world and sparked fears that the epidemic could spread out-of-control around the globe.

This tragedy highlights the current state of global health inequities and the role of discourse (in this case media initiated) in directing the actions of global health institutions. The virus has raged across the West African region since March, with the initial case linked to a child, known only by the epidemiological term – patient zero – who died in December. It took until August of the following year for the United Nations health agency to declare an international public health emergency, and admit the need for a coordinated regional response. In September, David Nabarro, UN Coordinator for the Ebola Response, announced that that United Nations system was working on a 12-step global response plan. Prior to this, local governments have been left to manage their outbreaks with limited resources and staffing, relying on international NGOs and missionary workers to assist with the ever increasing burden on already inadequate systems. Why has it taken so long to initiate these efforts? Might the outbreak have been contained, and many lives saved, if a coordinated regional response was initiated earlier? And what about the infected U.S. nurses, was it ignorance that an epidemic was taking place somewhere else in the world that resulted in inappropriate actions and poor preparation? This Ebola outbreak is yet another example of the continued global inequities that exist, not only in resource distribution, but also in whose voices are heard and how life is valued.

Ebola, like other rapidly transmitted viruses including SARS and H1N1, have provided the story line for many medical thriller movies including Outbreak (1995), The Ebola Syndrome (1996, Hong Kong), Contagion (2011), 12 Monkeys (1995), 28 Weeks Later (2007), the opening scenes of And the Band Played On (1993) and the mini-series Pandemic (2007). These fictional accounts portray the devastation of lost loved ones, the fear of the unknown, the threat of the potential (or actual) annihilation of whole societies, and the scrambling by government health institutions, as health workers, research scientists and policy makers rush to find an answer, a cure or vaccine. In these accounts the biomedical agenda takes whatever means necessary, including quarantines, trial drugs, blood transfusions, even time travel, to save the fate of entire populations.

While this is the stuff of fiction, these stories are on not unlike the current events taking in West Africa. And, as unlikely as these events seem to those of us who have experienced a disease outbreak only from the comforts of living rooms and movie theaters, they are the current reality to people in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leon. Boarders have been closed. Flights from affected countries have been diverted. Certain nationals are not given entrance to other countries. A mandatory three-day lockdown has taken place in Sierra-Leon to give 30,000 health workers the opportunity to locate potentially infected individuals and distribute soap to households.

Sierra Leone — Protesting the Ebola shut down of Sierra Leone Photo: David Holt Attribution-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-ND 2.0)

Living in such fear, it is not surprising then that public reactions to disease prevention interventions have not been positive. A team of eight medical workers were attacked and killed by villagers in Guinea earlier this month. Critics of the Sierra Leon lockdown have argued that it will destroy public trust in doctors. People are resisting going to the hospitals for fear that that is where disease transmission takes place (and in the U.S. it is). Every major Ebola outbreak has been met with local resistance, hostility and rumor. In 2002, an international team of experts fled a village in Gabon when threatened with violence. In the 1995 outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the link between the hospital and those dying of Ebola stimulated the popular rumor that doctors were murdering workers who had smuggled diamonds out from the nearby mine. In the Ugandan outbreaks in 2011 and 2012, locals believed that white people sold the body parts of the victims for profit. Consequently, western medical staff were viewed with suspicion and suspected of bringing the disease to the country.

Perhaps as a result of these past experiences, and the relationship between Ebola transmission and cultural practices from the region including burial rites that expose individuals to infected bodily fluid, international health agents initially expressed an unease interfering with the most recent outbreak. In many parts of the world the deployment of biomedicine has been met with incomprehension, suspicion, or outright resistance. Historians have documented local responses to the introduction of new biomedical approaches and the associated public health campaigns to which Africans were subjected. In East Africa, for example, local rumors of vampires were linked with anti-sleeping sickness campaigns (White 2000). Given that lymph fluid was extracted using large needles for analysis by European public health workers, the vivid imagery of blood-sucking Europeans was in fact literal not just metaphorical. In the Belgian Congo, people would flee into the bush to escape the mobile public health disease eradication teams, or persuade traditional physicians to remove their lymph nodes so that they would not be subjected to the dreaded needles (Lyons 1988).

In contemporary society, echoes of the legacy of biomedicine as an extension of the oppressive colonial apparatus continue. In northern Nigeria in 2004, a campaign to eradicate polio through universal vaccination was abandoned due to widespread rumors that the vaccine was a western plot aimed at sterilizing Muslim women, and infecting children with HIV (Jegede 2007). In South Africa, conspiracy theories suggest that HIV was developed by the CIA to kill Africans (Niehaus and Jonsson 2005). In Guinea, villagers distrust the government and international community, believing foreign health care workers are part of a conspiracy in which the Ebola virus has either deliberately been introduced, or invented as a means of luring Africans to clinics to harvest their blood and organs.

Sierra Leone: into the Ebola epicentre

Photo: European Commission DG ECHO

Attribution-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-ND 2.0)

Such rumors, paranoia and defiance of international biomedical expertise, to some might seem like the response of scared or ignorant people. However, we might consider these beliefs and actions an indicator of global power differentials, and the seemingly neutral technical methods of biomedicine’s involvement in maintaining these distinctions, in-line with Gramsci’s concept of ‘cultural hegemony’ (Forgacs 1988). Westerners are evacuated and treated with life saving drugs that at present have been denied release to affected countries, deemed untested and thus unsafe by global authorities. African bodies are left to suffer without treatment, their unknown fate in the hands of god (or their own body’s immune system).

This situation, even more so than the HIV pandemic, has put in sharp relief the imbalances that exist in global health, what Hӧrbst and Wolf (2014) call the unequal “medicoscapes” of current biomedicine. Diseases can no longer be regarded within locally isolated frames of reference, expected to remain in small villages where deaths of hundreds or thousands will go unnoticed. Bob Dylan sings, how many deaths will it take before we realize that too many people have died? Indeed, we are all members of a globalized state, yet as this epidemic again reveals, the lives of Africans appear to hold lower value and the voices of Africans in their appeals for help remained largely stifled and unheard until the epidemic reached U.S. and European shores. Speaking 34 years ago, Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, the 1970s Nobel Prize winner for Literature, noted that “divergent scales of values scream in discordance …. Which is why we take for the greater, more painful and less bearable disaster not that which is in fact greater, more painful and less bearable, but that which lies closest to us. Everything which is further away, which does not threaten this very day to invade our threshold … this we consider on the whole to be perfectly bearable and of tolerable proportions.”

References

Forgacs, D, ed. 1988. An Antonio Gramsci Reader: Selected Writings 1916-1935. New York: Schocken Books.

Hӧrbst, V, and A Wolf. 2014. ARVs and ARTs: Medicoscapes and the unequal place making for biomedical treatments in sub-Saharan Africa. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 28(2):182-202.

Jegede, AS. 2007. What led to the Nigerian boycott of the polio vaccination campaign? PLoS Medicine 4 (3):e73.

Lyons, M. 1988. Sleeping sickness, colonial medicine and imperialism: Some connections in the Belgian Congo. In Disease, medicine and empire, edited by R. Macleod and L. Milton. London, UK: Routledge.

Niehaus, I, and G Jonsson. 2005. Dr. Wouter Basson, Americans, and wild beasts: Men’s conspiracy theories of HIV/AIDS in South African lowveld. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 24 (2):179-208.

Solzhenitsyn, A. 1970. The Nobel Prize in Literature 1970. http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/1970/solzhenitsyn-lecture.html

White, L. 2000. Speaking with vampires. Rumor and history in colonial Africa. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

1 Comment

It is actually the “stuff of fiction”. Your clue is “… It took until August of the following year …”. One reason was that “to save cost” the hemorrhagic fever division of the World Health Organization had just been all but dismantled and its expertise let go prior to the outbreak. The WHO lacked appropriate “antennae” to e.g. form a picture, like in these movies, of what one or two cases in a certain area might mean a few months down the road. So we had to wait for these critical months to pass until “any other epidemiologist” could see the trouble on the horizon too. And seeing that no further “intelligence” is forthcoming other than screening people for fever symptoms at arrival (!) airports, we may have to wait until the first Ebola carrier infects a thousand people in a “developed” country all at once …