This post is the first in a two-part series on water management in New Orleans.

In September 2013, just days after the eighth anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans officials unveiled a new approach to water management in the city: the Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan. After centuries engineering ways to exclude water from the city (through levees, flood walls, and drainage pumps), city officials now hoped to reintegrate water into the landscape. In building new ways of “living with water,” the authors of the plan hoped to create a more sustainable New Orleans—especially in the face of growing threats from climate change. But with many neighborhoods still rebounding from Hurricane Katrina, residents questioned what these restoration projects might mean for their communities. The story of water management in New Orleans is entangled with issues of race and class, infrastructure and development, and the politics of sustainability—issues that, as recent flooding in Baton Rouge remind us, are not going away.

Mud, mud, mud…

In 1819, Benjamin Latrobe, architect of New Orleans’s first waterworks, wrote in his journal: “mud, mud, mud… This is a floating city, floating below the surface of the water on a bed of mud.”

He wasn’t joking. At the time, the only suitable place for permanent settlement was a narrow strip of high ground along the Mississippi River. The rest of the city was covered by cypress swamp. This waterlogged landscape was viewed as a dark—even dangerous—place. It was rumored to be a site for voodoo rituals, a hideout for marooned slaves, and a source of deadly miasmas. According to an 1840s visitor to New Orleans, the swamp was a “boiling fountain of death” and “one of the most dismal, low and horrid places, on which the light of the sun ever shone… belching up its poison and malaria, [which sweeps] through the city, feeding the living mass of human beings who stand there [with] the dregs of the seven vials of wrath.”[1]

Clearly, the swamp wasn’t seen in a positive light.

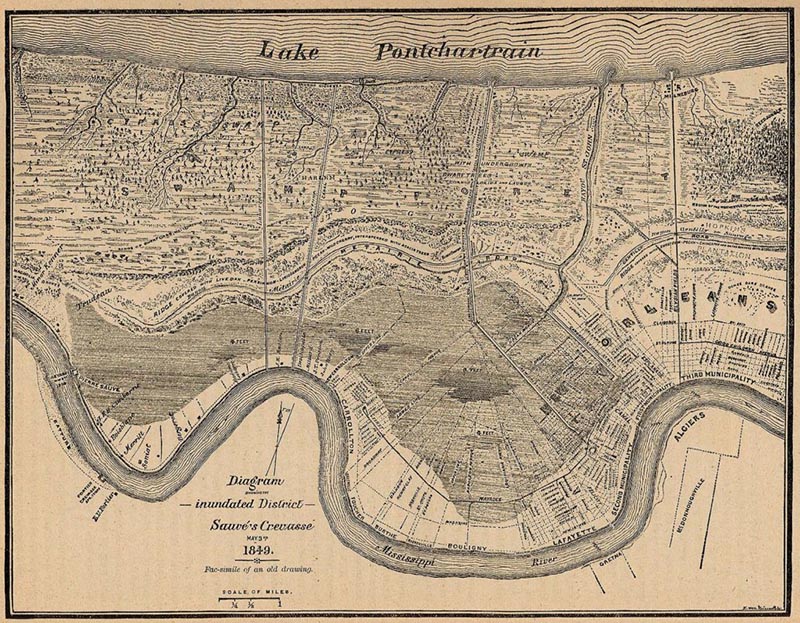

1849 map of New Orleans showing extent of cypress swamp behind city. From Wikimedia Commons.

For nearly two centuries, most New Orleanians settled on the dry land along the river. Areas near the swamp, known locally as the “back of town,” were only for the city’s poorest residents. But as the city’s population grew from 10,000 people in 1800 to almost 300,000 people in 1900, high ground became harder to find. The well-to-do were pushed closer to the city’s swampy edges. Supported by progressive and public health movements, real estate developers proposed draining the swamp, transforming the muddy frontier into stable land. While drainage advocates merely wanted to open up space for new housing, their efforts would alter the social, material, and racial landscape of New Orleans, and create the conditions for future disaster.

From swamp to suburb

At the end of the nineteenth century, New Orleans officials began a massive effort to “reclaim” the swamp. Between 1879 and 1915, the city spent $27,500,000 on drainage projects, most of them carried out by the Sewerage & Water Board.[2] City engineers dug outfall canals and connected them to twenty-two pumping stations, which pushed water into Lake Pontchartrain. They also installed a maze-like system of drains and pipes to keep newly created land dry. Over the next few decades, real-estate developers built sprawling subdivisions with names like Lakeview, Paris Oaks, and Gentilly Woods.[3]

A pumping station in New Orleans. Photo by author.

Drainage projects transformed the city’s racial geography, deepening existing forms of segregation.[4] New subdivisions drew white flight from older, more racially-mixed neighborhoods, often excluding black residents through redlining or racial covenants. When middle-class black residents began moving to these neighborhoods after the end of de jure segregation, white residents fled to newly drained suburbs outside of New Orleans.

Drainage projects also transformed the city’s physical geography. After engineers removed water from the swamp, the new land began to subside or sink—in some places up to an inch a year. Areas that stood at sea level in 1900 soon fell to 10 feet below sea level, causing damage to homes, streets, and underground infrastructure. Subsidence also caused these areas to flood, even during light rainstorms.

The city had completed most drainage projects by the middle of the twentieth century, resulting in thousands of acres of new real estate. But keeping that land dry is an ongoing task. The Sewerage & Water Board must pump out water from 60 inches of annual rainfall. It advertises a pumping capacity of more than 29 billion gallons a day with a flow rate of more than 45,000 cubic feet per second. It still, however, struggles to pump out water during heavy storms. Moreover, neighborhoods built on the drained swamp continue to suffer from the effects of subsidence, evident in potholes, cracked sidewalks, and damage to building foundations. Finally, removing water from the swamp also increased the area’s risk of catastrophic flooding.

Hurricane Katrina struck in August 2005. Breached levees unleashed a torrent that flipped cars, uprooted trees, and inundated homes across New Orleans. Water eventually covered eighty percent of the city. Flooding was deepest in neighborhoods built on drained swamp. Most areas on high ground escaped serious damage. Since the storm, residents have become increasingly aware of the divisions between neighborhoods above sea level and neighborhoods below sea level. High ground has become a hot commodity; many neighborhoods that remained dry during Katrina are now facing increasing gentrification. Meanwhile, people rebuilding in low-lying areas have seen their property values fall at the same time as their flood insurance rates double or even triple. Topography, more than ever, has become a source of inequality, reshaping perceptions of both economic value and environmental risk.

A new paradigm for water management

In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, a number of bureaucrats, environmentalists, and urban planners have begun to explore new approaches to water management in the hope of stemming subsidence and preventing future catastrophes. Many now recognize that Hurricane Katrina wasn’t a natural disaster, but was the product of urban development and environmental engineering, and tied to a distinct approach to water management.

The Urban Water Plan hopes to move beyond the “pumps and pipes” paradigm to incorporate water into the built space of the city. It proposes creating rain gardens and open canals as well as changing zoning laws and building codes. Still, the authors do not merely seek technocratic solutions. As the phrase “living with water” suggests, there is a philosophical tinge to these projects. Water management projects reshape subjectivity and citizenship as they encourages residents to cultivate new environmental attitudes and practices.

Of course, the plan is not without its critics. Some see it as too ambitious, while others see it as a way of “putting the cart before the horse,” especially in neighborhoods still trying to recover following Katrina. At a public presentation on the plan, one resident stood up and said, “Bring our people back before you bring the water back.” Activists worry about the plan’s silence on race and class issues, or the potential for displacement. Yet the plan raises important questions about water management in a city that faces increasing risks from climate change. Policymakers and planners around the world look to New Orleans for lessons in managing water, whether from superstorms or from rising sea levels. The recent flooding in Baton Rouge shows that it doesn’t take a hurricane to cause a catastrophe. As experts raise questions about the future of many coastal cities, it might be useful to pay attention to how New Orleans confronts its own water challenges, and the new urban ecologies that result.

In the next post, Shreya Subramani will explore some of the questions that have emerged as city officials translate plan into practice.

Endnotes

[1] Quoted in Campanella (2008, 81).

[2] About $650,000,000.00 in 2016 dollars.

[3] Most of these pumps are still in use today. One of the challenges facing the city is the enormous cost of maintaining or replacing this century-old infrastructure.

[4] See Peirce Lewis (2003, 67).

References

Campanella, Richard. 2008. Bienville’s Dilemma: A Historical Geography of New Orleans. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Lewis, Peirce. 2002. New Orleans: The Making of an Urban Landscape. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Waggonner & Ball Architects. 2013. Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan.

1 Trackback