On June 18, 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced the removal of “transsexuality” (a term based on psychiatric diagnosis and maligned by many trans activists as pathologizing) from the “mental disorders” section of its International Classification of Diseases (ICD). After decades of activism, this move was applauded by trans activists around the world. Nonetheless, activists insist that the WHO—rather than removing trans identities entirely—should included them instead in its list of “sexual health conditions.” The commercialization of healthcare in much of the world means that, while trans people have no desire to be classified as “sick” or “mentally ill,” an official medical diagnosis remains crucial for accessing affordable medical care during the process of physical transition (to cover things like hormone therapies, surgeries, mental health support costs, etc.). In countries such as the US, where even private insurance companies are famously reticent to cover any expense not deemed “medically necessary,” the complete removal of trans identities from health manuals such as the ICD would risk depriving these same people of access to the treatments they need. As such, many trans activists view this fraught relationship with medical science as, for the moment, a necessary evil in the fight for full depathologization of trans identities.

In Chile, where trans activists have spent the last decade fighting for basic recognition under the law, the removal of trans identities from the ICD was welcome news to received in June, the world LGBTQIA pride month. The WHO’s decision comes at a time when Chile’s proposed Gender Identity Law—which has now spent 5 years being batted around Congress—is poised to finally pass, despite the recent election of right-wing President Sebastián Piñera with major evangelical backing.

Flipping the Script

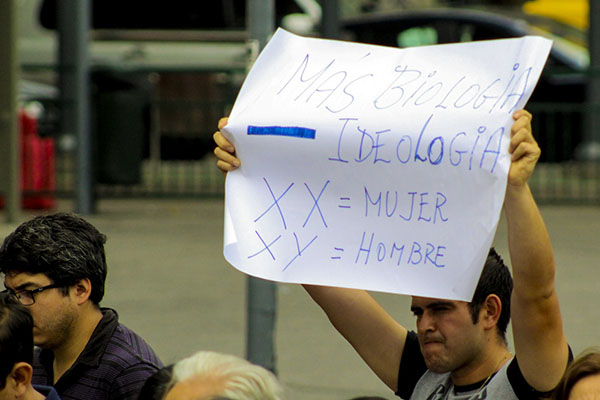

The WHO’s decision is perhaps most important in the court of public opinion. As Chile’s Gender Identity Law comes ever closer to passing, the battle over trans rights—especially as they apply to children—has increasingly become a battle between scientific authority and that of personal emotions and lived experience. Historically, activists on both sides of the issue have, at various moments, employed the language of science to defend their respective postures. Trans activists have argued that people are born trans, while anti-trans voices argue that chromosomes determine our identities, and that it is the so-called “ideología de género” (literally “gender ideology,” a catch-all term comparable to the “radical gay agenda”) that convinces children to be trans. What is perhaps most surprising is that scientific arguments against including children and teenagers in the proposed legislation often come from Evangelical Christians, a group which, in both Chile and the US, has historically not relied on scientific evidence for advancing its agenda. While Chile remains a majority Catholic country, Evangelicals have made significant inroads there and throughout Latin America, often bringing with them the political agendas of their US-based churches, including anti-LGBTQIA stances, opposition to abortion and birth control, and rejection of the scientific consensus on topics like climate change and evolution.

Over the last year, however, during the most intense period of recent debate over the bill in the Chilean legislature, anti-trans activists have increasingly allied themselves with select members of the medical and scientific communities to plead their case. Having gained key political support from members of Chile’s right-wing parties—most notably Pía Adriasola, the wife of former far-right congressman, José Antonio Kast—these activists have gained access to both closed and public sessions, often being allowed to speak before, or in the place of, representatives from Chile’s trans rights organizations. In one such case Francisca Ugarte, a pediatrician and endocrinologist invited by anti-trans activists, suggested that the actual trans population could be as low as 1 in 5 million people. This figure suggests that Chile’s total trans population is between 3 and 4 people in the entire country, a laughable assertion—there were at least 10 trans people in the room at the time—that nonetheless has real-world consequences.

Academic titles are highly respected in Chile. As such, it is not surprising that Dr. Ugarte’s credentials allowed her to present obviously false data as fact before Congress. Other anti-trans activists have cited universally panned studies that suffer from obvious methodological flaws, ranging from the inclusion of children exhibiting “subthreshold” gender noncomforming behaviors in a supposedly trans-specific sample (Drummond, Bradley, Peterson-Badali, & Zucker, 2008) to the use of children who left the study (roughly half the sample) as evidence of children “desisting” from gender transition (Steensma, Biemond, de Boer, & Cohen-Kettenis, 2011). For a more detailed analysis of these studies, click here. These same experts ignore the wealth of evidence showing the benefits of early support of a child’s gender identity, demonstrating the malleability of the scientific method, despite its claims of objectivity (Durwood, McLaughlin, & Olson, 2017). However, this recent interest in scientific discourse is a relatively recent occurrence among Chilean anti-trans activists.

The “Freedom Bus,” brought to Chile by anti-trans activists in July 2017, eschewed scientific argumentation in favor of an appeal to parental emotion. Less than a year later, however, these forces have adopted the language of science to advance their agenda.

From Emotion to Science

In July 2017, one such anti-trans activist, Marcela Aranda, also the mother of a trans child, brought the “Bus de la Libertad” (Freedom Bus)—which had previously visited several European cities—to the streets of Santiago. The bright orange bus, reading “#ConMisHijosNoSeMetan” (#Don’tTouchMyKids) and “Nicolás tiene derecho a un papá y una mamá” (Nicolás has the right to a father and a mother), made reference to the children’s book “Nicolás tiene dos papás” (Nicolás Has Two Dads), published by LGBTQIA rights group Movilh. In contrast to the European version of the bus, which contained slogans arguing that “Men have penises, women have vaginas” and “We are born XX or XY,” Aranda’s version of the bus made no mention of science, appealing instead to the emotions of her base, and ignoring the difference between gender identity and sexual orientation. Aranda clearly hoped to generate an emotional response with her publicity stunt. Nonetheless, less than one year later, it is these same anti-trans forces in Chile who stand before Congress arguing the scientific basis of biological sex (dismissing myriad intersex identities as “outliers”) while pro-trans forces make emotional arguments for the rights of children to define their own identities, regardless of what medical and psychiatric professionals say.

An Evangelical protester holds a sign reading “More biology, less ideology. XX = Woman, XY = Man” at an anti-trans rally in January 2018. Photo by the author.

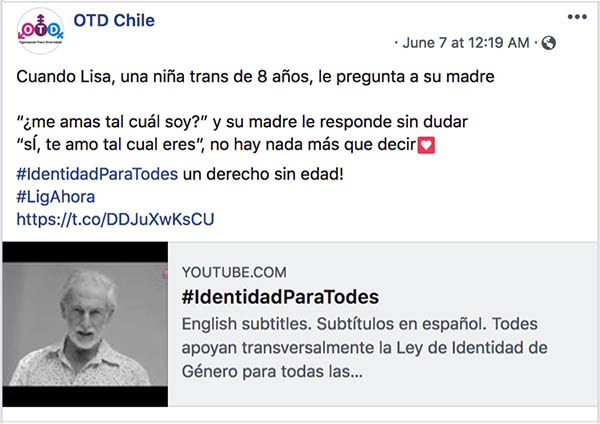

Curiously, as anti-trans forces have increasingly turned to questionable scientific evidence to plead their case before Congress, trans organizations have taken the opposite tack. While trans activists in Chile have by no means abandoned the “born this way” rhetoric prevalent in the global LGBTQIA movement for the last decade, they increasingly also appeal to other forms of argumentation. Organizations like OTD Chile and Fundación Selenna have recently adopted a right-based approach, eschewing the question of nature vs. nurture in favor of the “right to identity,” enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, of which Chile is a signatory.

[Translation] When Lisa, an 8 year old trans girl, asked her mother “Do you love me just the way I am? and her mother responded without question “Yes, I love you just the way you are,” there nothing more to say. #IdentityForEveryone, a right that knows no age!

A Memorable Day

As I began to write this post, the “Comisión Mixta” (Mixed Commission)—a committee made up of Senators and Deputies charged with adjusting the current version of the law to obtain multi-partisan support—agreed to incorporate children into the language of the proposed legislation, albeit with caveats. This will undoubtedly fan the flames of the conservative anti-trans movement, who had dissipated somewhat after the removal of children from the law some months back. It remains to be seen what impact the WHO’s decision will have on Chile’s trans rights movement. On one hand, the depathologization of trans identities remains a primary goal for trans activists both in Chile and around the world. On the other hand, as trans activists move away from science-based argumentation, and as their opponents embrace it, it is unclear how strategies on both sides of the aisle may change. While trans activists have certainly celebrated the WHO’s decision, they—along with most of the scientific community—have long known that trans identities do not represent a pathology. Their opponents, though, despite having only recently adopted the language of scientific authority, may soon once again have to rethink their strategy as global scientific consensus and popular opinion shifts away from their ideals.

With or without the support of the scientific community, trans people—and trans children—exist, and it is incumbent on world governments to guarantee their rights and freedoms; the recognition of medical and scientific authorities is but one crucial step toward this goal. Though the struggle for trans depathologization continues, Débora Fernández, a Chilean trans activist, summed up the immediate importance of the WHO’s decision in her Facebook post.

![A Facebook post reads, in translation: [Translation] What a memorable day, my wish has come true: We trans people are no longer lumped under the category of mental illness by the WHO, in Argentina the murderer of Diana Sacayan was sentences (thanks to the long struggle of multiple organizations), with the court having recognized travesticide as a crime, and in Chile the Mixed Commission approved the inclusion of teens and children in the Gender Identity Law (another historic struggle of multiple organizations and activists.)](http://blog.castac.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2018/06/2020sz-debora-post.jpg)

[Translation] What a memorable day, my wish has come true: We trans people are no longer lumped under the category of mental illness by the WHO, in Argentina the murderer of Diana Sacayan was sentences (thanks to the long struggle of multiple organizations), with the court having recognized travesticide as a crime, and in Chile the Mixed Commission approved the inclusion of teens and children in the Gender Identity Law (another historic struggle of multiple organizations and activists.)

References

Drummond, K. D., Bradley, S. J., Peterson-Badali, M., & Zucker, K. J. (2008). A Follow-Up Study of Girls With Gender Identity Disorder. Developmental Psychology., 44(1), 34.

Durwood, L., McLaughlin, K. A., & Olson, K. R. (2017). Mental Health and Self-Worth in Socially Transitioned Transgender Youth. JAAC Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(2), 116–123.

Steensma, T. D., Biemond, R., de Boer, F., & Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. (2011). Desisting and persisting gender dysphoria after childhood: A qualitative follow-up study. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 16(4), 499–516.

1 Comment

In countries with solely tax funded medicine do they provide services for conditions not in the ICD?

2 Trackbacks