Image courtesy of the author.

This essay is a collage of images and writing from an ongoing project “Reading the River: Yemayá and Oshun.” I am approaching it as an experimental documentary that looks at the relationship between Blackness and the Mississippi River as a collision of ideas, cultural practices, political geographies, and intimacies. This manner of working emerges out of a Black feminist practice of unsettling how we think and know place.

—Tia-Simone Gardner

S S M – I – CROOKED LETTER CROOKED LETTER – I S S CROOKED LETTER CROOKED LETTER – I P P HUMPBACK – HUMPBACK – I

Mississippi, or THE Mississippi,

is a body memory. The Black

Body and Mississippi stick to

one another, in pleasure and

in violence, through metastasis

and re-membering.

“The natural levee along the Mississippi River is a mass

grave, filled with the city’s earliest workers and slaves.” [1]

when I was a child, we had a chant.

we learned to spell

M I S S I S S I P P I

by singing the letters aloud, clap-

ping our hands in time, and hunching our

shoulders up to our ears. It is a useful

chant; it helped us to also keep time as

a song to jump rope.

M – I – CROOKED LETTER CROOKED LETTER – I CROOKED LETTER CROOKED LETTER – I HUMPBACK – HUMPBACK – I

…I’m still not sure if we were singing about the

land or the water.

…they are not always so distinct, the land and the water.

Image courtesy of NASA.

…perhaps it was both.

Neither are the land, water, and body completely distinct.

Like land and water, the Black body was remapped. Rearticulated through a range of regimes: racial capitalism, colonization, labor exploitation, into a site of extraction. The Black body was, is, undifferentiated from the land and water that are habitually used to make life, for some, more livable.

“…we must now consider the roads, rivers, and showrooms where broad trends and abstract totalities thickened into human shape.” [2]

Moved, overworked, defiled abstracted as an object of trade, the Black body is an important feature, like the pot ash tree or the bald cypress of the Southern landscape. And the river is a part of this strange abstraction.

“In the seven decades between the Constitution and the Civil War, approximately one million enslaved people were relocated from the upper South according to the dictates of the slave- holders’ economy, two thirds of these through a pattern of commerce that soon became institutionalized as the domestic slave trade…

As those people passed through the trade, representing something close to half a billion dollars in property, they spread wealth wherever they went.” [3]

“I was soon inside, cowering with fear in the darkness, magni-

fying every noise and every passing wind, until my imagina-

tion had almost converted the little cottage into a boat, and

I was steaming down South, away from my mother, as fast as I

could go.” [4]

“What the New Orleans slave pens sold to

these slaveholders was not just field hands

and household help but their own stake in

the commercial and social aspirations of the

expanding Southwest, aspirations that were

embodied in the thousands of black men,

women, and children every season: the slaves

out of whom the antebellum South was built.” [5]

…it is both an old and a new acquaintance. When I lived in the South, I knew

it by one name, but it was too far away to enter into my sense of place.

Living now in a place where I am never more than few miles from its banks, its

presence cannot help but be a part of my everyday life.

Now, I also know that it has many names:

Báhat Sássin – (Hasí:nay [Caddo]), “Mother of rivers”

Beesniicíe – (Hinónoʼeitíít [Arapaho])

Hahcicobá – (Kowassá:ti [Koasati])

Ȟaȟáwakpa – (Lakȟótiyapi [Lakota]),“River of the falls”

Kickaátit – (Paári [Pawnee])

Mäse’sibowi – (Meshkwahkihaki [Fox-Sauk])

Ma’xeé’ome’tää’e – (Tsėhésenėstsestȯtse [Cheyenne]), “Big, greasy river”

Mihcisiipiiwi – (Myaamia [Miami-Illinois])

Misi-Ziibi – (Anishinaabemowin [Ojibwe]), “Great river”

Misha Sipokni – (Chahta’ [Choctaw]), “Beyond age”

ᎻᏏᏏᏡᎤᏪᏴ – (ᏣᎳᎩ [Cherokee]) “Mississippi [transliteration] river”

Mníšošethąka – (Dakȟótiyapi [Dakota])

Ny-tonks – (Okáxpa íe [Quapaw]), “Great river”

Ohnawiiò:ke – (Kanien’kéha’ [Mohawk])

Uhtawiyú?kye – (Ska:rù:rę’ [Tuscarora])

Yandawezue – (Waⁿdat [Wyandot])

Yununu’a – (yUdjEha [Yuchi]), “Great river”

Xósáu – (Cáuijògà [Kiowa]), “Standing Rocks” [6]

“pointe ouski” = “cane point”

“bayuk loosa” = “bayou black”

“bayuk ouski” =” bayou cane”

from the Houma language [7]

“water of mars” = war water [8]

“What they gone do with all this property? What the oil company gone do?” [9]

Fort Cities. Port Cities.

Colonization, Spanish, French, British,

American, still marks the landscape

and our bodies.

St. Paul

Cairo

St. Louis

Memphis

Natchez

Vicksburg

New Orleans—

The militarized and commodified rivers-

cape flows from Minnesota to the Gulf and

our bodies flow with it.

Image courtesy of the author.

New Orleans was the largest and perhaps the most feared of the slave port cities along the Mississippi, no one wanted to be sold down river to New Orleans.

Ports and forts tell stories about mobility, Black death and Black life. The commodified Black body. Commodified landscapes and bodies of water. They do not perhaps look like the castles and forts of Elmina or Gorée, but the ports and the forts are there.

Aerial view of the Mississippi River near Fort Jackson circa 1935. Image courtesy of United States Department of Interior, National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places.

Aerial view of the Mississippi River near Fort Jackson circa 1974. Image courtesy of United States Army Corps of Engineers.

Near the confluence of the Missouri and the Mississippi sits Fort Belle Fontaine, the first established American military fort, which predates the Louisiana Purchase. It was once a fur trading post. Now deaccessioned, it lives down the road from a juvenile detention center.

So I ask: what do histories and cartographies that trace and

locate Black mobility along a river that moves between the

Gulf of Mexico and Minnesota reveal about the lives and

struggles of Black populations contemporarily in and

between these spaces?

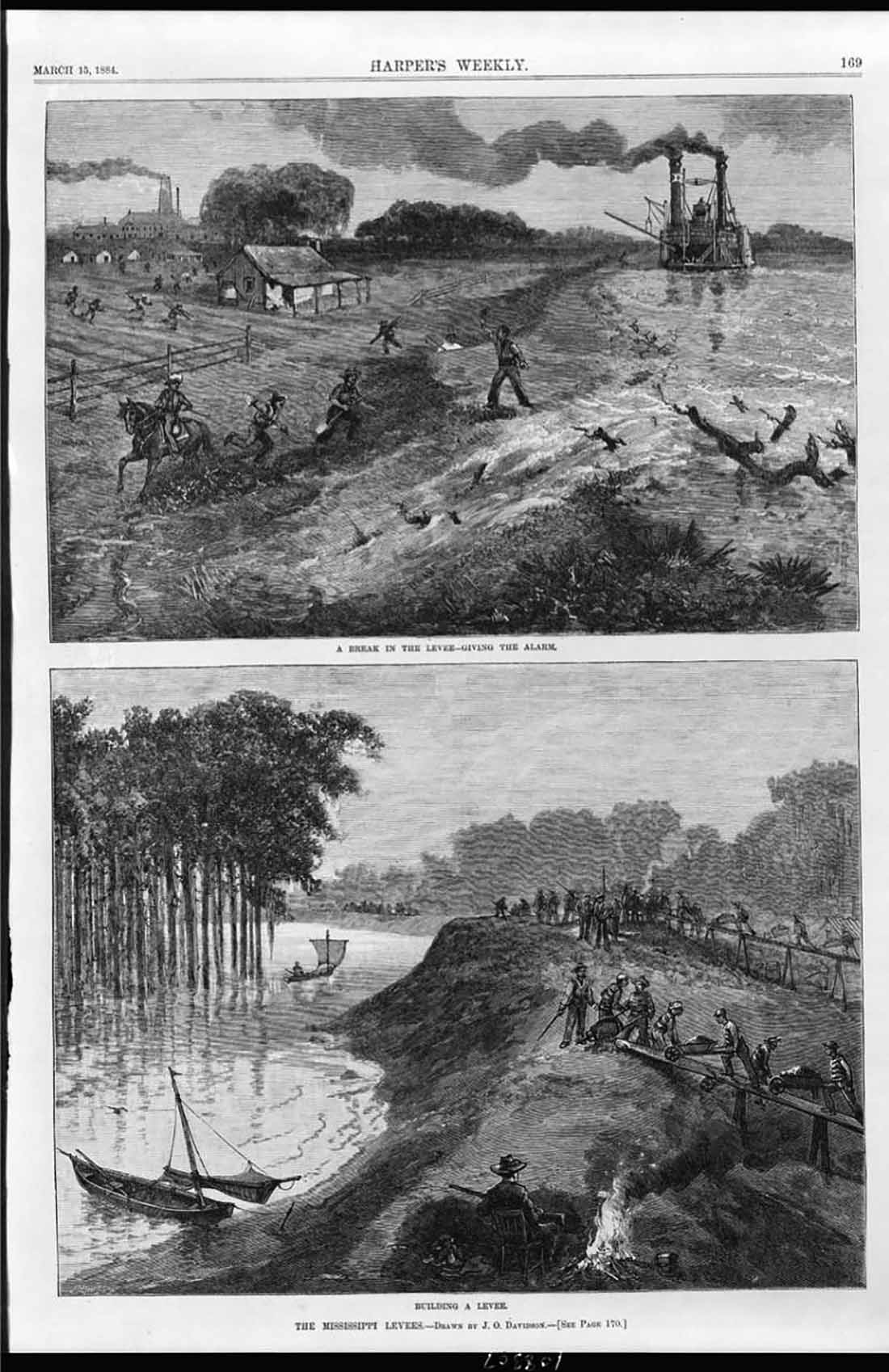

“Harper’s Weekly”, March 15, 1884, 169.

Image courtesy of the author.

he says…the levee took the place of the

Sugar House. They had to move the houses to

place the levee. [10]

Image courtesy of the author.

Ochún…?

Image courtesy of the author.

“Yemayá

I come to you, Yemayá,

Ocean mother, sister of the fishes.

I stop at the edge of your lip

Where you exhale your breath on the

beach

Into a million tiny geysers.

With your white froth I anoint my brow

and cheeks,

Wait for your white-veined breasts to

wash through me… [11]

I stare at the sea, surging silver-plated

between me and the lopped-off corrugated

arm, the wind whipping my hair. I look

down, my head and shoulders, a shadow on

the sea. Yemayá pours strings

of light over my dull jade, flickering

body, bubbles pop out of my ears. I

feel the tension easing and, for the first

time in months, the litany of work

yet to do, of deadlines, that sings

incessantly in my head, blows away with

the wind.

Oh, Yemayá, I shall speak the words

you lap against the pier.

But as I turn away I see in the distance,

a ship’s fin fast approaching. I see

fish heads lying listless in the sun,

smell the stench of pollution in the waters.” [12]

“Because of its qualities as a tan-

gile, visible scene/seen, it follows

that not only can we interrogate the

historical and geographical dimen-

sions of the landscape as an object in

and of itself (as a material thing, or

set of things), we also can read and

interpret cultural landscapes for

what they might tell us more broadly

about social worlds of the past.” [13]

“…rather than seeing surveillance

as something inaugurated by new

technologies, such as automated fa-

cial recognition or unmanned auton-

omous vehicles (or drones), to see it

as ongoing is to insist that we fac-

tor in how racism and antiblackness

undergird and sustain intersecting

surveillance of our present order.” [14]

Image courtesy of the author.

…the Police-like people I encountered

on the levee were ICE agents, Immigra-

tion and Customs Enforcement.

They might have taken my camera and

what I thought were harmless images of

the ships in the channel.

I wonder what, or who, is aboard the

ships? Would it, they, have to be quar-

antined? How did ICE determine the

border in the river?

…do borders float? Not all people do.

Image courtesy of the author.

Footnotes

[1] Rich, Nathaniel. 2013. “Bodies.” In Unfathomable City: A New Orleans Atlas. Rebecca Solnit and Rebecca Snedeker, eds. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

[2] Johnson, Walter. 1999. Soul by Soul : Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 8.

[3] Johnson, Walter. 1999. Soul by Soul : Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 6.

[4] Delaney, Lucy A. 189-?. “From the Darkness Cometh the Light, or Struggles for Freedom.” In From the Darkness Cometh the Light, or Struggles for Freedom. St. Louis, MO, Publishing House of J. T. Smith II.

[5] Johnson, Walter. 1999. Soul by Soul : Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 7.

[6] “Native Names for the Mississisippi River” in The Decolonial Atlas. January 5, 2015.

[7] Verdin, Monique. 2013. “Southward into Vanishing Lands.” In Unfathomable City: A New Orleans Atlas. Rebecca Solnit and Rebecca Snedeker, eds. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

[8] Hurston, Zora Neale, and Miguel Covarrubias. 1935. Mules and Men. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co.

[9] Dent, Thomas. Thomas Dent Papers. Amistad Research Center at Tulane University.

[10] White, Frank. “River Road Interviews.” Thomas Dent Papers. Amistad Research Collection at Tulane University.

[11] Anzaldúa, Gloria. 2009. The Gloria Anzaldúa Reader. Latin America Otherwise. AnaLouise Keating, ed. Durham: Duke University Press. 242.

[12] Anzaldúa, Gloria. 2009. The Gloria Anzaldúa Reader. Latin America Otherwise. AnaLouise Keating, ed. Durham: Duke University Press. 114.

[13] Schein, Richard H. 2006. Landscape and Race in the United States. New York: Routledge, 5.

[14] Browne, Simone. 2015. Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness. Durham: Duke University Press. 8.

Editor’s note: This essay was originally published in Open Rivers: Rethinking Water, Place, and Community.