When I would tell people I worked in the small San Francisco Bay Area suburb of Emeryville, they would almost always say, “Emeryville is weird.” And then the conversation would usually stop there, they couldn’t put their finger on quite what they meant. But there’s a strangeness that hangs over the city that everyone feels, and no one can quite describe.

Emeryville is mostly made up of tech campuses – the occasion for my fieldwork – and new condos, big box stores and biotech and software companies, along with some bars and restaurants for people on their breaks, and that’s nearly it, because the whole city is one square mile. Emeryville is busy during the day with professionals, who never stay more than a drink or two after work, and the place is mostly cleared out by night. It has a too new kind of feeling where all the buildings are made out of the same kind of glass and the trees are little and twiggy and still need plastic ribbons to prop them.

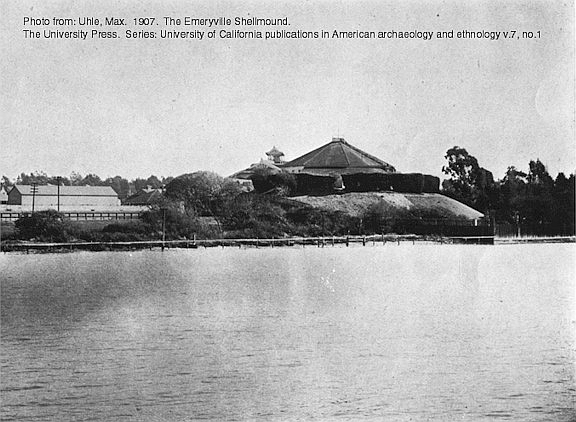

By Alax Uhle 1907 The Emeryville Shellmound. University of California Publications American Archaeology and Ethnology, vol. 7, no. 1, Plate 2, Wikimedia Commons

It’s a city often read by its neighbors as an empty receptacle for tech companies, malls, and other institutions of neoliberal capital. It’s what Marc Augé called a “nonplace,” the kind of place defined by its absence, meant to move people and money through interchangeably: shopping malls, airports, parking lots, business parks (Augé 2008). Emeryville is the exemplary nonplace, but it’s also not a nonplace at all because so many people need to remark on its weirdness even if they don’t know what to say beyond that. Or they only have a half-articulated explanation – “I bike through it sometimes and it’s weird. Its size is weird.” Or “No one really lives there,” or, “The whole city is an IKEA parking lot.” Or “Did you know the town used to be a dump?”

There’s information even in these fleeting impressions of something off-key: the city’s size, its IKEA, trashscapes in the surprisingly recent past. These are points with interconnections that prompt the feeling of strangeness within the otherwise unremarkable. Follow the points far enough, and they appear as intuitions of deeper histories and political dynamics — dynamics and histories that might give us more information about what we’re not thinking about when we think about nonplaces, or even places for that matter, in North Atlantic modernity.

For example, Emeryville’s size: the city is a jaggedy, one-mile strip that borders Oakland with no obvious relationship to any natural features. The result is most movement through Emeryville is experienced as a tiny sliver in front of the bay shore; or as five minutes in the car before you hit Berkeley; or as a gentle walk through manicured business parks that suddenly hits Oakland’s San Pablo Avenue, with speeding traffic, aging storefronts, and many more unhoused people on the sidewalk.

As it turns out, these abrasive transitions are part of the city’s origin story. Neighboring Oakland became an official city in the late 1800s and began annexing nearby land, and Emeryville is so small it would have made sense for the unincorporated area to become a neighborhood in Oakland. But it incorporated into its own city, what contemporaries read as a strategic move by local property owners to retain control over the flourishing chemical industries, gambling dens, and saloons that an Oakland city government might not be so amenable to (Perrigan 2009).

Most of this industry moved out in the postwar period, and not much moved in for several decades because of the toxic messes unrestrained capitalism left behind. But the totalizing contamination of the city became its own windfall, because of the way 95% of Emeryville’s land fell into a redevelopment zone. Redevelopment policies authorized an unusual amount of leeway to offer tax breaks, subsidies, eminent domain for commercial rather than public interests, and other sweetheart deals meant to bring developers in to clean up and build out derelict, industrial plots of land. Emeryville’s city council wielded this effectively enough to rebuild the half-vacant city with retail outlets and tech by the end of the 20th century.

But as local activists have argued, “to some extent, Emeryville did well at the expense of its neighbors” (Goll 2003). Private firms benefitted from public resources oriented toward building economic growth, and the economic boom was executed partly through the construction of low-wage service jobs for workers who ultimately rely on public housing in neighboring Oakland, Richmond, and Berkeley.[1] The redevelopment ultimately benefited luxury retail over essential services, Pixar’s luxurious fenced-in campus over public park space, and gentrifying newcomers over the gradually displaced historic low-income residents (Greenwich and Hinckle 2003). These allocations of public resources were more possible because of the ways the city remains embedded in a metropolis of other cities available to pick up the slack. Which is to say, the city’s unusually small size and gerrymandered border aren’t just quirks of the city, but key to its liberal, then neoliberal manipulations of geographic space.

These are felt at the level of a bike ride through the city that seems a little off – or in the irritation expressed on the East Bay Local Wiki page for Emeryville at local residents who constantly narrate local crime as “on the border with Oakland,” when the city is so small that “everywhere is the border with Oakland” (Localwiki 2014). Emeryville can be tech-friendly in part through its borders, which attract business in with tax increment financing and keep others out with police. So much is explicit in a local newspaper’s interview with council member Nora Davis, who helped oversee the renewal period to guide Emeryville. She expressed her skepticism about the virtues of the “vibrant” city and said instead she strived to build the kind of city where “you call the cops, you got a cop on your door in five minutes. Unlike across the street, in one of our neighboring cities…” (Arias 2015). The apparent sterility of nonplaces is constructed through very literal material forces, like police, and part of Emeryville’s weirdness is how the other side constantly leaks through a boundary so artificially and delicately held.

Because while you may be able to get a cop on your doorstep faster than you can in Oakland, Emeryville still has the highest property crime rate of any small city in the entire United States (Rehman 2021). The policed border makes the world of Pixar campuses possible, and the hundreds of thousands of dollars spent on reagents every week at local biotech companies, but in such a way where the other side is always leaking through, to jarring effect.

Maybe the most leaking of all happens at the ever-controversial Bay Street Shopping Plaza, most Bay Area residents’ only direct encounter with Emeryville. What most people who visit the mall don’t know, but enough do, is that it covers over what was once the biggest shellmound in the world. The Bay was once ringed with shellmounds, massive burial sites of generations of indigenous Ohlone people. Emeryville’s shellmound survived settler colonialism longer than most, until 1920 when it was leveled to make way for a paint factory. The factory was eventually abandoned in the city’s deindustrialization, until developer Madison Marquette began an environmental remediation process in 2000 to remove the dangerously high levels of lead and arsenic in the ground to build a shopping plaza. In the process, it became public knowledge that there were still bodies underground. After public protests and legal pursuits for indigenous land reclamation, or at least a return of the remains, the estimated hundreds of bodies still under the surface were paved over or else sent to an incinerator because they were too saturated with toxic paint.

The one concession required of the mall’s developer, Madison Marquette, was a memorial to the shellmound on the mall’s grounds. It’s confusing to encounter this memorial with no context – a nice fountain coming out of a grassy knoll next to a series of stones engraved with a misleading history of indigenous people in the area. There are facts about shellmounds, mostly described as piles of waste, and about Ohlone, described entirely in the past tense. You would have no idea why this small outdoor museum was built behind P.F. Chang’s and hidden from most of the rest of the mall. Probably because there’s no reasonable way for a mall to commemorate something it helped destroy. But the memorial still does work in the world, radiating a vague sense of something only half acknowledged and something else avoided.

Aside from confusing stray shoppers, the memorial has also been co-opted by the local indigenous land-back organization, Sogorea Te’ Land Trust, into the site of a now twenty-year running Black Friday protest. Andrés Cediel’s documentary captures one of the events where protestors hand shoppers maps marking the locations of bodies under the mall (Cediel 2005). Some of the shoppers respect the boycott and leave, more of them become defensive or hostile, but all are made aware of the ground they stand on.

The Bay Street Shopping Plaza was also one of major sites of property damage in the Bay Area during the 2020 summer uprisings in the wake of the murder of George Floyd. As a local news organization reported the social media response: “Some of the most retweeted comments pointed out Emeryville’s 1924 Ohlone Shellmound destruction, our city’s affinity for ‘big box’ retail and willful participation in capitalism as justification for this looting. That this was a form of ‘reckoning’ for Emeryville’s past and current sins.” (Arias 2020). The damages in combination with the nation-wide decline in the brick-and-mortar shopping mall, accelerated by the pandemic, have progressively emptied the plaza, with a vacancy rate now teetering on the cusp of a ghost mall.

A part of Emeryville’s weirdness is places like these where the steam leaks through, where the too new crumbles back into something very old. It’s a kind of temporality Christina Sharpe’s notion of residence time helps to reinterpret. A term borrowed from fluid dynamics, residence time draws attention to the material presence of death, specifically, the bodies of enslaved people thrown overboard in the Middle Passage which remain four hundred years later as atoms in the ocean (Sharpe 2016). A nonplace is created through an act of leveling, of covering over a former place, but erasure is only possible in a strictly modernist imagination. A mall is built on the concrete that permits a nonplace, but something else remains beneath the concrete, at the level of local knowledge, or a weird feeling, and even in the most literal physical sense.

The act of leveling isn’t so much an erasure as it is an action with material effects. A burial site becomes a different thing in the world when it is so saturated with toxic paint that the human bones have turned the color orange and the texture of rubber. A desecrated sacred site is biochemically different than a revered one. The difference amounts, in this case, to a corporate fountain where people convene for twenty years to pass out maps of the bodies underground and instigate forms of resistance that may prove to eventually kill the mall. The place never leaves the nonplace, not only because old histories live on, but because the very act of leveling continues to build on the legacy it seeks to destroy.

Notes

[1] Greenwich and Hinkle point out that the city’s redevelopment has included the construction of affordable housing, but ultimately it also constructed four times as many low-wage jobs requiring subsidized housing as it did housing units for these workers.

Acknowledgments

This essay was initially written as part of a collection on the “No-Place” with Taylor Genovese, Schuyler Marquez, Heather Mellquist Lehto, and Gaymon Bennett. We were sadly unable to find a home for the unusual format and have since broken our essays into individually authored units. But our writing together was foundational to the conceptual points made in this paper, as was substantial and invaluable feedback from my co-authors.

This research was conducted with support from the Collaboratory on Religion, Science and Technology in Public Life at Arizona State University’s Center for the Study of Religion and Conflict. An additional thank you to Charlie McCrary and Jennifer Clifton, in our Digital Culture workgroup in the CoLab, who also provided support and critique.

References

Arias, Rob. 2015. “An Exclusive Conversation with 27 Year Councilperson Nora Davis.” The E’ville Eye Community News (blog). March 13, 2015. https://evilleeye.com/news-commentary/politics/exclusive-conversation-26-year-councilperson-nora-davis/.

———. 2020. “‘Frustration, Disappointment, Disgust’ Emeryville Community Reacts to City’s May 30 Looting.” The E’ville Eye Community News (blog). July 2, 2020. https://evilleeye.com/news-commentary/frustration-disappointment-disgust-emeryville- community-reacts-to-citys-may-30-looting/.

Augé, Marc. 2008. Non-Places: An Introduction to Supermodernity. 2nd English language ed. London: Verso.

Cediel, Andrés. 2005. Shellmound. Berkeley, Calif.: UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism.

“Emeryville.” 2014. Oakland – LocalWiki. October 7 https://localwiki.org/oakland/Emeryville.

Greenwich, Howard, and Elizabeth Hinckle. 2003. “Behind the Boomtown: Growth and Urban Redevelopment in Emeryville.” Oakland, California: California Partnership for Working Families, https://workingeastbay.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Behind-the-Boomtown-Report.pdf.

Perrigan, Dana. 2009. “Emeryville’s Transformation.” San Francisco Chronicle, June 21. https://www.sfgate.com/realestate/article/Emeryville-s-transformation-3228026.php.

Sharpe, Christina Elizabeth. 2016. In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Durham: Duke University Press.

1 Comment

I am trying to understand why you would refer to the native tribe, the Ohlone people “co-opted by the local indigenous land-back organization, Sogorea Te’ Land Trust, into the site of a now twenty-year running Black Friday protest.” They are educating the public that the mall is built on the bones and remains of their ancestors. And for the people who can connect with that atrocity and understand what that feels like, this education is necessary.