“I am not reading all of that, but fuck Chu May Paing. What a fraud.”

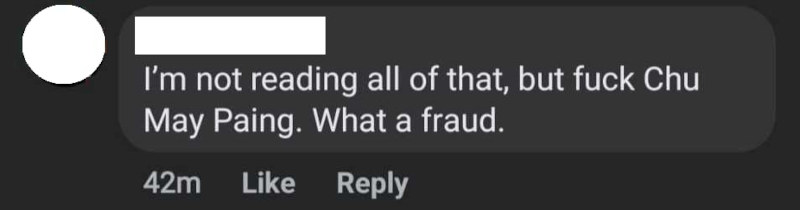

I didn’t see the comment on Facebook when it was first posted. I only found out a day after, through a friend of mine who shared a screenshot of the comment with me over a direct message. I will refer to the troll by a generic pseudonym of “John.” As ballsy of a troll as he was to leave such an inflammatory comment about me using his full real name, John was still not brave enough to leave it directly under one of my posts; he had left it under someone else’s post who mentioned my writing. I recognized John’s name right away when I saw the screenshot. John is a cishet white man in his late 30s or early 40s doing a PhD in anthropology with a focus on my home country Burma at an institution located on the Pacific Coast of the United States. As a frequent writer of irritating comments on Burmese users’ posts that create unnecessary disruptions in online discussions of Burma, John is notorious as an annoying online troll. He might be better known as a troll than a “scholar.”[1] The Internet is John’s playground. Burmese people are his target. And trolling on Facebook seems to be how he soothes his boredom.

The above comment, left in English, contributed nothing to the digital conversation unfolding in Burmese between me and the fellow Burmese person who wrote the original post. It was simply another one of his attempts at trolling Burmese people, and local and native scholars and activists. And as a first generation Burmese immigrant femme who recently completed a PhD in anthropology, I just happened to fall within John’s radar. So, how are we supposed to deal with trolls like John? What is the social function of trolling and in what context can trolling be an empowering act for those of us who are already systematically marginalized? What are the ways in which we could reduce online harm and harassment like this incident?

Figure 1. Screenshot of John’s trolling comment left under a Burmese-language post engaging with one of my Burmese-language essays, shared with me by a Burmese friend through direct messaging. Retrieved on June 29, 2024.[2]

Trolls as Agitators

Originating from an initial meaning of a dwarf or a giant that dwells in caves in Scandinavian folklore, the word “troll” in the Internet age has evolved into the action of “antagonizing (others) online by deliberately posting inflammatory, irrelevant, or offensive comments or other disruptive content.” Merriam-Webster dictionary includes among its long list of definitions “to harass, criticize, or antagonize (someone) especially by provocatively disparaging or mocking public statements, postings, or acts.” In the west, trolling has broadly been theorized as anti-social behavior committed by a minority group, out of boredom and sadistic pleasure (Pfattheicher et al 2021), nihilism (Owen et al 2017), or for fun (Backels et al 2014).

For many Burmese, online trolling is not something new; its practice and characteristics resembles a long-standing Burmese tradition of political satire. As I have written elsewhere (Chu May Paing 2020), political satire and satirists use cultural expressions such as theater, cartoon, poetry, literature, and song to poke fun at the oppressive military regimes and power-mongering elites. Most recently, in the aftermath of the 2021 military coup, political satire has resurfaced on social media making use of new digital features such as deep-fakes, memes, and wordplays. They are “deliberate, deceptive and mischievous attempts to provoke reactions from other users,” all of which Maja Golf-Papez and Ekant Veer (2017) identify also as the characteristics of trolling.

A portion of my dissertation on anti-military activism on Burmese social media examines this phenomenon of digital political satire in contemporary Burmese politics. An explicit example can be seen below with a post shared by an account called “နီပေါ Troller” (nepaw Troller) just one day after the military staged the coup on February 2, 2021. Referencing the NLD Party’s theme color, red, the term nepaw or “dumb red” (ne-red, paw-dumb) pokes fun at anyone who blindly follows Aung San Su Kyi and her party. In the post below, nepaw Troller mocks NLD and Aung San Su Kyi followers who changed their Facebook profile pictures to red in support of Aung San Su Kyi: “Hey lovelies, you said you’d vote for [Aung San Su Kyi] even if there’s bombing. But now, even when the leader mama got arrested and the only thing you do is change your profile picture? #oopssaiditagain.”

The euphemism nepaw is cheeky because it can be used both to refer to people who follow Aung San Su Kyi without any questions asked, as well as by leftists dissatisfied with a mainstream politics that still ignores the ongoing Rohingya Genocide, class inequalities, and ethnic and religious discrimination. On the other hand, the military supporters and sympathizers can also easily use the reference for their own pleasure of mocking pro-democracy citizens.

Figure 2. Facebook page “nepaw Troller” shared a post on its page, mocking those who follow Aung San Su Kyi and the NLD Party. The image shows a Burmese traditional Gaung-Paung (cloth headwrap) usually worn by Burmese men in formal attire, and mostly seen worn by male politicians at formal political events. The text above writes, “Troller.” The background color of the image signifies the symbolic red color of the NLD party. Retrieved on September 27, 2023.

Trolling Runs Wild

Trolling is powerful because it playfully agitates those in power and the official narratives while still avoiding punishment. Burmese expressions such as “walking on a person’s eyebrows” (မျက်ခုံးမွှေးစင်္ကြန်လျှောက်), or “as if one is driving a cart full of thorny branches” (ဆူးလှည်းကြီးမောင်းလာသလို), capture the essence of trolling perfectly. One cannot see, but only sense, something on their eyebrows. A cart full of thorny branches scratches every single person on its path. Therefore, the slipperiness and ambiguity of trolling make it hard to accuse the troll of the acts they committed. Another Burmese expression, “in between the fingers” (လက်တစ်လုံးကြား), explains the trolling behavior of switching truth with falsehood and vice versa. All these expressions show a troll’s ability to slip in and out of character at any given moment and its quality to remain ambiguous when confronted.

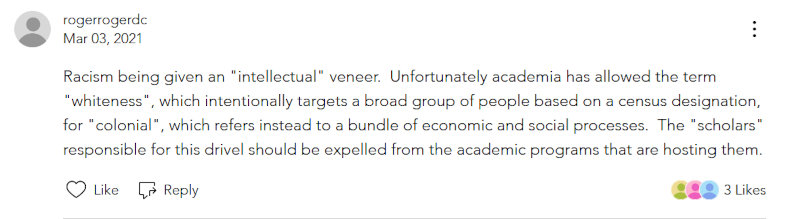

But what happens when political satire and trolling, which have been considered weapons of the weak, are usurped by the powerful elite and misogynistic men? Such tongue-in-cheek trolling makes it harder to monitor, control, and regulate when it comes to online harassment, discrimination, and cyberbullying motivated by alt-right ideologies, racism, sexism, and digital misogynoir (Bailey 2021; Ortiz 2020; Herring et al 2002). As a femme feminist of color writer and scholar, I have had my own share of misogynistic trolls, especially from cishet white men. Some employ identity-based harassment and poke fun at my name, gender, and race; some belittle me by dismissing my writing, and demand my expulsion from academia. Although the trolls I have encountered so far are not yet extreme to the point where they threaten my physical well being, I wonder if there is nothing to be done about the psychological and emotional distress that the trolls inflict. Is there really nothing to be done about the (cishet white male) trolls that harass women, people of color, and marginalized peoples?

Figure 3. A public comment left by an account named “rogerrogerdc” under a blog post containing the video recording of a presentation of my co-authored paper “Talking back to white Burma Experts” at the 20th International Graduate Student Conference held at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa on Feb 12, 2021.[3] The paper won the Outstanding Abstract Award at the conference. Retrieved on June 28, 2024.

Trolling Back as Harm Reduction

The question led me to Dr. KáLyn Coghill’s public teach-in titled “Clappin’ Back: A Look into Digital Misogynoir and Online Harm Reduction Practices,” organized by Black Women Radicals and The School for Black Feminist Politics.[4] In their teach-in, the Digital Director for the MeToo Movement Dr. Kay outlines how Black women and gender non-binary people have long been subjected to and discriminated against by digital misogynoir, “the unique discrimination that Black women and non-binary gender expansive femmes experience in the digital spaces” (Coghill 2024: video timestamp 25:57). In response to dealing with digital misogynoir, Dr. Kay puts forth a theoretical practice of “clappin’ back” as one of the salient online harm reduction strategies (44:18). Clappin’ back is “a witty response or retort, the finding out after fucking around, a rhetorical device to hold folks accountable” (44:24). Instead of staying silent and ignoring, to clap back is to talk back at the trolls. It is a refusal to be silent about systemic harassment, abuse, and inequity that people of marginalized backgrounds experience online. In a way, Dr. Kay’s theorization of clappin’ back reminds me of the origins of the long-standing Burmese satire, which has always intended to make the powerful and the elite uncomfortable, not be used as a tool to further oppress the marginalized.

In the following days after I found out about John’s comment, I reached out to several feminist colleagues. What could there be done? Is there something I could or should do? To whom can I report this? How should I deal with the trolls? All of them told me to ignore John and his comment, and advised me that the best way to deal with the trolls is not to engage with them. My colleagues are partially right in that ignoring, blocking, reporting,[5] limited engagement, and even leaving social media have been established as strategies for reducing harm when it comes to online harassment (Kulkarni et al 2024). Still, I felt disappointed, and amazed, by the lack of options available to a victim of online harassment.

To define who is a troll is incredibly slippery, just as the art of trolling itself. Cheng and co-authors (2017) argue that under the right circumstances, anyone can become a troll, especially based on the mood and the exposure to trolls (emphasis added). A way to deal with incessant trolls like John, as a woman of color and most importantly as a Burmese, is to refuse to stay silent, to document them, and to reclaim my ancestors’ practice of satire, which has always been a tool of talking back at the oppressor. Perhaps, instead of relying on rules, legal guidelines, and corporate moderation when trolling itself thrives on the pleasure of breaking those very rules and finding gaps in them, we should sharpen our skills in trolling back. Trolling back is a game of playing with words better than the trolls themselves.[6] Trolling back is not to take the trolls seriously, but to instead poke holes at their attack. In the game of trolling back, one jeers back at the trolls—more cleverly and ingeniously than they did. Whoever fails to poke back with more sass, pazazz, and wit than the other would be a loser.

At first, John’s trolling could come off as irritating, but it ultimately ended up being silly because it only exposes his lack of ability to comprehend our discussion unfolding only in Burmese. John was “not reading all of that” perhaps because he cannot be a master of all of those linguistic nuances in my mother(’s) language of Burmese. Perhaps he could never grasp, let alone reproduce, the richness of Burmese, just as I do. Or, John felt a need to troll me because he perceived me as someone more powerful than him.

And just like that, I might have just won this round!

Acknowledgement

I am grateful to Eddie for their digital labor in bringing John’s comment to my attention. Also, thanks to Edna Ei Htet for lending her voice, and Beyond Moon for reviewing my Burmese translation of the essay. Trolling back is more powerful in community!

Notes

[1] For example, John once spread a public rumor on social media that Dr. Maung Zarni, a scholar and an activist who founded multiple activist organizations such as the Free Burma Coalition, Free Rohingya Coalition, and Forces of Renewal Southeast Asia, did not actually complete his PhD from University of Wisconsin Madison.

[2] The post by “John” reads: “I’m not reading all of that, but fuck Chu May Paing. What a fraud.”

[3] The public comment by user “rogerrogerdc” reads: “Racism given an ‘intellectual’ veneer. Unfortunately academia has allowed the term ‘whiteness’, which intentionally targets a broad group of people based on a census designation, for ‘colonial’, which refers instead to a bundle of economic and social processes. The ‘scholars’ responsible for this drivel should be expelled from the academic programs that are hosting them.”

[4] A recording of the teach-in can be watched on Dr. KáLyn Coghill’s blog “hoodratscholarship.”

[5] I also decided to report John’s comment to his department. The chair, a woman-of-color anthropologist, responded quickly to me. While she sympathized with what I experienced, she also let me know that there were no legal guidelines to regulate social media and all she could do was to inform John’s advisor. I have yet to hear any updates.

[6] There is also a Burmese expression for this: “Attacking pleasantly” (သာသာလေးနဲ့နှက်). This means agitating your opponent/target only using nice and beautiful words instead of easily resorting to curse words, which may openly insult the other person, but shows one’s lack of linguistic wit.

This post was curated by Contributing Editor Paige Edmiston.

References

Bailey, M. (2021). Misogynoir Transformed: Black Women’s Digital Resistance. New York University Press.

Buckels, E. E., Trapnell, P. D., & Paulhus, D. L. (2014). Trolls just Want to Have Fun. Personality and Individual Differences, 67, 97–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.016

Cheng, J., Bernstein, M., Danescu-Niculescu-Mizil, C., & Leskovec, J. (2017). Anyone Can Become a Troll: Causes of Trolling Behavior in Online Discussions. Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, 1217–1230. https://doi.org/10.1145/2998181.2998213

Chu May Paing. (2020). Viral Satire as Public Feeling in Myanmar. In “Pandemic Diaries: Affect and Crisis,” Carla Jones, ed., American Ethnologist website. https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/collections/affect-and-crisis/viral-satire-as-public-feeling-in-myanmar/

Chu May Paing, & Than Toe Aung. (2021a). Talking Back to white “Burma Experts.” Agitate Now. https://agitatejournal.org/talking-back-to-white-burma-experts-by-chu-may-paing-and-than-toe-aung/

Chu May Paing, & Than Toe Aung. (2021b, April 23). Talking Back to white* Researchers in Burma Studies (Conference Presentation). Aruna Global South. https://www.arunaglobalsouth.org/post/talking-back-to-white-researchers-in-burma-studies-conference-presentation

Coghill, K. (2024, February 2). Playback: Clappin’ Back: A Look into Digital Misogynoir and Online Harm Reduction Practices [Medium]. Hoodrat Scholarship. https://medium.com/@hoodratscholarship/playback-clappin-back-a-look-into-digital-misogynoir-and-online-harm-reduction-practices-c256234eb5e1

Ferber, A. L. (2018). “Are You Willing to Die for This Work?” Public Targeted Online Harassment in Higher Education: SWS Presidential Address. Gender & Society, 32(3), 301–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243218766831

Golf-Papez, M., & Veer, E. (2017). Don’t Feed the Trolling: Rethinking how Online Trolling is Being Defined and Combated. Journal of Marketing Management, 33(15–16), 1336–1354. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2017.1383298

Herring, S., Job-Sluder, K., Scheckler, R., & Barab, S. (2002). Searching for Safety Online: Managing “Trolling” in a Feminist Forum. The Information Society, 18(5), 371–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972240290108186

Kulkarni, M., Durve, S., & Jia, B. (2024). Cyberbully and Online Harassment: Issues Associated with Digital Wellbeing. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.18989

Ortiz, S. M. (2020). Trolling as a Collective Form of Harassment: An Inductive Study of How Online Users Understand Trolling. Social Media + Society, 6(2), 205630512092851. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120928512

Owen, T., Noble, W., & Christabel Speed, F. (2017). Trolling, the Ugly Face of the Social Network. In New Perspectives on Cybercrime (pp. 113–139). Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Pfattheicher, S., Lazarević, L. B., Westgate, E. C., & Schindler, S. (2021). On the Relation of Boredom and Sadistic Aggression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 121(3), 573–600. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000335