In 2012, the first PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) drugs came onto the market, poised to revolutionize the field of HIV prevention. ‘The Pill’ promised to usher in a kind of sexual revolution, particularly for gay men and trans women. Sexual rights activists and health workers around the world analogized PrEP to birth control, suggesting that PrEP would allow particular sexual minority populations to secure bodily autonomy and serve as a tool for the self-management and mitigation of risk.

Anthropologists and other scholars have highlighted the logics of neoliberal sexual subjectivity upon which rational user models for PrEP are based (Thomann 2018; Dean 2015; Auerbach & Hoppe 2015). They have also pointed to issues around access and the ways in which PrEP maps on to dynamics of race and class, noting how PrEP has brought with it grand “End of AIDS” narratives that erase the ongoing struggles of People Living with HIV (PLHIV) (and particularly the experiences of queer people of color) (Thomann 2017; Benton et al. 2017; Moyer 2015). Medical anthropologists and STS scholars more broadly have long critiqued the techno-optimism of “magic bullets,” observing how fetishism around these objects and an emphasis on precision can lead to a distortion of situatedness, scale, or context (Redfield 2017; Biehl 2007).

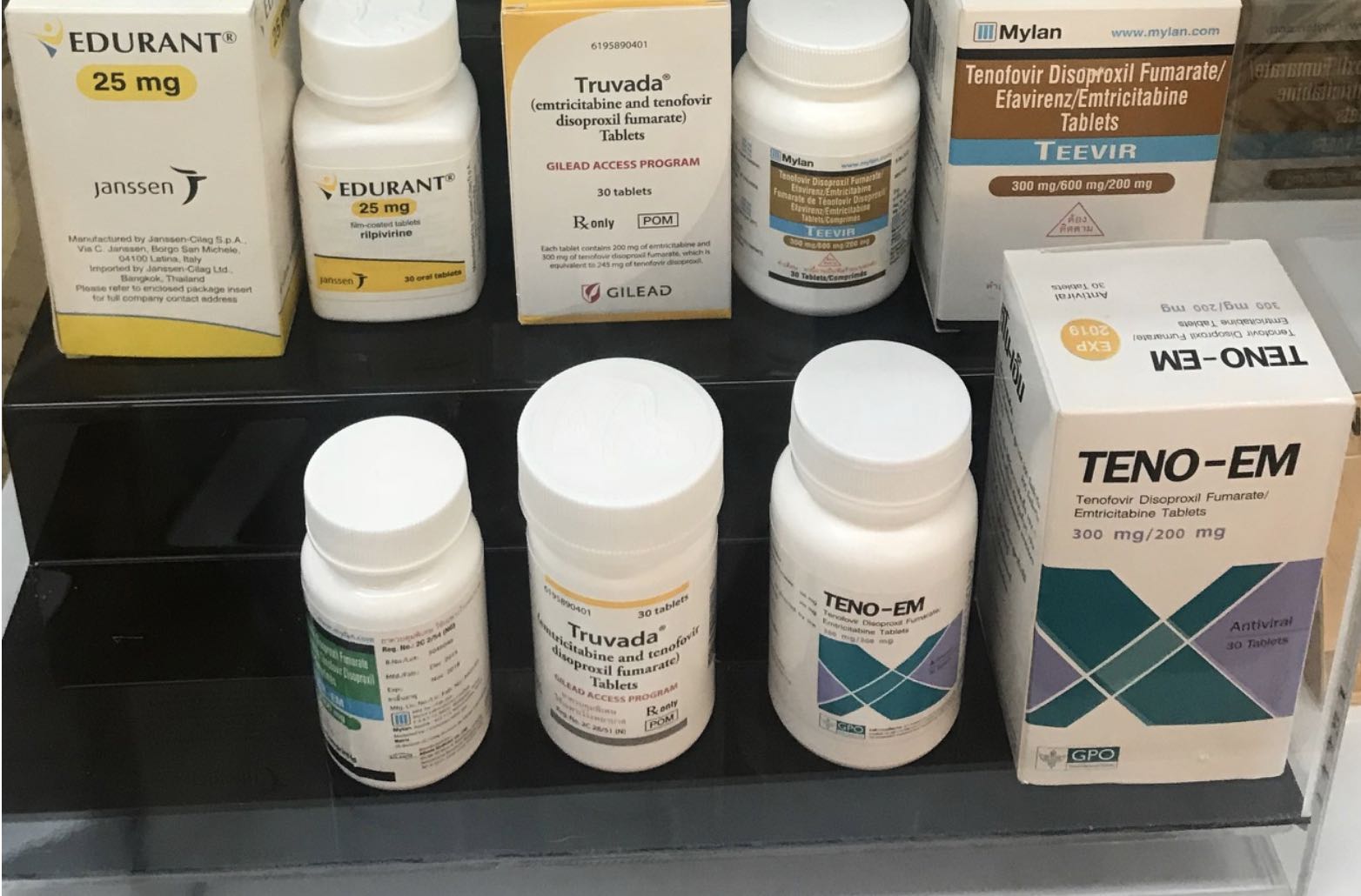

While pricing and access barriers make Gilead Science’s brand name Truvada unavailable in many parts of Asia, the Thai Government Pharmaceutical Organization has been manufacturing Teno-Em, a combination pill composed of the two same active ingredients as Truvada, since 2015. These state funded projects have made PrEP available to Thai citizens, non-Thai residents, and tourists in Bangkok for a price of less than a dollar a day.

A shelf containing different brands of HIV prophylactic treatments in a Bangkok clinic. Thai GPO Teno-Em is featured in the lower right-hand corner. Photo credit: author.

PrEP in Bangkok is much more than a therapeutic tool and thus is not solely embedded in an economy of therapy. While state health and NGO programs target domestic populations of men-who-have-sex-with-men (MSM) and transgender sex workers (TSWs) for PrEP services, regional PrEP promotion is also part of a strategic repositioning for the state – part of an attempt to secure a position within an emergent Asian biotechnical economy, while also capitalizing upon a growing regional LGBTQ+ market. Nonetheless, local sex workers (a population intensely targeted for therapeutic intervention) and queer/LGBT medical tourists (a consumer market heavily targeted through advertising for this ‘lifestyle drug’) demonstrate significant discrepancies in uptake.

A picture of a cartoonish PrEP mascot, with text reading “PrEP a day keeps HIV away. The photo is from a conference titled “PrEParing Asia: A new direction for HIV prevention among MSM in Asia. Photo credit: APCOM Foundation – Asia-Pacific Coalition on Male Sexual Health.

In Thailand, both ‘health’ and ‘happiness’ (which bear an etymological connection – kwaam suk ‘happiness’ literally quality or state of suk and sukhapaap ‘health’ literally image of suk) are particularly morally charged within contexts of health governance — and governance more broadly — taking on distinctive ethical and moral tones (for further elaboration on the role of moral authority in health governance in Thailand, see Funahashi 2016). The management of disease has likewise been central to state building and national economic development strategies. Much of Thailand’s modern health infrastructure was built by the monarchy and U.S. investment, fueled by what Alan Klima has referred to as a “military-gift” economy generated by overlapping strategic interests between U.S. empire in the region and the monarchy/state’s desire to keep its national geopolitical body free of infection from an epidemic of communism in Southeast Asia (Klima 2002). Indeed, Thailand’s positioning as the primary site for R&R for American GI’s during the Vietnam War is a significant historical reason for the emergence of a nexus of medicine, hospitality, tourism, and sex work. The first national programs to address venereal disease also emerged in that era, while contemporary cosmetic surgery clinics, as well as gender confirmation clinics (for which there is also a global tourism market: see Aizura 2018), draw their historical roots from infrastructures and expertise linked to American military surgery and prosthetics. These infrastructures were designed for American occupying forces. When the Americans left, the infrastructures remained with no substantial domestic consumer markets to take their place, hence consistent efforts to continue to bring outsiders in.

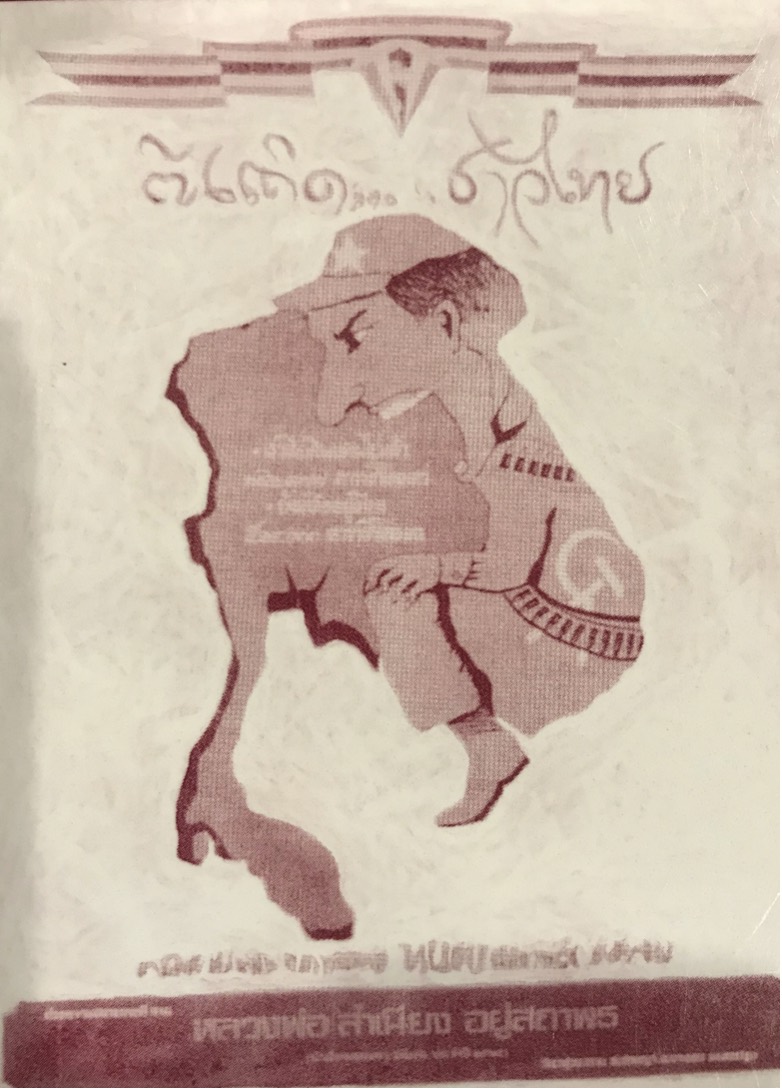

Cover art from Thongchai Winichakul’s germinal Siam Mapped: A History of the Geo-Body of a Nation, showing anti-communist propaganda, depicting Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos as a communist soldier about to eat the national body of Thailand.

In the early years of Thailand’s HIV epidemic, infection rates were concealed or downplayed to abate perceptions of risk as the nation sought to transition away from a military-gift economy and towards securing foreign direct investment. When the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis challenged foreign direct investment-based strategies, pharmaceutical sovereignty and health-centered approaches to development became a central aspect of a pivot away from manufacturing and towards service industry work, tourism, and a growing health and wellness sector. After the 2014 military coup, the military staged “return of happiness” street parties, replete with things like free medicines, and a song (“Returning Happiness to the People”) penned by General Prayuth Chanocha himself. PrEP was likewise made free in 2017 to celebrate the birthday of Princess Soamsawali, who is the royal patron and public face of much of Thailand’s HIV prevention work. She is largely lauded for her role in helping Thailand become the first nation in the region to eliminate the transmission of HIV through breast milk. The Princess PrEP Program, also named after her, was a pilot project that paid and trained members of key populations to promote PrEP to their peers and link them to community health centers, laying a blueprint for the expansion of domestic PrEP services. Today, “The Land of Smiles” – which simultaneously functions as a nationalist slogan, a statement on happiness and health, and a tourism brand/catchphrase – continues to be emblematic of this assemblage of benevolent health-led tourism focused development.

Free immunizations and wellness screenings at the “Return of happiness” street festivities after the military coup in 2014. The picture shows a person receiving a shot from a nurse. Photo credit: The Guardian.

In 2019, The Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT), a government entity charged with overseeing what some accounts estimate as nearly 20% of national GDP, established a division and campaign focusing exclusively on LGBT+ tourism. The irony of their slogan, “Go Thai, Be Free,” is not lost on some of my interlocutors who recall the military government arresting people for the public consumption of sandwiches not so long ago. Nonetheless, the availability of Thai PrEP builds upon preexisting patterns of queer migration and tourism in the region, capitalizing upon Bangkok’s already eminent and carefully curated image as a modern gay paradise (Jackson 2011, Kang 2011). PrEP, in this context, is not only a tool within a public health project, it is also part of a particular national imaginary bound up with a tourist industry, that relocates both medical and queer sexuality modernity away from ‘the West,’ and constructs it in Bangkok. That modernity, however, is distinctively cosmopolitan and regional, and is not for everyone.

Posters from a TestBKK PrEP campaign. On the left, two men showering together, with text that reads: “Have fun without fear.” In the center, two men are on a couch together, making a heart sign by putting their hands together. It reads: “Get close together, without fear anymore.” On the right, a shirtless man on the couch with an tablet device, with text that reads: “Offering professional services, don’t need to fear anymore.” Photo Credit: TestBKK APCOM Foundation.

The emergence of a new virus, for which there is neither a therapeutic nor a prophylactic treatment, has further revealed the fault lines upon which the political economy of PrEP in Thailand was constructed. With fewer than 4,000 infections and fewer than 100 deaths, the Thai state’s biosurveillance and national health apparatus has been largely successful in containing the novel coronavirus. Sexual economies and economies of tourism, on the other hand, have been decimated. I, like many other graduate students, have been struggling with how to do fieldwork during a pandemic. With a methodology previously organized around a logic of “following the object” (Marcus 1995), what to do when the “object” has all but receded from view? Tourists stay at home, PrEP users hold on to their pills saving them for an imagined future return to “normalcy”, while nightlife venues and Bangkok’s queer and intimate economies are all closed. Yet what can PrEP’s retreat during this time tell us? With the magic bullet’s magic temporarily suspended, what might we learn about the kinds of relations and inequalities that held together the infrastructures of PrEP’s circulations to begin with?

One of the most brutal revelations is the seeming expendability of sex worker lives, particularly trans/kathoey[1] and (rural-urban) migrant sex workers, the moment they stop generating lucrative profit within the sex-tourism industry. Precisely those who are supposed to benefit “the most” from state-subsidized PrEP provision, many sex workers now find themselves homeless or living in go-go bars and clubs that have been shut down since March. It is clear that the “care” that they receive from the state was never imparted as a relational obligation of rights or citizenship, nor did it ever extend beyond the provisional procurement of ‘a pill.’ With sex work still technically illegal and criminalized in Thailand, despite its ubiquity and a widespread awareness of the revenue that it generates, sex workers are considered self-employed and are ineligible for the unemployment benefits the state is offering to encourage people to stay home. During COVID, they can only rely on themselves, their communities, and their networks, with many workers returning to the countryside to move back in with families they left for the city.

A go-go bar on Walking Street in Pattaya with a sign reading “For Rent”. Many bars and nightlife venues have been transformed into makeshift housing. Photo Credit: Sky News.

Service Workers in Group (SWING) is a community organization previously at the fore of communicating knowledge about PrEP and promoting access for sex workers in Bangkok and Pattaya. Originally part of the vehicle for getting state manufactured chemical prophylaxis into “high-risk bodies,” SWING now finds its HIV efforts secondary, relying on private donations and their own fundraising to provide their community constituencies with basic metabolic sustenance. While there are public funds for HIV related programming, they’ve shifted towards volunteer labor and private funds in order to run a full time food bank operation. They are also distributing materials and protective equipment to workers who are still working, while creating a resource database through social media providing tips on how to have safe sex and do sex work during a pandemic.

Bags of rice sit upon a desk in a SWING office. Service Workers in Group, a community-based organization for sex workers formerly at the fore of PrEP promotion, now runs an extensive food bank and food distribution operation. Photo Credit: SWING Organization.

Boxes of Mama noodles sit upon chairs in a SWING community center office. Photo Credit: SWING Organization.

Meanwhile, the Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT) and national health authorities are closely collaborating in order to implement a grand reopening plan – one that capitalizes upon Thailand’s “successful” response to the coronavirus and posits Thailand as a COVID-free getaway for those who can demonstrate their negative status and who want to escape quarantine, stay at home orders, and botched public health responses in other countries. Many health, wellness, and luxury resorts are offering quarantine package deals at discounted rates, as an alternative to state-funded isolation and a way to keep those in the formal hospitality industry employed (and off of state unemployment insurance). While some sex workers advocacy groups have begun to ask for formal recognition of sex work’s relevance to the tourist economy, demanding that sex workers be formerly included in the tourism reopening plan, fear that results from the continued criminalization of sex work prevents broader political mobilizations. The state’s response to COVID resonates with earlier responses and tourism promotion in relation to HIV and venereal disease – a response geared at orienting domestic service, consumer, and medical infrastructures towards upper-class Bangkok consumers and a foreign consumer market.

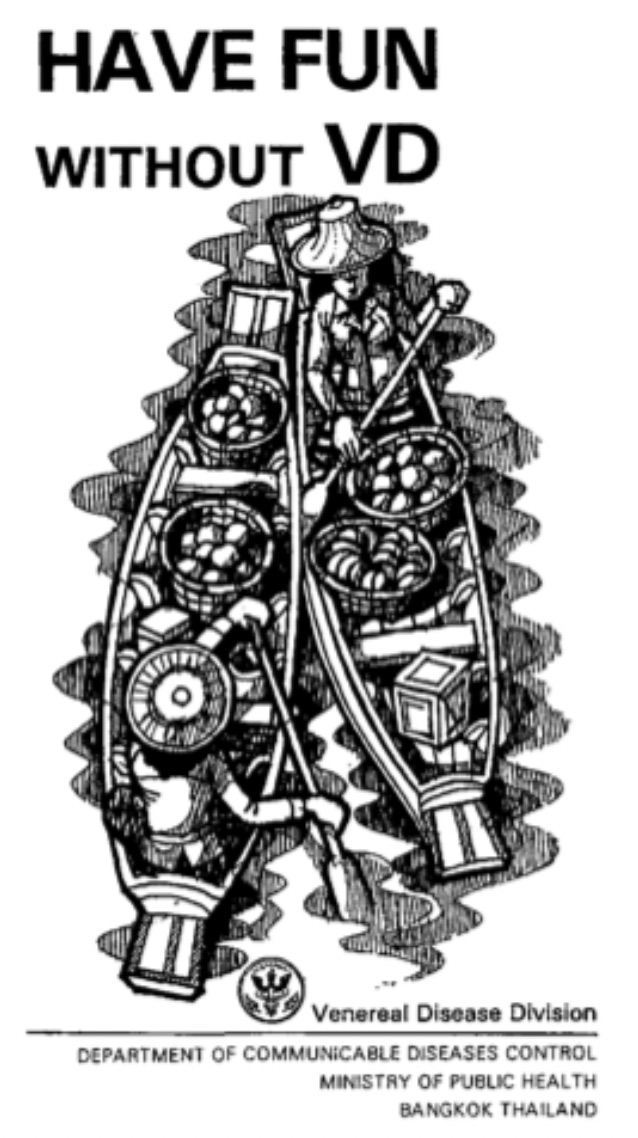

A Thai Ministry of Public Health Pamphlet circa 1988, borrowed from Ara Wilson’s The Intimate Economies of Bangkok: Tomboys, Tycoons, and Avon Ladies in the Global City. The image shows a floating market, one of the most iconic tourist attractions and the focus of intense tourism promotion at the time. On top, it reads “Have fun without VD.” Photo Credit: Ara Wilson, The Intimate Economies of Bangkok.

As the world’s economies begin to open back up and Thai Teno-Em PrEP resumes its regional and transnational circulations – let’s not forget this juncture where “things” came undone, and the economies that produced them came to a halt. In this moment, the very same bodies targeted for chemical prophylactic intervention in the context of a robust tourist economy are being denied basic chemical nutrients (food) for the sustenance of life, falling out of formal infrastructures of care, and instead landing in the care of their own community, kin, and local networks. As (and if) things return to “normal” and the Thai state picks up the mantle of sexual health again, let’s remember the limits of care that were exposed in this moment, noting how care was practiced beyond the limits of the state.

[1] Kathoey refers to a Thai denotation that overlaps with but is distinct from Euro-American ideas of trans-ness. It has been claimed by or used to refer to what English language speakers might think of as a male-to-female transgender persons, people who embody effeminate forms of homosexuality, a third gender, or a second category of womanhood (phuying praphet song).

References

Aizura, Aren Z. 2018. Mobile Subjects: Transnational Imaginaries of Gender Reassignment. Duke University Press.

Auerbach, Judith D, and Trevor A Hoppe. 2015. “Beyond “getting drugs into bodies”: social science perspectives on pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV.” Journal of the International AIDS Society. vol. 18:4.

Benton A, Sangaramoorthy T, Kalofonos I. 2017. Temporality and Positive Living in the Age of HIV/AIDS–A Multi-Sited Ethnography. Current Anthropology. vol. 58:4.

Biehl, João Guilherme., and Torben Eskerod. 2007. Will to Live: AIDS Therapies and the Politics of Survival. Princeton University Press.

Dean, Tim. 2015. “Mediated Intimacies: Raw Sex, Truvada, and the Biopolitics of Chemoprophylaxis.” Sexualities. vol. 18:1–2

Funahashi, Daena. 2016. “Rule by Good People: Health Governance and the Violence of Moral Authority in Thailand.” Cultural Anthropology, vol. 31:1.

Jackson, Peter A. 2011. Queer Bangkok: 21st Century Markets, Media, and Rights. Hong Kong University Press.

Kang, Dredge. 2011. “Queer Media Loci in Bangkok: Paradise Lost and Found in Translation.” Glq-a Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies.

Klima, Alan. 2002. The Funeral Casino: Meditation, Massacre, and Exchange with the Dead in Thailand. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Marcus, George E. 1995. “Ethnography in/of the World System: The Emergence of Multi-Sited Ethnography.” Annual Review of Anthropology. vol. 24.

Redfield, Peter. 2018. “On Band-Aids and Magic Bullets.” Limn. limn.it/articles/on band-aids-and-magic-bullets/.

Thomann, Matthew . 2018. ” ‘On December 1, 2015, Sex Changes. Forever’: Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis and the Pharmaceuticalisation of the Neoliberal Sexual Subject”. Global Public Health vol.13:8.

Thomann, Matthew et al. 2018. “’WTF is PrEP?’: attitudes towards pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men and transgender women in New York City.” Culture, Health & Sexuality vol. 20:7.