Each year, Platypus invites the recipients of the annual Forsythe Prize to reflect on their award-winning work. This week’s post is from 2016 winner Eben Kirksey, for his book Emergent Ecologies (Duke, 2016).

Surprising hopes can proliferate against the backdrop of seemingly impossible odds, dashed dreams, and disappointing circumstances.[1] Looking to possible futures, rather than to absolute endings, Jacques Derrida celebrated forms of hope that contain “the attraction, invincible élan or affirmation of an unpredictable future-to-come.”[2] “Not only must one not renounce the emancipatory desire,” wrote Derrida, “it is necessary to insist on it more than ever.”[3]

In the days after Donald Trump was elected President, as Republicans begin to lock in control of the legislative and judicial branches of the US government, it would be easy for people committed to social and ecological justice to resign the future to fate. Converting despair to hope involves playing with the uneasy alchemy of the pharmakon, that is, turning obstacles into opportunities, transforming poison into a cure.

As an emergent social movement in the United States works to trump hate with love, strategies and tactics might be borrowed from Latin American intellectuals who have turned blasted landscapes into flourishing ecosystems, who have worked to ground hopes in shared futures with endangered species. The long legacy of US hegemony in the Americas left countries like Panama riddled with unexploded bombs and divided by systems of apartheid. Cattle and capitalism destroyed the forests of Costa Rica. Yet legions of organic intellectuals have responded by gardening in the ruins, by caring for diverse kinds of life amidst ongoing disasters.

Milton Brenes, the coordinator of a reforestation program at the bi-lingual Monteverde Cloud Forest School in Costa Rica, is working to create a shared future with a multispecies community he loves. Photograph by author.

Milton Brenes, the coordinator of a reforestation program at the bi-lingual Monteverde Cloud Forest School, for example, is working against general feelings of anxiety about the environment to create a shared future with a multispecies community he loves. On eleven hectares of derelict pasture in the highlands of Costa Rica, Milton is recreating a forest in collaboration with plants, animals, and students. Amidst major ecological and economic transformations, Milton has aligned the interests of heterogeneous life forms, creating an assemblage of multiplicities. An ecosystem has emerged in this derelict pasture, a riotous collection of strangers. Rather than try to hive off “nature” from “culture,” Milton has cultivated diversity. For him, diversity is a hybrid product of mestizaje, where a diversity of taxonomic forms, a diversity of uses in indigenous traditions, and a diversity of articulations with market economies all matter.

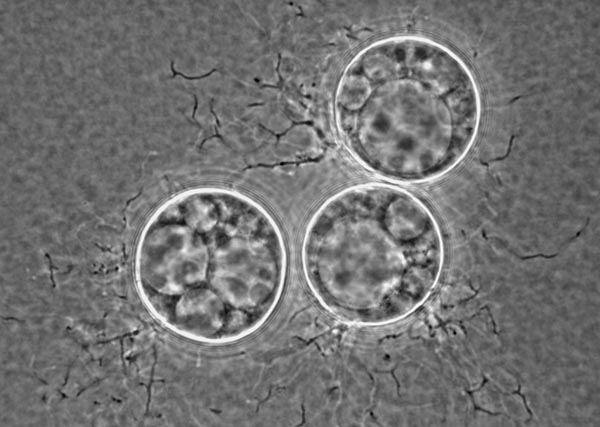

Microscopic chytrid fungi, which are killing frogs en masse, appear to be dark bubbles within bubbles. Photograph and microscopy by Joyce Longcore.

Emergent diseases, unwittingly spread by people, also figure into the book. A microscopic fungus, a kind of chytrid, has spread through the Americas—on the boots of hikers, on the backs of laboratory animals, and on the toes of migratory waterfowl. This chytrid is killing frogs en masse, and a handful of conservation biologists have responded, trying to focus their hopes on the living figures of these animals, caring for frogs alive amidst hostile forces and prevailing sentiments of indifference.

As Trump assumes office it will be increasingly difficult to disavow feelings of indifference—e.g., “it is too late, the world is shit.” “Having someone to care for, and thus caring for what happens, caring about whether there is a future or not,” is critical, writes Sara Ahmed. Hope involves vulnerability when you “care for that which is beyond or outside your control.” Hope, in other words, means caring about “the hap of what happens.” Emergent Ecologies adopts these insights from Ahmed to consider the practical and imaginative labor that is becoming increasingly urgent amidst radical political shifts in the United States and Europe.

A multitude of tinkerers and thinkers are transforming feelings of futility into concrete action, cynicism into happiness and hope.[4] Sustaining multispecies families, tending compost bins, and sorting through the detritus of capitalism, these creative agents are caring for things and beings that are ready at hand.

Past winners of the Forsythe Prize—especially Heather Paxson, João Biehl, Rayna Rapp, Emily Martin, S. Lochlann Jain, Joe Dumit, Cori Hayden, and Stefan Helmreich—have long inspired my own thinking and research. It is an honor to join this distinguished company with Emergent Ecologies. I will count the book successful if it helps catalyze some uneasy alchemy—affirming the necessity of hope and care in an era of radical right-wing political change.

Endnotes

[1] “The very idea of the messianic brings the whole feeling of dashed hopes and impossibility along with it,” according to literary critic Frederic Jameson. “You would not evoke the messianic in a genuinely revolutionary period, a period in which changes can be sensed at work all around you.” Jameson, “Marx’s Purloined Letter,” 62.

[2] Derrida, Marx & Sons, 253.

[3] Derrida, Specters of Marx, 74.

[4] This paragraph is in close dialogue with an anonymous pamphlet called Desert, written by “a nature loving anarchist,” which suggests that many activists, anarchists, and environmentalists are haunted by a realization: “the world will not be ‘saved.’ Global anarchist revolution is not going to happen. Global climate change is now unstoppable. We are not going to see the worldwide end to civilization/capitalism/patriarchy/authority… This realisation hurts people.” Thanks are due to Anna Tsing for pointing me towards this pamphlet and for also showing me how to garden in ruins. See Anonymous, Desert, 7-8, accessed September 19th, 2014, Anonymous, Desert, http://theanarchistlibrary.org.

1 Trackback