Editor’s Note: This is the third post in our Law in Computation series.

When we play an online game like World of Warcraft, where are we? This is not just a metaphysical question—are we in the fantasy world of Azeroth or in front of our computers—but a legal one as well. And there are multiple answers to that legal question. We might take a look at the space of intellectual property at the level of code and creation, whether corporate or by the players. There is also the space of law within the game, of the rules and norms guiding play (De Zwart and Humphreys 2014). What I’m concerned with here, though, are the servers, located in physical places, that connect players through infrastructures of connection whose worlds are sometimes disconnected by proprietary and computational decisions of game world owners.

Servers keep online games alive. When online gamers talk about a game world being disconnected, they often point to the server as being “unplugged” or “turned off.” While official game servers are typically owned by game developers and corporations, players are now harnessing this power themselves, using privately-owned servers (“private servers”) as a viable solution for restoring and sustaining older versions of online games previously consigned to oblivion. But why?

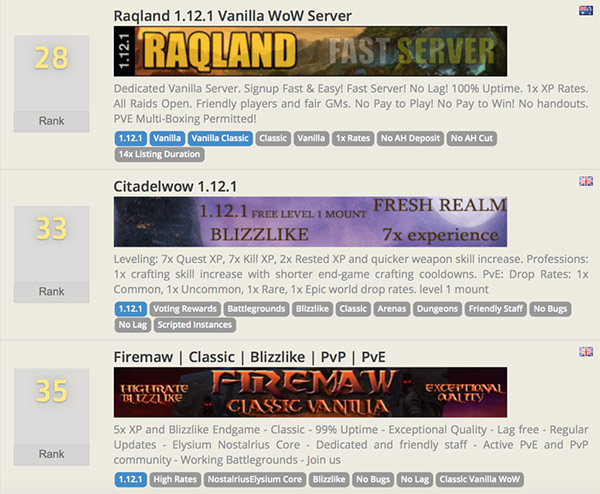

Ranking and advertising private World of Warcraft servers located in different regions. Source: https://topg.org/wow-private-servers/version/Vanilla-Classic/

Game developers encourage players to continue occupying these corporate-owned online gaming spaces—and paying monthly fees depending on the game—by issuing modifications to the game world via smaller tweaks (i.e., patches) and larger transformative content additions (i.e., expansions). These changes are often permanent, reshaping landscapes, user interfaces, and social norms. As a result, previous editions of the virtual world cannot be revisited. Over time, online game worlds might change so much that players feel that something has been taken away from them, that they have lost control over a space and a community (Crenshaw and Nardi 2016). This loss fuels a nostalgic longing for what has been rendered obsolete. And right at this very moment, thousands of people still come together on private servers to play out-of-date versions of World of Warcraft that are no longer commercially available, like the original (or “vanilla”) version from the mid-2000s.

My research is broadly concerned with game servers—those usually distant and backgrounded digital technologies that make online gaming possible. Ethnographically I focus on these servers’ technical and spatial features, as well as players’ memorial and affective practices, like collecting pieces of commemorative server hardware. And as more and more players move to private servers to game nostalgically, I find myself taking a closer look at the expanding world of private server gaming, especially when it is unauthorized and criminalized.

This means I have stepped, rather reluctantly, into the world of law.

In recent years, private servers running older World of Warcraft software have become especially numerous, and increasingly they are being forced to shut down. Yet the question here is not whether private servers are legal—because, typically, they aren’t—but how private server gamers and the class of server maintainers create new forms of legal engagement online, changing the social realities of online gaming. I examine how these groups strategize avoidance of intellectual property laws and justify breaking laws; and how they make sense and make use of sociolegal objects, like Terms of Service and cease and desist letters, as well as their own positioning within legal frameworks (i.e., what some legal scholars call their “legal consciousness” [Silbey 2005]).

World of Warcraft Classic logo. Source: Blizzard Entertainment.

In addition to exploring the personal experiences of players, I study dynamics of authorization in the context of private server gaming (Dent 2016), asking how and to what degree private servers are considered to be legally permissible or socially acceptable. This means examining how game companies, media sources, and other gamers criminalize or sanctify these practices and question the very existence of private servers. When players are calling them private servers, but game companies call them “pirate servers,” the difference in rhetoric is difficult to ignore. This is further complicated by the announcement that, very soon, there will be official, authorized, subscription-based servers running “World of Warcraft Classic.”

What began as an admittedly reluctant foray into questions around legality and intellectual property has become a fascinating part of my overall dissertation research project that makes this work even more critical and legible beyond online gaming. For instance: many of these servers’ development teams, cognizant of corporate legal power, operate outside the United States as a strategy to avoid US-based companies and intellectual property claims. How might such tactics relate to contemporary issues surrounding data geolocation in cloud computing, like data localization laws? How does unauthorized gaming practice reflect broader concerns around the materiality of data, the residence of data, and the regulation of information? Through energizing collaborations among graduate student fellows in the Technology, Law, and Society program and in planning the upcoming Summer Institute, I’m applying concepts and methodologies from legal anthropology and law & society literature to enhance my own project and meaningfully connect it to other socio-technical-legal issues facing us in our current moment.

References

Crenshaw, Nicole, and Bonnie Nardi. 2016. “It Was More than Just the Game, It Was the Community”: Affordances in Social Games.” Proc. of HICSS.

De Zwart, Melissa, and Sal Humphreys. 2014. “The lawless frontier of deep space: Code as law in EVE online.” Cultural Studies Review 20 (1):77.

Dent, Alexander S. 2016. “Intellectual Property, Piracy, and Counterfeiting.” Annual Review of Anthropology 45:17-31.

Silbey, Susan S. 2005. “After legal consciousness.” Annu. Rev. Law Soc. Sci. 1:323-368.

1 Trackback