*Many of the names and places mentioned below have been changed.*

While the FARC (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia or Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) have sometimes been categorized as a ‘peasantist’ (campesinista) guerrilla group (Pécaut 2013), in seeking to capture the attention and support of urban and border zones, this group—first as a guerrilla organization and currently as a political party—has employed a variety of mechanisms and media platforms, among which the appropriation of online spaces is especially noteworthy.

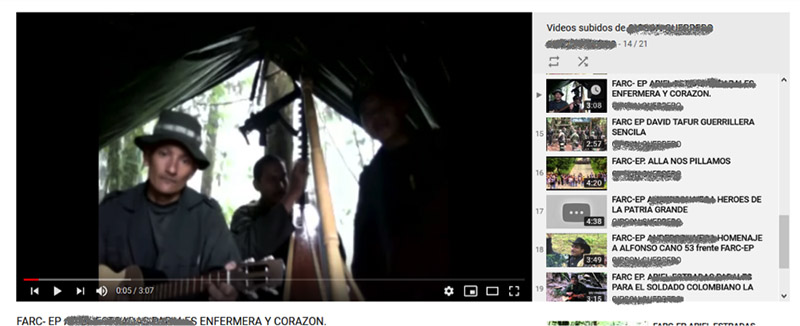

Among the digital artifacts the FARC have produced online, YouTube music videos are of particular interest. By studying these videos, and how they circulate, we can not only gain a better understanding of the currently understudied representational tactics of the FARC, but also problematize how we understand the ‘presence’ of this armed group in times and spaces of war. It can be argued that these online spaces—combining digital audiovisual content with representational discourses that contradict the predominantly negative and dehumanized image of the FARC—have allowed this insurgent group to establish an alternative presence in the public sphere, and engage with a broad variety of audiences. In this post, through the particular experiences of a former member of the FARC who has uploaded music videos to YouTube, I will explore how the presence of the FARC is materialized in different spaces.

Cultural Production in Wartime

Musical practices within the FARC have long contributed to the interconnectedness of this guerrilla group at both regional and national levels, as well as its consolidation as a cohesive collective (Bolívar 2010). Although vallenato is the most prominent and popular style of FARC music, there have also been a number of well-known joropo songs, a music style from el llano—the eastern plains of Colombia. Andrés Espinosa, an ex-FARC combatant, is known for his joropo-style compositions. He worked as both a joropo composer, as well as part of the team that run the FARC’s clandestine radio station. While I initially talked to Andrés because of my interest in his music career, his story drove home the interrelatedness of musical and communicational practices, clearly seen in both his work on the radio and in the creation and publication of YouTube videos.

Andrés had been interested in the music of his region—llanera or joropo—since he was a child. At age 14, he joined the FARC, and continued to dedicate much of his time to music. For him, one of the main roles music has played within the FARC has been “letting people know who they are” (dar a conocer las FARC) so that they “realize that we’re not like those people who are being smeared every day in the bourgeois media.” (Espinosa 2017). The songs he wrote in times of conflict described his everyday experiences in the middle of a war, his admiration for his leaders, and his reasons for having joined the armed confrontation. Andrés’s compositions are similar to others who were active in the cultural production of the FARC. FARC artists sing about love stories, wartime experiences, comrades lost on the battlefield, and about their everyday lives (Bolívar 2010). It should be noted, however, that for Andrés, musical production was accompanied by audiovisual production, and in general by the communicative tasks he was given. As such, he and other guerrilla members with similar responsibilities often had to learn new technical skills by trial-and-error.

The Circulation of Music Videos

The use of video cameras and audiovisual software was restricted to members of the militia who worked in communications. Andrés, who worked in this field, took photos and made videos with which to complement his musical compositions, as well as those composed by other militia-members interested in music. At the outset, these videos were circulated on flash drives, and were limited to guerrilla members and the peasants who lived within their circle of influence (Espinosa 2017).

Although during wartime he composed several songs with which he paired audiovisual content, it wasn’t until 2013, as the peace negotiations with the state were underway, that Andrés decided to upload his audiovisual content to YouTube.

Andrés describes both the act of composition and that of putting his videos online as difficult in wartime. Not only does he emphasize the loss of musical instruments and equipment in bombings, but also the risk of being “burned” (quemado)—discovered—for publishing FARC videos on the Internet (Espinosa 2017). In 2013, while peace talks were ongoing, no treaty had yet been signed. In that period of uncertainty about the success of peace talks, Andrés’ music video posts constituted a risky and defiant act, starting with the fact that most of his songs defended the FARC’s decision to take up arms and spoke positively about the combative role of its members.

Inhabiting and “Being There” in Public Space

Since digital practices are linked to individuals’ everyday offline practices, online spaces become an extension of public space which is possible to “inhabit” (habitar) (López 2016). Cybernauts come into contact with an enormous number of digital artifacts that hold the potential to spark dialogue or reflection about social problems (Trejo 2002). In this way, interaction and exchange are central points of inquiry for understanding the ways we inhabit public space. Andrés’ YouTube posts promote practices such as watching and commenting on the content of the videos, and as such make interaction between individuals possible. People participating in these digital exchanges gradually begin to “be present”” (estar presentes) in and inhabit this public sphere, made wider by online spaces.

The concept of “being there” when social practices are imbricated in both on- and offline spaces has been widely debated in ethnographic circles. These discussions have permeated the principles of digital ethnography and taken up the ideas of multi-sited ethnography, designed through overlapping networks and locations in which the ethnographer seeks to establish a kind of presence that connects the multiple spaces in question (Marcus 1995). The idea that ‘“being there’” is fundamental to anthropological fieldwork has inspired the concept of “thick presence” (Mollerup 2016), highlighting forms of presence that are meaningful for the generation of ethnographic knowledge. The triad Mollerup proposes consists of 1) co-location, 2) the presence of there here, and 3) our presence there. Mollerup proposes that the view counter on YouTube can also be considered a type of presence which, while different from the images and sounds that animate our computer screens and are in some way “there” with us, continue to constitute a meaningful presence.

Taking this problematization of the meaning of “presence” as a starting point, one could argue that individual digital practices are immersed in dynamics in which multiple temporalities and localities are juxtaposed to configure ‘“presence”’ online as an extension of public space. Andrés’ music video posts on YouTube constitute a practice that makes possible different forms of “being there,’ and allows interaction and dialogue between actors (through comments or the number of views) which could not be established in other spaces. In this way, FARC members and their discourses also begin to inhabit public space, through YouTube videos. Nonetheless it should not be taken for granted that these spaces are not free from power relations and hierarchies. Being present in these spaces does not necessarily guarantee them the possibility of engaging in equitable exchanges with their detractors.

Another of Andrés’s videos, called “The Warrior Girl.”

Material Conditions and Technical Know-How

Presence in these spaces is also contingent on the material conditions in which technology is used. The requirements for acquisition of Internet equipment or audiovisual editing software, and the technological know-how to use these tools, show the differences and limits in access to and the appropriation of these media. While these differences correspond to current predominant power relations, the advent of the Internet has nonetheless opened a space without which many digital artifacts would never have seen the light of day (Trejo 2009).

The particular uses the FARC has given to these media are directly related to the specific approach to technology of this guerrilla organization in wartime. Andrés, for example, gained familiarity with the Internet thanks to a mission he was sent on in an urban area. It was there that he uploaded the videos, despite the risk he was taking by being in a city, or as he called it, a hot spot (un sitio caliente). In the same way, in his work on the radio station, he learned how to use computers and transmission equipment. They were part of his everyday life “en la montaña” (in the mountains) (Espinosa 2018.)

The role of the Internet and other technologies in the processes of mediatization that configure the public sphere urge us to study forms of individual appropriation of these media (Bonilla 2012). Andrés told me that, in a very conscious way, his content was directed at an urban population. “The Internet has always been for city people,” where there are some who “don’t understand our reality,” he explained to me (Espinosa 2017). This statement lays bare a concern within the FARC about the imbalance of information available in urban vs. rural settings. The Internet has become a tool to contest the information circulating about the FARC in sectors that are difficult for them to reach, and in a space they can inhabit while staying out of reach of the state.

References

Bolívar, Ingrid. 2010. Unheard Claims, Well-Known Rhythms: The Musical Guerrilla FARC-EP (1988–2010) en Fanta, Andrea, Et. Al. 2010. Territories of Conflict. Traversing Colombia through cultural studies, University of Rochester Press, 209-220

Bonilla, Jorge. et. Al. 2012. De las audiencias contemplativas a los productores conectados. Mapa de los estudios y de las tendencias de ciudadanos mediáticos en Colombia, Sello Editorial Javeriano, Bogotá

López, Matías. 2016. Aproximación a la esfera pública contemporánea: habilitaciones desde la producción cultural. Revista Encuentros, Universidad Autónoma del Caribe. Vol. 14 -02, 141 – 157

Marcus, George. 1995. Ethnography in/of the World System. The emergence of multi-sited ethnography” (1995), en Annual Review of Anthropology, núm. 24, 95 – 117. ALTERIDADES, 2001 11 (22), 111-127

Mollerup, Nina G. 2016. ‘Being there’, phone in hand: Thick presence and ethnographic fieldwork with media Working Paper for The EASA Media Anthropology Network’s 58th e-Seminar

Pécaut, Daniel. 2013. La experiencia de la violencia: los desafíos del relato y la memoria, La Carreta Editores, Medellín

Trejo, Raúl. 2009. Internet como expresión y extensión del espacio público. Revista MATRIZes Vol 2, No 2. Perspectivas Autorais nos Estudos de Comunicacao IV, 1-16.

Interviews

Andrés Espinosa, August 17,2017 and March 23, 2018