There are collections of embarrassing childhood photos stashed in most parents’ homes. Everyone remembers an instance when those photos unexpectedly appeared in ways that were awkward or humiliating, such as in a graduation slideshow or the stereotyped first-date-meets-the-parents scenario. For previous generations, those images were hard-copy, faded, dog-eared, and easy to hide under your bed. They also came in limited supply, due to the costs of cameras, film, and film processing.

For today’s children (and parents), things are different. We create more images thanks to the cameras on mobile phones, share them more widely through the internet, and have no idea how to destroy them. In this evolving sociotechnical reality, what should parents do? Should we succumb to the social pressure to share online photos of our children’s most adorable and incriminating moments, thereby “sharenting”? (And even make money from it, as social media influencers?) Or should we respect our children’s right to privacy and control over images of themselves?

This question draws on the unknowability of the risks of using new technologies. One helpful way to think about this conundrum is the classic Collinridge dilemma, which explains that 1) the social implications of a new technology cannot be well understood until that technology has been widely adopted, and 2) if those implications are undesirable, they are very difficult to mediate after the technology is widely used. (Also see Kudina and Verbeek, 2018.) This paradox seems unsolvable. For example, how can we as a society reduce harm and increase benefit before we know what the impacts of widespread photo-sharing are? Once those impacts become clear, what can we do to mitigate any harms? And what does this mean for how parents should behave?

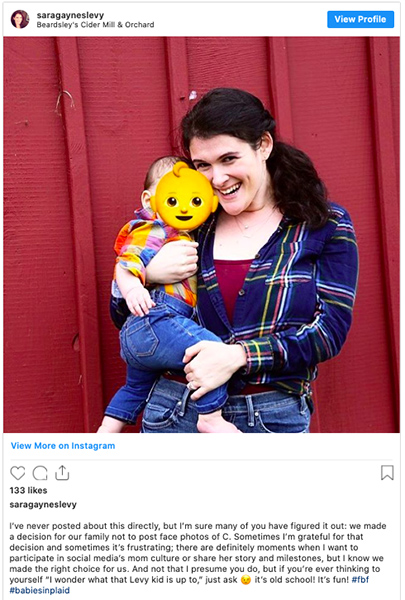

Some parents edit photos of their children to hide their identity on social media (image from Levy, 2019).

Sharing snapshots of cute babies on social media or blogs seems innocuous and produces very motivating rewards for the sharer in the form of “likes” and admiring comments. However, it is increasingly obvious that the internet enables data, including images, to circulate in ways that the makers of those data don’t expect or desire. (For one relevant example, consider the case of engineers co-opting kids’ pictures from Flickr to create datasets to develop surveillance systems through machine learning.) In the case of sharing photos of children, the people portrayed in those data are the ones who bear the potential long-term consequences, while the people who share those data (e.g., parents) enjoy the short-term rewards.

I faced this ethical quandary when I became a parent this year. I just assumed that I would post the typical double-portrait-in-hospital-bed to announce my child to my online communities. After all, I love admiring my friends’ children via online photos, and I felt some need to reciprocate. And, let’s be real, kind online comments feel rewarding, which was an especially powerful motivator for me as a sleep-deprived, hormone-flooded new parent. But within days of my child’s birth, my iPhone could identify the tiny, wrinkly infant face. It made me uncomfortable to see that brand-new face categorized and labeled, so I googled how to turn off that facial recognition feature. I was shocked to learn that you cannot opt out of it. My family didn’t even know my child yet, but Apple did.

Besides the deep discomfort I felt about facial recognition, what was the harm? I asked my parent-friends and searched for resources about this question, and learned that the primary concerns include:

- the child’s physical safety, e.g., that a photo shows what they look like and can reveal their current location, thus facilitating kidnapping,

- the child’s right to consent to how their image is used (which some children have asserted by actually suing their parents for image-sharing),

- dystopic uses of a child’s image by evildoers, from tech companies and researchers stealing images to train surveillance systems, to companies recycling online photos into advertisements, to child pornographers, and

- unknowable future privacy invasions.

In brief, creating online content about a child can define their identity and digital citizenship without their participation. These threats go far beyond the ephemeral embarrassment of flipping through baby pictures in your parents’ living room. But I have no answer for how to address this issue, except that parents should think carefully before they share and remember that their decisions affect their children as well as themselves. For example, some parents deliberately post nothing about their children, while others disguise their children online, such as posting only nicknames and photos that don’t show the child’s face. Unfortunately, the Collinridge dilemma of not knowing whether and what to worry about—or how to prevent harm—applies to much of parenting, even beyond the ethics of sharenting.