Image: Claw Diagram from Japanese Patent CN 202497706.

“Claw machines are rigged.” This recent headline at Vox caught my eye. Not because it was surprising. But because it wasn’t. What I wanted to know was why someone was surprised to find this to be the case. There are a variety of interesting elements to be found in the post. Perhaps most interesting to myself and CASTAC readers, however, was an Also read link to an article drawing heavily on the work of Natasha Schüll and her wonderful book Addiction by Design. I had already assumed the game was rigged; I was surprised that anyone was surprised. But the term “rigging” gave me pause.

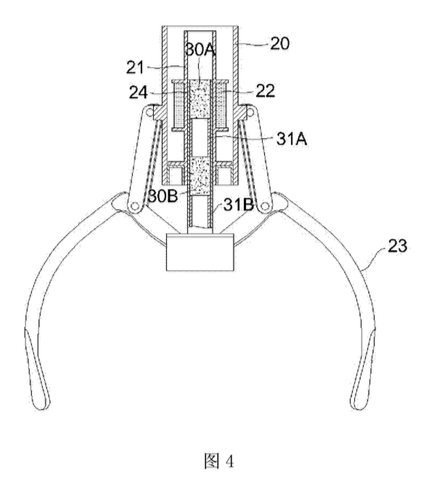

What I think surprised the author of this particular article was the way in which the game was rigged. It wasn’t that the claw just wasn’t strong enough, which had been my presumption up until reading the article. But rather that the underlying circuitry of the game dictates a variety of behaviors from the claw. All of which fall into some subset category of what we’d expect from a claw in a game machine. Sometimes the claw grabs harder than others. Sometimes when it grabs more tightly it “loses” its grip on the way to the drop zone. All of these are controlled by a desired payout rate dictated by the operator (i.e., owner) of the game. Which is why while reading the article I thought to myself, “that’s quite literally the same core mechanism that operates how the RNG (random number generator), discussed by Natasha Schüll, in a gaming machine functions.” Which is why I was then doubly pleased to find her work when I clicked the Also read.

But all of that prompted me to think about rigging. Because ostensibly this game of “skill” was “rigged” by the element of randomness being introduced in order to ensure that the machine generates revenue. Most coin operated games use “pinch points” in order to ensure that a player will encounter times in a game where skill alone will not save a player. Additional coins will need to be added. Of course that isn’t the case for early arcade machines; indeed most could be played forever or until they crashed if a player was skilled enough. So were those arcade games that came later rigged?

But the idea of rigging stuck with me. I started with a dictionary and found rigging is Scandinavian in origin, meaning to “bind” or “wrap up.” Much of the history of rigging was in nautical activities: sail boats have rigs. But cameras have rigs too. Computer systems are often referred to as rigs. There are oil rigs. Trucks can be big rigs. Sometimes one “jury rigs” or “jerry rigs” something. Indeed any kind of apparatus or assemblage could be a rig. So what separates a rig from something rigged? And I think Natasha Schüll’s book offers an answer that many anthropologists can take seriously. Many of us study assemblages. We study rigs, of sorts. In my book I call them “underlying systems,” but I might as well have called them rigs. I could imagine (because Jordan prompted me to) us thinking about infrastructure as rigged [Editor’s note: or rigging as infrastructure]. But asking the question of “to what end?” have these rigs been constructed in an important one. I think it is the kind of questions that anthropologists frequently ask themselves. These are increasingly important questions in a rigged world.

The issue of rigging is particularly crucial as we explore designed systems. As Schüll observes, sometimes rigs don’t work. Sometimes those rigs send people fleeing. The rigging of the system becomes discernible and when a “player” recognizes an undesirable rigging, sometimes they defect. But not always. Are all designed systems at some point rigged? At least in game design and development, I can guarantee that there are jerry rigs, particularly as projects come to an end. Perhaps that is one of the core elements of design that ultimately requires moments of bricolage to bring networks into submission.

Indeed the very idea of rigging comes from boats and sailing and the ability to re-work systems as needed, yet remain consistent enough that they can be reliable as well as learned. The very premise of the jury rig is the rig you need most when a ship is crippled. Rigs aren’t bad; it is their emergent experience that makes them so. And so, perhaps in switching from one sort of rigging for a claw-based game machine to the RNG over some other kind of rig did fundamentally change the game. But the claw machine was always about making money. It was never about the little toys in the box. But you didn’t know that. Until you did.

1 Comment

Very nice input about the word “rigging.” Not also sure how exactly it came to denote something that’s been manipulated to do something that it’s not supposed to do. Claw machines are frustrating because you simply cannot win with them as easily as you can, even if you have the skills.

1 Trackback