The sun comes up over Teziutlån, Puebla, Mexico (photograph by Roberto Barrios)

On the first days of October 1999, the city of Teziutlán, Puebla, Mexico, experienced levels of precipitation that tripled its annual rainfall. Throughout the city, a number of hillsides occupied by working class family homes reached a critical point at which upper layers of soil and environmentally degraded rock began to give way under the weight of accumulated rainwater and settlements, creating major landslides. The most dramatic of these landslides occurred in the neighborhood of La Aurora, where settlement and land use practices came together with geological history and environmental factors to create a massive movement of soil, trees, rocks, and houses that killed 109 of the 200 people who died in similar events throughout municipality that week. The catastrophe was deeply traumatic at the local level, leading to a period of mourning that overtook the city, and it also gained national attention, resulting in a visit of the devastation by then president Ernesto Zedillo.

A memorial to the Teziutecos who died in the 1999 landslides (photograph by Roberto Barrios)

The Aurora landslide site as it stands today (photograph by Roberto Barrios)

Following the landslide in La Aurora, Teziutlán has gained a reputation among local emergency management staff and national scientists as a unique laboratory for landslide research, experimentation with early warning systems, and other disaster mitigation practices like community resettlement. At the time of the disaster, the call to develop landslide mitigation practices and technologies in Teziutlán was the politically savvy thing to propose among state and federal politicians, but actual support for such efforts has lagged behind the expectations created by government press releases and public speeches. For the socially conscious geographers, emergency management workers, and engineers involved in preventing landslides in Teziutlán, on the other hand, the city has become exemplary of the challenges confronted by Mexico in an era in which increased climate change-driven hydrometeorological events are coming head to head with a 500 year history of human environmental relationships that have increased the likelihood of events like that seen in 1999. In September 2013, for example, the coincidence of Hurricane Ingrid and Tropical storm Manuel brought about similar catastrophic events throughout the country, impacting the states of Guerrero and Oaxaca, and once again causing the deaths of at least 200 people. In this blog entry I want to investigate the questions: What arrangements between humans and materiality are engendering conditions of landslide risk in Teziutlán, what arrangements between humans and materiality are imagined by disaster mitigation specialists as the solution to this condition, and what relationships between people and materiality are feasible in contemporary Mexico?

Catastrophes are events that take place in space, and space is not a neutral backdrop of human action, but something that emerges out of co-constitutive and meaning laden relationships between people and the material world. In this regard, Teziutlán is an exemplary case. The site where the city is located was chosen by Spanish colonial settlers for mining purposes because of the richness in minerals of the Sierra de Puebla. The locality where the city was founded was suitable for the size of the original colonial settlement, but was eventually outgrown over the course of mining and maquiladora development booms of the 20th century. The site lies on one of the major ridges of the Sierra de Puebla and extends from lower elevations in the north to higher elevations in the south. The city’s colonial center is located on top of the ridge, where there is no landslide risk, but the greater area of Teziutlán is characterized by a number of ravines that have been settled in a piecemeal fashion during the last 85 years.

One of the key figures in the history of Teziutlán is Manuel Avila Camacho, national president of Mexico from 1940 to 1946. Following political convention of favoring one’s region of provenance, Avila Camacho insured the execution of a number of mining development projects during the 1940s in the area. The boom featured a rise in population that began to push working class settlements into hillsides.

The mausoleum of the Avila Camacho family at the Teziutlån cemetery. The cemetery sits atop Aurora’s hillside and is suspected of playing a role in triggering the 1999 landslide (photograph by Roberto Barrios)

Additional development-related urban growth occurred between 1980 and 1990, when maquila manufacturing operations were expanded in the area. This latter regional development strategy also lacked urban planning initiatives that insured the settlement of working class neighborhoods in areas with limited disaster hazards, adequate social services, and affordable means of transportation. Consequently, since the 1930s, Teziutlán has seen a process of exponential population growth that has not been followed up by urban development practices that mitigate landslide risk. Working class families have populated landslide prone ravines that are close to the city’s center and maquiladoras, as these sites provide proximity to worksites as well as the city’s central market areas, where basic commodities are cheaper than in outlying areas. Resettlement projects like that of Ayotzingo, which was created as a response to the 1999 landslides have proven unpopular among working class Teziutecos as the site is mired by undependable provision of public services (running water is largely absent, for example), higher transportation costs to and from places of work, higher cost of basic commodities like food, and diminished size of housing structures and land parcels. Anecdotal accounts report that up to 50% of originally resettled Teziutecos have abandoned the resettlement site in search of better-situated places to live, even if these places are prone to landslides. Landslide risk, then, is a product of Teziutlan’s own success within a model of development that prioritizes capital gains and people’s participation in transnational commodity production processes as “cheap labor.”

On the fourteenth anniversary of the 1999 landslides, I sat down with the director of the city’s emergency call center, Octavio Salazar, a Teziuteco who has taken up the cause of reducing landslide risk. Octavio gave a grim assessment of the city’s strides toward landslide mitigation since the catastrophe, stating, “Our population has grown and landslide risk areas are still inhabited. If we get rain like we got in 1999 again, we will see an even bigger disaster.”

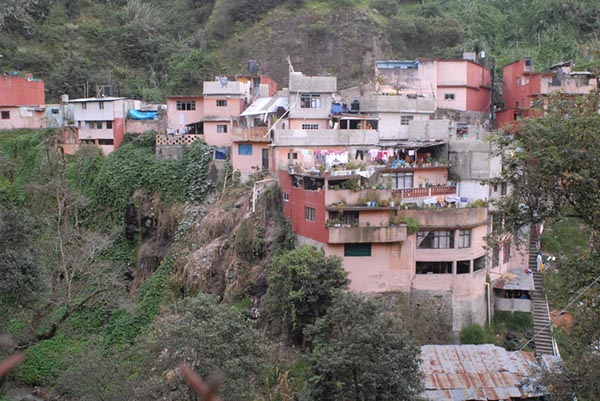

Colonia Juarez, a landslide-prone neighborhood in today’s Teziutlán (photograph by Roberto Barrios)

Evidence of recent affectations by storms Ingrid and Manuel in 2013 (photograph by Roberto Barrios)

In recent years, Octavio has been working closely with researchers, faculty, and students specializing on landslides from the department of Geography of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) and with soil engineers from the Mexican National Center for Disaster Prevention (CENAPRED). The work of these engineers and geographers has featured the installation of two monitoring stations that routinely measure ground water pressure, soil water absorption, soil movement, and precipitation levels. Their goal is to determine the role of these various factors in triggering landslides and also providing an early warning system during the rainy season. Something CENAPRED and UNAM researchers and engineers have quickly come to terms with over the course of their research in Teziutlán is that developing a landslide early warning system is by no means a process where clear demarcations between scientific practice, policy, society, and culture can be made and maintained. Putting together Teziutlán’s experimental landslide monitoring system has required an integration of relationships between researchers from various academic disciplines, emergency management personnel, local politicians, residents of landslide prone neighborhoods, soils, water, and electronic monitoring equipment.

These relationships are not a given and do not remain unchanged, they have to be made and re-invented at varying intervals, depending on the temporal scales of national and local politics, changing environmental conditions, and the professional lifetimes of academics and CENAPRED technicians. The result of this process of relationship making is a collective of human and non-human agency, subjectivities, social, professional and political interests that collectively make what techno-scientific disaster mitigation in Teziutlán is. The ontology of landslide mitigation in Teziutlán, then, is not a coherent entity whose existence may be taken for granted, but is a dynamic web of semiotic human-material relations that is ever-emergent where people and things can play key roles in shaping what it looks like, how it works, and how closely it approximates an ideal Mexico where disasters do not occur.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Dr. Irasema Alcántara Ayala and the UNAM Department of Geography for supporting this ongoing ethnographic project.