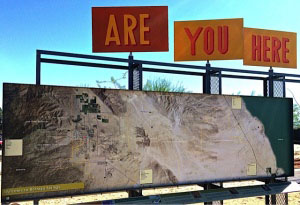

“Are you here?” asks a “satellite view” map in downtown Borrego Springs. Photo by author.

As of late October, nearly 60% of California faces conditions of “exceptional drought,” a category that the National Drought Mitigation Center refers to as indicating “exceptional and widespread crop/pasture losses,” with “shortages of water in reservoirs, steams and wells creating water emergencies”. Mandatory conservation measures are in effect across the state, and Governor Brown recently signed a Sustainable Groundwater Management Act that will tighten regulation of California’s notoriously under-managed groundwater supply.

I conduct my fieldwork in Borrego Springs, a small desert town in Southern California that has slowly become enmeshed in an envirotechnical regime of groundwater surveillance, drought mitigation, community engaged scientific research, and climate change adaptation. Nothing draws a crowd quite like a “wicked problem,” and I follow the network of community activists, scientists, and government agents that transform this town’s anticipated water shortage into a significant indicator of regional and global environmental challenges. Ultimately, this means that I’m following how water itself is scaled in the high stakes context of one of the worst droughts in California’s recorded history.

Refrigerator door inspiration at the Steele/Burnand Anza-Borrego Desert Research Center in Borrego Springs. Photo by author.

Most recently, I’ve had the privilege of working as part of “Team Water UCI,” a transdisciplinary research team of graduate students at the University of California, Irvine that represents an ongoing collaboration between water researchers at UCI, community leaders in Borrego Springs, and environmental scientists working with satellite data at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The Team Water project is driven by an interesting experiment in data sharing and integration. It proposes a way of incorporating JPL’s remotely sensed, big data view of water and climate into the same model with grounded measurements and cultural data on water use and environmental effects. In other words, this is a model that aims to question what water looks like globally, regionally, and locally, or perhaps from space, from the ground, and from underground.

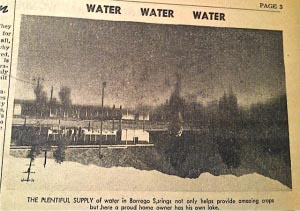

Localized plenty: a November 1951 article in the Borrego Sun newspaper boasts, “The plentiful supply of water in Borrego Springs not only helps provide amazing crops but here a proud home owner has his own lake”. Photo by Anna Kryczka, Team Water UCI historian.

As one of the advisors for the project noted, this quickly becomes a question of what words mean. If you say you’re studying something like water sustainability in an extreme environment, well, what counts as “sustainability,” “extreme,” or “environment” depends entirely on your perspective. When it comes to water problems, scaling is everything. Water presents certain challenges for mapping the relationship between micro and macro, local and global, past actions and present consequences. Its material flows and movement resist easy spatial boundaries, and its cycles of evaporation and precipitation verticalize the potential field of inquiry.

The inclusion of remotely sensed satellite data operationalizes a sense of manipulable scale in interesting ways. Ecological processes like droughts – based on changing material conditions within a given environment – become problems of water management that can be zoomed in or out, quantified, compiled, and archived. Droughts-as-data can haunt predictive models as potential future crises; they can be prevented or managed before they even “occur”, and they can fluctuate between meaningful categories like “exceptional disaster” or “new normal”.

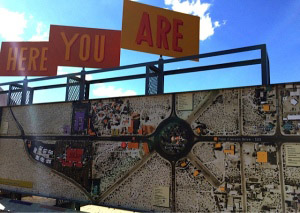

“Here you are,” answers the zoomed in map of the downtown area on the other side. Photo by author.

Scaling solutions for these water problems is not about identifying a global hazard and meeting it halfway through regional or local interventions, but rather of thinking critically about how and for whom that scaling is enacted in the first place. Team Water started our first meeting with a simple question that has since become our primary provocation: how do we define this place? If we follow the limitations of our respective data and disciplinary approaches, we quickly run into mismatches and noise. Our baselines and time points are different. The satellite’s view from space is coarse when compared to the finely-tuned human’s view from the ground. We recently spent almost 20 minutes staring at a satellite image of the Borrego Valley, tracing our fingers over the computer screen to demonstrate the different ways that each of us would draw the boundaries of this water-based ecology.

Sometimes, however, in the process of examining just where these differently scaled perspectives emerge, the mismatches become interesting opportunities for compatibility without comparability, and a cyborg research question emerges. From my anthropological perspective, this ground up approach to the politics of data and the building of research projects raises some compelling lines of inquiry on the science of team science, and the impact of “broader impacts.” Global and regional data on water insecurity carry weight in the policy world, driving the architecting and implementation of local sustainability solutions from global experts (witness the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, above). At the same time, there is a powerful politics of “being here” at work in Borrego Springs (as elsewhere); there is a privileging of local expertise and intimate familiarity with local daily life over the view from above. How then is the significance and scale of a water problem created locally vs. from a distance? Can the two ever meet? Where and how must data be collected to yield the most useful information, and for whom? As we go forward, my hope is that Team Water’s exploratory stance will keep forcing us to reconsider the taken-for-granted spatial and temporal scale of water as a managed object, and help us find new ways of working with the view of Earth’s water from space.

1 Comment

Thanks for sharing this post. Interesting case study.

Any sense of traditional water management among indigenous populations, co-adapted over centuries, e.g., ala Lansing’s work with Balinese Water Temples, and Stoffle’s similar work with Paiutes? This presents an interesting epistemological issues for ‘what are data’ and whose data count at what scale. The Bali case is particularly instructive: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h9ozS8BKUFI