Image: Layers of dead fish and desiccated barnacles at the shores of the Salton Sea, a man-made salt lake maintained by agricultural runoff. Photo by author.

This March, California’s State Water Resources Control Board called for a public workshop to re-evaluate the state of the Salton Sea, a complex and notoriously disastrous salt lake in the southeastern California desert. Nearly 200 people responded to the call, crowding in to a hearing room in downtown Sacramento to give testimony on mitigation and restoration projects, consider drought impacts, argue for the Sea’s environmental and economic value, and discuss the enormous water transfer agreements that threaten to damage it even more. Attempts to define the problem and its stakes have gone on for decades, but it is still far from clear whose fault is it that the Sea is still shrinking, still dying, or still dangerous, or, for that matter, if anyone can (or should) keep trying to fix it. As a semi-permanent disaster landscape, the Salton Sea is best defined not by the fall-out from a singular event nor by the slow accumulation of risk, but by a decades-long dynamic tension between mitigation of danger and restoration of health. “SOS! Save Our Sea!”, a popular slogan of local activists, is both a call to account for an irreversibly toxic present, and a reminder that the Sea was and still is a vibrant place worth saving.

Image: In the front row of the audience, high school students from communities around the Salton Sea hold up signs readings “SOS!” and “Save Our Sea!,” positioning the signs so that Water Resources Control Board members can see them. Photo by author.

John, an environmental justice activist seated to my right, helps me interpret the history of disaster politics playing out in the room. The crowd has even separated itself according to profession and position, he says: water agency directors and businessmen to the right; community organizers and environmentalists to the left. The technical arguments about legal obligations, water transfers, and public health statistics provide a bird’s eye view of the incredible work required to maintain large-scale, long-term mitigation. But John reminds me they also reveal the uneasy scientific and cultural politics of a hydraulic society trying to combine that mitigation with renewal and restoration.

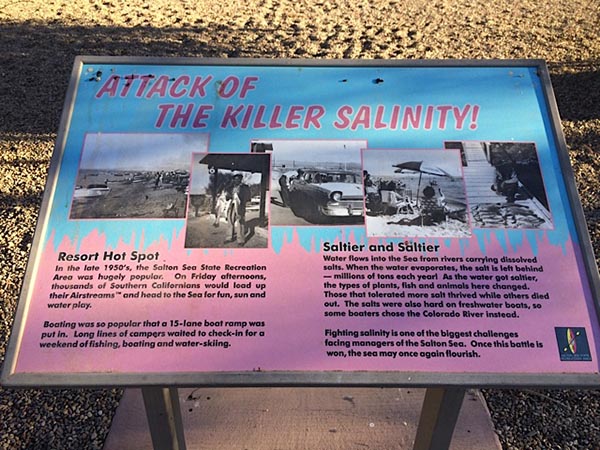

Image: A placard at the Salton Sea State Recreation Area explains the transformation from “resort hot spot” to salt lake. Photo by author.

The Salton Sea’s history of boom, bust, failure, and rescue is a century long. During the desert agricultural boom of the early 1900s, engineers for the California Development Company built a series of canals to irrigate the Imperial Valley with water from the Colorado River. When outflow from the river overwhelmed the canal system, water filled the dry lake bed at the Salton Basin, (re)creating a modern-day lake. As water levels stabilized, the Sea enjoyed a brief mid-century heyday as a popular resort area, drawing tourists to boat, swim, and fish in the middle of the desert. Over the following decades, however, continued evaporation and water flows saturated with sewage, agricultural chemicals, and salt made the Sea poisonous for most wildlife and potentially dangerous for humans. Tourists left, property values collapsed, jobs evaporated, and plans to “save” the dying Sea began circulating in earnest.

Image: At the shore of the Salton Sea, a road divides two very different views. On one side, blue water and bleached trees captured by countless nature photographers; on the other, one of many geothermal plants that promise clean energy and local jobs. Photo by author.

The Salton Sea today is an ecological oddity, both productive and precarious, hostile and hospitable. Its waters are maintained by a delicate network of rivers, agricultural runoff from surrounding farmlands, and drainage systems, all combining to mitigate the impacts of natural evaporation and keep the harmful materials in the lake bed buried under water. It is a tremendous habitat for over 400 species of birds, but is known more for its macabre beaches of fish and barnacle bones, photogenic suburban “ruins,” and the sharp briny smell that rises from the water.

Image: A system of canals irrigates the agricultural lands surrounding the Salton Sea, flooding plots to flush out salts, and eventually feeding in to the Sea itself. Photo by author.

Debates over what kind of problem the Salton Sea represents have taken on heightened urgency today. In 2003, before California’s current “exceptional drought” began, the Imperial Irrigation District (which serves the Salton Sea area) signed an agreement to transfer some of the Colorado River water currently flowing to farms in the Imperial Valley (and, via agricultural runoff, to the Salton Sea) to other water agencies, and specifically to thirsty urban centers like San Diego. The Imperial Irrigation District agreed to provide fifteen years of “mitigation flows” to slow the impact on the Sea, while the State would use those same fifteen years to support a simultaneous restoration effort bringing the Sea to a state of sustainability. The public workshop in Sacramento was called in response to the imminent end of the mitigation flows in 2017; the tipping point at which many Salton Sea activists say “we fall off the cliff.”

Image: A sign warns residents not to risk contact with agricultural runoff flowing through one of the small rivers feeding the Salton Sea. Photo by author.

Fifteen years of holding open that space of mitigation/restoration in a place already known as a semi-permanent disaster zone results in a mix of hope and frustration. Speakers slip between practiced technical and affective language to describe the hazards of exposed lake beds, airborne agricultural chemicals, and disappearing industries, ending with calls for the State to intervene so that one of the many plans already on the table can finally move forward. Of course, it’s not that simple, and again John offers commentary. If the stakes involve competing interests from farmers, farm workers, renewable energy developers, water companies, school children, seniors, asthma sufferers, birds, fish, and even global climate, then what (and whose) Sea are we trying to save? Will we ever finish saving it?

Emily Brooks is a Ph.D. student in Anthropology at the University of California, Irvine, and a Graduate Research Associate with the Steele/Burnand Anza-Borrego Desert Research Center. Her dissertation project investigates the science and cultural politics of slow ecological disasters through a focus on water scarcity, climate change, and applied environmental science in the Southern California desert.

6 Comments

I would like to quote and and use some images from this post for a series of articles our art foundation is doing to support the SOS cause and promote the work and message of artists and musicians who are trying to draw attention to the issue.

Our chief inspiration for this is the recent and ongoing work of a local, but now internationally known, artist named Christopher Cichocki (pronounced: seh-shaw-skee) and his invitational artist residency program known as the Epicenter Projects. His work focuses on the transient nature of our world and specifically the transition of this valley from ancient sea to modern desert. The intervention and damaging side effects of industrial proliferation and the necessity to rectify the results of it is a central component.

Christopher is an avid supporter of Save Our Sea and all efforts stabilize this toxic situation and restore sustainability. We hope to be able to work with him to connect other artists and creatives and mobilize a media-driven campaign to “shake the trees” for funding of significant restoration projects.

Our website is at http://www.ArtFoundationDHS.org

Our organization is the Art Foundation of Desert Hot Springs, CA. We are similarly economically challenged city that was once a hot tourist destination. We have retained a healthy tourist trade due, ironically, to our award winning healing water from underground aquifers. However, all other commerce and industry has dried up and vacancy and blight are the challenges we face. But our problems seem trivial compared the environmental time bomb looming over the communities surrounding the lake.

We feel a kinship to the municipalities and unincorporated areas afflicted with fallout from this ecological disaster site, and we wish to join the fight by connecting more artists, musicians, and arts administrators capable of directing funding and public attention towards the cause.

In addition to the article series, we want to create a informational hub page with links to all the different players in the activist, science, political and creative communities involved with the issue.

Please consider granting us permission to reuse this and any other content you think may be appropriate or helpful. Any other suggestions or comments are also quite welcome.

Thank you for your time.

Brown Miller

Media & Technology Director

Art Foundation of Desert Hot Springs

BMilller@ArtFoundationDHS.org

760-905-2116

Pump ocean water in to keep level at current or higher level. Extract lithium,geothermal energy production responsibly and to sustainable level (do not lower lake level to access more resources). Install solar and wind power generation systems on currently available land. Stableize any exposed hazardous land. Stop pollution in and allow natural water runoff in without being confiscated and sold off for profit. Clean up and make lake responsibly accessable for human use/recreation as well as being once again a source of sustenance for wild life. Above mentioned actions will pay for the restoration as well as generate revenue for the state and local government. This will also eliminate the pending potential environmental disaster. This is a win win solution for all as well as being economically fesable and just the right thing to do morally and ethically.

Just do the right thing without inter departmental bickering.

I live in Tustin Cal. (Orange County)

25Mill people live in Southern Calif.

We all need save our sea.

I suggest that

Every month add a $1.00 Salton restoration fund (tax) onto every single water bill in southern cal.

Or better yet make it $2. per mo.

I would be more than happy to pay the extra $24. a year to help restore the Salton sea over time.

$25Mill dollars collected each month? WOW!

I cannot imagine anyone complaining about that.

Sincerely

Single Low income mom from Tustin Cal

Just watched American Rivers.

Folks by the Salton Sea…make lemonade !!

The wind is blowing ..windenergy! The sun is shining …solar ! Floating on the surface on pontoon platforms it reduces evaporation. Make them with long tether and anchorlines, to move a bit every week, so that sunlight still gets to the bottom. If on land , the arrays can be on the wide poisonous beach, maybe keeping it from blowing so much . Also plants are available for salty ground, dry or marshy, to keep it all from dusting the air. Plants will eventually help to keep moisture in the ground , the green cover might improve your microclimate ! Don’t just sit there !! Help yourself and help the planet !

Though I live in Michigan I am connected to Salton sea by a 20 acre parcel just south of Bombay Beach that I own jointly with my sisters and has been in our family for more than 50 years. Complicated reasons why we’ve hung onto it, but we would love to see it become useful to the restoration of the Sea and surrounding area. Is there anything in conjunction with our property that we can contribute to the ongoing efforts? I notice many of these posts are a few years old. I will continue looking for more recent posts and other activity.

Being in a state with lots of fresh water and with our own protection and preservation issues, I understand the importance of protecting the water for the life and spiritual restoration of the planet. Thanks to all for all you do.