A month ago, global science news was abuzz with the addition of a new ancestor to our human family. The revelation of the discovery and recovery by paleoanthropologists of more than 1,500 hominid bones belonging to the new genus Homo naledi from a South African cave was momentous. And while the discovery may be of interest to CASTAC Blog readers simply as anthropological news, what I think makes it particularly germane to our ongoing colloquy is how the research was planned and conducted and how news of the discovery was disseminated by digital means. From FaceBook to Twitter, from digital imaging to scientific visualization, and from National Geographic to eLife, the pervasive use of digital technologies and social media in the project made possible the acceleration of an extraordinary scientific discovery that is already challenging established paleoanthropology dogma. The tale of how Homo naledi went from cave to rave is intriguing, but the story behind the story, of how the digital practices the researchers used stand to become the modus operandi for future projects, is even more so.

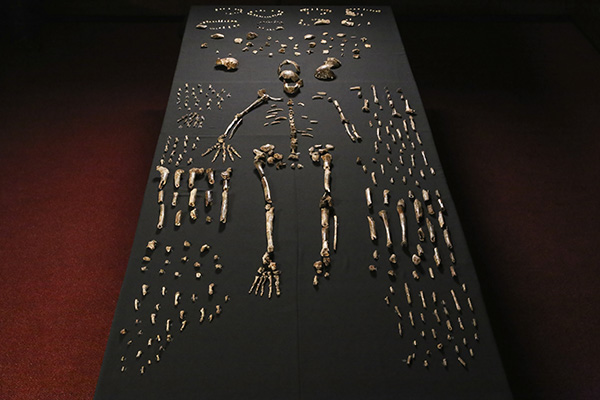

Image: Skeleton of Homo naledi in the Wits bone vault at the Evolutionary Studies Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. Photo by John Hawks/University of Wisconsin-Madison. Photo courtesy of the University of the Witwatersrand.

Rising Star

The story begins with the discovery of the Homo naledi remains deep in Rising Star, a cave in the limestone cave ecosystem of the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site that is so tortuous, only the lithe should enter. In September 2013, two cavers venturing into a previous undiscovered part of the cave where they descended a forty-foot-long chute, that was in places less than 8 inches wide, to find a bone filled chamber. Sensing the implications of the find and not wanting to risk compromising the site, the cavers took only digital photographs of the fossils and left. Those images became the first digital product of the Rising Star project, with many more to come.

By early October 2013, the cavers had taken their photos to Lee Berger, a paleoanthropologist at the University of the Witwatersrand, who used them to secure research funding from the National Geographic Society. In a matter of days, Berger was using FaceBook and LinkedIn to recruit the slim, agile paleoanthropologists he needed to traverse the cave and professionally excavate the remains. Interviews of candidates from around the world were conducted using Skype, as email, texts, and tweets carried news of the job and, eventually, offers of employment. By early November, a skeleton crew of strangers was converging on Rising Star.

Once the expedition began, National Geographic videographers followed the archaeologists into the field and down into the cave. Each day, the all-female excavation crew brought hundreds of fossils up to the surface: long bones, ribs, pieces of skulls, jaws, and teeth along with fully articulated feet and hand bones. Homo naledi quickly became the most fully represented paleo-human ever discovered at the Cradle of Humankind site. Daily blog posts from the field recounted not only the cave’s treacherous and difficult working conditions along with each day’s discoveries, but served to keep the laboratory analysis conversation going long after the two-week excavation ended.

Image: The paleoanthropologists who performed the excavation are pictured near the entrance to a series of limestone caves known as Rising Star near Johannesburg, South Africa. Photo by John Hawks/University of Wisconsin-Madison, courtesy of the University of Witwatersrand.

When the recovery was over, Berger again took to the ‘net. Making no bones about wanting to open up the field of paleoanthropology to a younger generation, he put out an online call in March 2014 for research applications specifically from early career scientists willing to study the fossils at a workshop held in Johannesburg. The deed proved to be a bone of contention among the ruling paleoanthropology patriarchy as such important finds were normally reserved for senior scientists, but it earned Berger the title Mr. Paleodemocracy as the young scientists were recruited online to study Homo naledi.

Using data from lidar scans, high-resolution digital photos, and the fossils themselves, the scientists created computer visualizations that filled in information missing from the Homo naledi skull. They ran the visualizations to 3D printers to make exact copies of the bones that could be handled. Eventually, a forensic face reconstruction expert used the 3D models to put a face to our ancient cousin.

After eighteen months of more study and analysis, it was time to publish. The scientific paper, which in previous decades past might have been otherwise published in the world’s premier scientific journals of Nature or Science, was published in eLife, a burgeoning, open access, and peer-reviewed journal that covers the life and biomedical sciences. eLife also posted an audio interview with the paper’s authors as a podcast. Synchronous to the paper’s academic debut was the joint PBS-NOVA/National Geographic television broadcast of Dawn of Humanity, which was later streamed on the PBS website. Millions watched the discovery unfold. Video coverage of the official news conference held in South Africa announcing the discovery was streamed from the event and today sits on YouTube, digitally marking the historic event.

Not your father’s (or mother’s) paleoanthropology

So what does this all mean for the anthropological study of paleoanthropology science? Clearly, the ways in which digital technologies and social media were used to bring Homo naledi to light were extraordinary, perhaps even revolutionary, as the ways in which Homo naledi was discovered, retrieved, studied, and introduced to the world differs substantially from the way in which most paleoanthropological science is conducted. It is perhaps apropos that evidence of a possible evolution in the practices of anthropological field science would come to light in such a traditionalist discipline, where it would be so very conspicuous.

Ultimately, the case creates for me more questions than answers. Was this simply a manifestation of idiosyncrasy: a unique convergence of digital technology and social media that is unlikely to reoccur? If not, what kind of impact will digital technologies and social media have on the future practices and communications of paleoanthropology? Or on archaeology? And will these new ways of making discoveries, hiring staff, creating scientific collaborations, recruiting students, capturing, processing, sharing, and analyzing data and publicizing research results have broader implications for the practices of science in other fields, both outside and inside the laboratory? Are the scientific communities I study (or studied only a few years ago) already changing in response to these transformative digital forces? At this point, the answers elude me, but seem nonetheless worthy of serious study.