Poster for the film The Human Face of Big Data. Copyright 2012 Against All Odds Productions, reused with permission.

“Is Data Singular or Plural?” I googled as I sat down to write this post. In my dissertation on the Quantified Self movement and the types of subjects produced by the collection of personal data, I had all but taken for granted that the word ‘data’ has become a singular noun. “Data is” announce countless articles and industry conference sessions putting forth definitions of personal data as a shadow or footprint, digital double or virtual copy. My advisor patiently suggested that I check my grammar.

Turns out my mistake, at least, was not singular. Derived from the Latin dare, meaning “the givens,” grammar and history instruct us that ‘data’ is the plural form of the singular ‘datum.’ Alexander Galloway has helpfully noted that the word’s original plural sense can still be read in the French translation of data as “les données.” In recent years, however, the proper usage of the word has become a topic of some debate as data has been increasingly employed as a singular noun. What can this shift towards the singularity of data tell us of the operation of personal data in popular thought?

Only a few years ago, The Guardian asked: “Data are or data is?” resolving to accept both uses because increasingly everyone does. And Forbes had likewise questioned “Is the Word ‘Data’ Singular or Plural?” “Many people are in quandary” about whether data should be treated as singular or plural, announced an Oxford Dictionaries blog post intent on settling the confusion, in the end deciding that popular rather than proper phrasing would adjudicate so long as one remained consistent.

Etymology isn’t law. Language moves, it perforates rules. Rationalizing the shift, grammarians have explained that today the usage tends towards the singular because of a common confusion: as a term of Latin origin, the ‘a’ at the end of the word appears an unnatural plural to English-speaking ears, inciting would-be users falsely to deem it singular and so meeting the fate of other Latin imports like ‘agenda’ or ‘stamina,’ and often ‘media’. Or otherwise data as a mass noun rather than as a count noun permits this substitution. Moreover, as the general knowledge of and reverence for Latin has itself abated, so has the consistency of Latin’s use. The Merriam-Webster dictionary has thus taken a more decisive populist position. Offering a secondary definition of data as specifically computerized information—“information that is produced or stored by a computer”—and not just a synonym for ‘facts,’ it advises that today, “data leads a life of its own quite independent of datum, of which it was originally the plural.” Assuming the haughty tone of a teenager scoffing at her parents’ dated ways, the dictionary contends that the remaining plural construction—if used at all—is nothing but a relic, “an anachronistic pandering to fading tradition… more common in print, evidently, because the house style of several publishers mandates it.”

Though slip-ups persist ever since the word’s entry into the English language some centuries ago, ‘data’ has largely been employed as a plural throughout its technical and editorial history. The term’s singular identity has only recently entered wider debate just as its general usage escalated in direct proportion to the term’s widening circulation and use in connection with a growing array of data-producing digital tools. The articles I came across pondering the question of data’s identity all date to 2012. That since the question appears less frequently posed is itself indicative of the possibility that data has settled into its contemporary singular form. Vagaries of grammar not withstanding, why has it become unnatural, pretentious, and simply outdated to utter data in the plural?

The age of Singularity

It is interesting that the term appears to have dropped its pluralist pretensions precisely in the age that Silicon Valley futurist Ray Kurtzweiler has hyped as fast approaching a radical Singularity, a decisive moment when a compendium of knowledge, ushered in of course by massive quantities of information, will come together into a singular machine intelligence too great for humanity (taken as a whole) to process. In fact, it is the image of data’s radical singularity that has given the term ‘big data’ its cultural force. The term seems to telegraph informatic unity, commonly understood as an epic aggregate of discrete parts tending towards ever larger, singular forms. Mirroring the cohesive properties of data, the reporting on the contemporary data ‘age’ is often itself conceived as a singular event—as an explosion, a deluge, a revolution, a big bang.

Debates over data ‘access’ and the popular imaginary of ‘open’ data are likewise overdetermined by notions of data as something unitary and concrete to be linked or networked together into even greater wholes. Echoing this view of a seamlessly connected data set, a CEO at a wearables conference I attended recently quipped, “data is an opportunity to get a more holistic picture of our users… Imagine a world where we can correlate weight, weather, nutrition, environment. That is where I see the value of big data… to really get a more personal look at the user.”

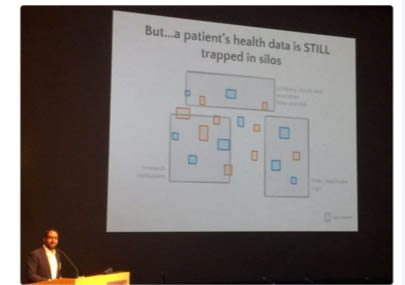

Impediments to data’s movement towards totalizing wholes are thus often seen as barriers to be transgressed. The woeful lack of technical standards that still preclude connections between data sets has, as rule, become for many developers a matter of serious consideration and concern. Similarly, in public data advocacy, breaking down the political and institutional infrastructure that keeps data locked in ‘silos’ and in separate hands has surfaced as a pressing issue to be explored.

Presentation on the different ‘silos’ in which data sits, at the 2016 Health Data Explore conference. Photo by author.

Overall, in a technical environment that agitates for greater ‘interoperability’ between data sets, plurality has come to stand for the needless duplications of effort that could be eliminated with data sets that travel from place to place without institutional borders or boundaries. Plurality increasingly represents the chaos of multiple standards that leaves information locked in ‘silos’ and keeps fruitful integration and cross pollination at bay. Plurality has thus become a technical problem to be solved or a political challenge to overcome.

A totalizing view from outer space

Contemporary wearable and Internet of Things (IoT) technologies are often marked by a hackneyed cosmic sci-fi aesthetic, as many have noted. More than a form of nostalgic futurism, however, the association between contemporary sensor technology and outer space offers another way to grapple with the contemporary ‘singularity’ of data.

Take, for instance, the marketing materials of the Consumer Electronics Show (CES). In 2015, this annual technology showcase, the largest in the nation, welcomed its 160,000 attendees in Las Vegas with massive banners that directly referenced the familiar iconography of the by-gone Space Age, while the online ads were set against a star-studded background of galactic nebula.

CES 2015, photo by author; banner ad display at the CES 2015.

Or the Qualcomm X Prize, for which telecom giant Qualcomm will give away a $10,000 million prize in 2017 to the first company to develop a real life ‘Tricorder,’ a medical body scanner that is meant to “accurately diagnose” 13 conditions at the wave of a hand, inspired by a device of the same name used in the popular sci-fi series Star Trek.

Qualcomm’s Tricorder Prize. Via Catalyst Review.

Galactic imagery is invoked even in the vocabulary, particularly in technical fields, that narrates business success in aerial terms. A project that goes well is said to have “taken off” or to “skyrocket.” When discussing budgeting and resources, investors and business developers often speak of having enough “runway”—capital—to “launch” a business, as though a startup is itself a spacecraft being shot into the air, the brightest becoming “stars.”

Note, too, the choice of the airport as a favorite site for advertisements of wearable technology, IoT platforms, and data integration solutions. As I travel for fieldwork, I never fail to encounter expansive posters gloriously stretched through the airport’s main halls.

Ads for data processing software and wearable technology in San Francisco and Denver airports. Photos by author.

Allusions to space-travel in these instances perform the work of the air-pump in Bruno Latour’s analysis of nineteenth century laboratory science. Writing about the air-pump invented by Robert Boyle as a model of the modern laboratory, Latour drew force from an explicit parallel between the air-pump, as a space without air, effectively without atmosphere, and outer space. The air-pump, in other words, announced the kind of science that saw itself as at once in the world, outside of it, and also above it, reflecting the broader scientific rationality that increasingly interpreted and shaped the world all the while pretending to hold it at a distance.

In the same way, the contemporary cosmic aesthetic of data and sensor technology encodes a certain positivism at the level of form. Associations between outer space and sensor technology register the removed, neutral, and objective authority of devices all the while reducing the data produced to an observable, disinterested, and singular phenomenon which one can regard in totality, as if from above. “Data is knowledge derived from a height of 10,000 feet” an interlocutor had explained to me once. It is worth pointing out that it is precisely aestheticizing data as a perspective from a great height, like an aerial shot rather than its actual fact, that lends data its representational authority.

A whole in one

It’s not only good old positivism recast in data science clothes at work in the image of data that refers to outer space as its model. Also at play is the command-and-control infrastructure of computer-controlled nuclear technology that emerged in the wake of the Cold War, and which precipitated seeing the Earth as a singular closed world. The sense of the world as a knowable and manageable whole inflects the political lens through which the the famous photographs of earth as a “Blue Marble,” taken by the Apollo 17 crew in 1972, can be viewed.

Blue Marble earth photograph. Source: NASA.

For the readers of the Whole Earth Catalog published at the height of the Space Age by Stewart Brand, for example, the earth seen from outer space emerged as the paper’s central visual mnemonic, serving as a key bridge linking together notions of technocratic and social unity. “In the Whole Earth Catalog,” writes Fred Turner, “cold war technocracy itself had granted its opponents the power to see the world in which they lived as a single whole” (Turner 2006:83). This conceptual unity, Turner argues, helped later foreground the invoked community of the World Wide Web.

The Blue Marble earth, however, also implicitly endorsed the cultural relativism that an entire generation of anthropologists and sociologists had previously advanced for some time. Arguing against a universal theory of culture, theorists from Bronislaw Malinowski to Clifford Geertz nevertheless cast the world as a variegated whole united in difference. This is the same sense of cultural relativism that was later reproduced in the notion of American multiculturalism, which touted national diversity as a ‘salad bowl’ of distinct but integrated parts.

In the halo of this galactic imagery, the contemporary iconography of data likewise advances a notion not only of a unifiable self, but of a singular humanity that can conceivably become rendered as a commensurable data set, pointing to a ‘salad bowl’ of difference that can—albeit with effort—become assembled together into a variegated but coherent whole.

Since the height of cultural relativism, political philosophers and social theorist have of course argued that difference cannot be easily brought together or made commensurate. Not only is there rhetorical power in allowing differences of opinion to surface, as Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe argued some time ago, but as a wide body of work has since explored, the power dynamics underwriting images of cohesion and translation undercut any easy assembly of difference into equitable, continuous, or seamless wholes.

What the contemporary discourse on data suggests, however, is that where data today largely operates in the singular—as a mass noun—the plural has no place. Difference is too often understood as ‘bias’ to be eliminated or corrected in the quest for greater ‘accuracy,’ or as ‘friction’ to be smoothed out. In the moment of data’s singularity is it becoming increasingly more difficult to conceive of data’s inherent variability in ways that can not easily be linked together or niftily summed up? What would it mean—and what would it take—for data to become plural once again?

2 Comments

I really like the conclusion that we need more variability in data concepts. Here is a footnote from my 1995 dissertation on PET scanning where I also ran into an advisor who insisted data was plural: A few datums on data:

“The word ‘data’ is a queer fish. It is an English word formed from a Latin plural; however, it leads a life of its own quite independent of the English word ‘datum’ of which it is supposed to be a plural. Ordinary plurals can be modified by cardinal numbers, but data is not… Datum incidentally is a count noun; in one of its senses it has a plural, datums, which is used with a cardinal number (three datums).”

So begins the entry for data in Merriam Webster’s *Dictionary of English Usage* [1994]. The problem with data is that in addition to being a plural noun, it is also “mass noun,” like information or water. These nouns take singular verbs and require quantification (an ounce of water) and are otherwise indeterminate (this water). Data has been in use in the U.S. since the turn of the century, and has always been used with both singular and plural verbs (This is great data! These are great data.), yet “the plural construction is more common in print, evidently because the house style of several publishers mandates it.” Online *Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary 10th Edition* [1994]. Debates on its proper use have raged in the pages of *Science* as well as in style manuals. An informal survey of six dictionaries available for purchase at a local bookstore yielded two insisting on the plural construction, two offering both as equally valid, and two waffling. At one point, Evans [1957] *Dictionary of Contemporary Usage*, pointed out that different sciences used data in different ways. PET researchers, as the quotations in this dissertation reveal, apparently are unified in treating data as a mass noun taking a singular verb. This is both a convention in their multiple fields and I believe a result of their dealing with radioactive data which is *stochastic* in nature and therefore is only meaningful in rates and it might even be considered improper to call each decay a datum. As I am much more comfortable with this use as well, and as my publishing house currently does not mandate a proper usage, data will be used with singular verbs.

Thanks for the comment Joe and the helpful footnote!

2 Trackbacks