Editor’s Note: Today, Shreeharsh Kelkar brings us the inaugural post in a new series on Fake News and the Politics of Knowledge. The goal is to tackle the knowledge politics of both so-called “fake news” itself and the discourse that has cropped up around it, from a wide range of theoretical perspectives on media, science, technology, and communication. If you are interested in contributing, please write to editor@castac.org with a brief proposal.

Donald Trump’s shocking upset of Hillary Clinton in the 2016 US Presidential Election brought into wide prominence issues that heretofore had been debated mostly in intellectual and business circles: the question of “filter bubbles,” of people who refuse to accept facts (scientific or otherwise), and what these mean for liberal democracies and the public sphere. All these concerns have now have coalesced around an odd little signifier, “fake news” [1].

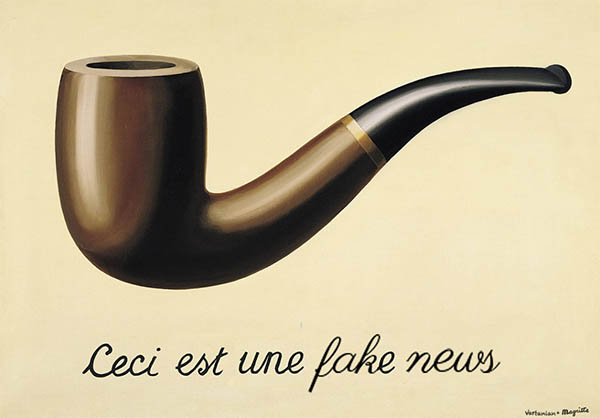

What is this thing called fake news? Photo Credit: Hrag Vartanian. CC BY-ND 2.0.

In this post, I want to think through the kinds of explanations of fake news that (liberal, mainstream) media establishments have drawn on as they attempt to both, cover the controversy, and explain it to themselves and to their readers. My own (unscientifically sampled) reading of (liberal, mainstream) media sources, suggests that they are using three types of explanations: (1) a pessimistic one rooted in evolutionary psychology that sees the Enlightenment as essentially wrong about human reason, (2) another rooted in more US-oriented, empirical studies of what social psychologists call “motivated reasoning,” and finally, (3) and a third, more institutionalist explanation that implicates the US media ecosystem itself. This third explanation, I conclude, points to another way forward, which is to reconceive what “objectivity” in the news media might mean in the future. This is a “wicked problem,” for sure, but could be something that STS could speak to.

Elizabeth Kolbert’s article written for a February 2017 New Yorker issue is of the first kind. It comes with the title “Why Facts Don’t Change Our Minds” and the subtitle, “New discoveries about the human mind show the limitations of reason.” It is a review of three books (“The Enigma of Reason,” “The Knowledge Illusion,” and “Denying to the Grave”) written by philosopher-psychologists. (And in what follows, I will be committing another cardinal sin: write about a book review without actually reading the books themselves. Since my focus is on the media coverage, I’m hoping that this will pass muster.) The review itself is couched almost entirely in terms of giant abstractions: mind, fact, reason, science, evolution. The explanation goes something like this: human reason was an evolutionary adaptation to humans’ “hypersociability.” The problem it solved was not understanding something about the world but the winning of arguments: how to make one’s own (or group’s) explanation sound more plausible in the face of other-group opposition (because it serves one’s interests). This explains for Kolbert why some people choose to read and circulate news items that can only be described as wild and in the realm of the impossible: loyalty has trumped reason. Surprisingly, for a piece written for a US audience, no mention is made of rising political polarization, the fractured media ecosystem, or even the rise of curatorial platforms like Facebook.

Even more surprising is the article’s almost overt endorsement of an evolutionary-psychology paradigm to explain fake news, something I would assume the New Yorker would be hesitant to embrace if the topic was, say, an explanation of gendered behavior. Here is Kolbert:

This lopsidedness [of study participants who continued to believe their own theories even after they’ve been told that they are mistaken], according to Mercier and Sperber, reflects the task that reason evolved to perform, which is to prevent us from getting screwed by the other members of our group. Living in small bands of hunter-gatherers, our ancestors were primarily concerned with their social standing, and with making sure that they weren’t the ones risking their lives on the hunt while others loafed around in the cave. There was little advantage in reasoning clearly, while much was to be gained from winning arguments. [my emphasis]

Of course, as with most explanations that draw on our ancestor “hunter-gatherers,” this one too cannot explain variation. Why is climate denialism a thing among US conservatives and not European ones? No explanation of “reason” as an evolutionary adaptation can account for this sort of variation, which has to be grounded instead in particular histories of science, environmentalism, regulation, and the state in the US and Europe respectively.

A second kind of explanation draws on a more empirical tradition of social psychology and political science (example this and this). The go-to concept here is “motivated reasoning” and researchers like Brendan Nyhan and Dan Kahan have performed a series of fascinating experimental studies to probe when exactly people change their minds. These researchers start from the premise that not all beliefs are equally important; rather, beliefs that are crucial to one’s self are the ones that lend themselves most to motivated reasoning. Their explanations therefore can account for the complicated history of the relationship between science and politics, across multiple institutional contexts. Studies like these bring up observations such as “[h]igh levels of knowledge make someone more likely to engage in motivated reasoning—perhaps because they have more to draw on when crafting a counterargument. These findings sound commonsensical but they also make for fun reading especially in the context of the ingenious experiments through which they are produced.

Personally, I find this strand of research fascinating, but things reach an impasse when the researchers are asked for a solution, and they admit that they have none. In their experiments, the researchers often try out a technique that social psychologists have developed in other work for example on dealing with stereotypes and discrimination: thus, when study respondents are asked to write self-affirming essays before they make decisions or evaluate facts, the decisions they make often turn out to be (statistically) significantly different. But these techniques—while useful in an experiment—are hard to fit into everyday contexts of media use. Thus:

Still, as Nyhan is the first to admit, it’s hardly a solution that can be applied easily outside the lab. “People don’t just go around writing essays about a time they felt good about themselves,” he said. And who knows how long the effect lasts—it’s not as though we often think good thoughts and then go on to debate climate change.

A third explanation comes from political scientists interested in the study of American polarization but this research, as far as I can tell, doesn’t seem to make it into much media discourse (This lengthy Vox piece uses it to great effect but doesn’t take it far enough.) In a fascinating summary of their book Asymmetric Politics, Matt Grossmann and David A. Hopkins lay out a compelling story of how US media institutions, policy think tanks, and academia have responded to rising polarization. Here is a lengthy extract:

Our new book, Asymmetric Politics: Ideological Republicans and Group Interest Democrats, tells the strikingly parallel stories of how the conservative movement simultaneously undermined popular faith in both mainstream academe and journalism among its supporters, building and reinforcing Republican reliance on alternative ideological information sources. Our investigation combines historical studies with analysis of partisan political messages, public opinion, media coverage and research reports stretching over several decades.

Today, we find that Republicans are more likely than Democrats to consume media that are openly aligned with their political orientation and to distrust other news outlets. The establishment of an explicitly right-of-center media ecosystem as a conscious alternative to “mainstream” journalism allows conservative media personalities to exert an influence over Republican officeholders and voters that has no true counterpart among Democrats. Similarly, Republicans have attacked university-based researchers for advancing leftist ideas and have built explicitly conservative think tanks to reorient Washington policy debates. We find differences in the content and sources of these elite information sources, which reinforce appeals to ideology among Republicans and specialized policy analysis among Democrats.

This structural imbalance both reflects and reinforces the larger asymmetry between the parties: Republicans are organized around broad symbolic principles, whereas Democrats are a coalition of social groups with particular policy concerns. Republican perceptions of widespread bias in the mainstream media and academic community encourage party members to view themselves as engaged in an ideological battle with a hostile liberal “establishment,” turning even their choice of news or research source into a conscious act of conservative self-assertion. Consumers of conservative news media and think-tank reports are exposed to a steady flow of content that further promotes that perspective.

Democrats, in contrast, are relatively content to rely on traditional news media and intellectual sources that often implicitly flatter the Democratic worldview but do not portray themselves or their consumers as engaged in an ideological conflict. Fox News Channel and conservative talk radio lack equally popular and influential counterparts on the left. Similarly, left-of-center think tanks have adapted to conservative upstarts by frequently opposing them in policy debates, but still retain broader ties to scholarly researchers and closer adherence to academic norms.

Both Democratic voters and elites therefore remain relatively unexposed to messages that describe political conflict as reflecting the clash of two incompatible value systems. Instead, the information environment in which they reside claims to prize objectivity, empiricism and policy expertise — thus remaining highly congruent with the character of the Democratic Party as a coalition of voters who demand targeted government actions. [my emphasis]

As an institutional account of how polarization has remade the “information environment,” this sounds like exactly the kind of story that can explain the “fake news” phenomenon. Indeed, the authors of a recent study of news media produced during the election cycle argue that the success of the right’s alternative media ecosystem comes, paradoxically, from a combination of its insularity as well as its legitimacy among conservative audiences. The latter is what forces mainstream news sources to respond to it, thereby giving it even more legitimacy.

Why isn’t this explanation deployed more often, even though, it seems to me that it is more likely to suggest what needs to be done (insofar as any explanation has the ability to do so)? (I will desist from positing “motivated reasoning” as an explanation here because that would defeat my point.) First, the level of explanation is institutional, unlike social psychology-motivated explanations that pitch their explanation at the level of a (socially shaped) individual and her response to particular media stimuli. It might be that institutional explanations simply don’t satisfy us because we like our explanations to be about what’s happening inside people’s heads. Second, because the explanation is institutional, its implications are also institutional. It suggests that the problem of information asymmetry will not improve unless trust in media institutions is restored; and this trust will only be restored within a new model of what counts as an “objective” news media institution.

It is here that STS might conceivably help us think of other models of objectivity in our efforts to create trust-worthy media institutions (i.e. trusted by both liberals and conservatives) in an age of polarization, information asymmetry, and curatorial platforms. Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison have shown, through their study of natural history atlases, that even in science, objectivity has shifted from an emphasis on “truth-to-nature” to mechanical reproducibility to “expert judgement,” through the 19th century. In her comparison of the American, British and German regulation of biotechnology, Sheila Jasanoff characterizes each national regulatory style as “contentious,” “communitarian,” and “consensus-seeking” respectively. In the German polity, for example, she finds an emphasis on the representativeness of knowledge-making bodies, while the United States hopes to resolve regulatory issues by having the different parties face off in an adversarial manner by having experts debate the “facts.” If a robust, deliberative, and “objective” public sphere is essential to the health of a democracy, there is no reason to think that “facts” and “truth” (construed in a particularly scientistic way) are the only basis of objectivity. The million-dollar question, of course, is to think of an alternative—as well as create robust institutions that embody it.

[Parts of this post are drawn from a piece I wrote for the American Sociological Association’s Science, Knowledge, and Technology section.]

Footnotes:

[1] Despite the oddity of the term “fake news,” and its even odder co-optation by President Trump, I will continue to use it in this post as the marker of a specific set of concerns around the production and dissemination of information and knowledge.

References:

Daston, Lorraine, and Peter Galison. 2010. Objectivity. Zone Books.

Grossmann, Matt, and David A. Hopkins. 2016. Asymmetric Politics: Ideological Republicans and Group Interest Democrats. Oxford University Press.

Jasanoff, Sheila. 2007. Designs on Nature: Science and Democracy in Europe and the United States. Princeton University Press.

1 Comment

Very much enjoyed this.

1 Trackback