When we think of servers, like web servers and Amazon servers, we don’t usually think of them as occupying physical space. We might think of a remote data center, thanks in large part to images that have been circulated by companies like Facebook and Google. But still, these only visualize unmarked buildings and warehouse rooms, showcasing a particular tech aesthetic of colored wires and tubes, and neatly assembled rows of blinking machines (Holt and Vondereau 2015). Such imagery is hardly meant to provide the public with a sense of where servers are actually located. For most day-to-day computer users, it often doesn’t matter at all whether servers are in the U.S. or China or Russia, so long as they work.

Inside a data center. CC BY-SA 2.0.

But server location matters, and many groups of people value certain material benefits and effects of the placement of servers and their own proximity to servers. It matters for online gamers, who want to play as close to servers as possible to get the fastest connection (known as “ping”) and to reduce lag. It matters in a similar fashion for Wall Street traders, who sometimes strategically locate themselves closer to servers to gain a speed advantage in stock trading. Because racks of servers generate loads of heat, server location matters for cloud computing service corporations; they tend to situate their data centers in colder climates to make use of financially-sound “free cooling,” a process by which cold air is circulated from outside in place of an electric cooling system. As a result, server location also comes to matter for environmentalists, since free cooling is a more environmentally sustainable option for these unbelievably inefficient structures.

The effects of physical location on hardware and personal performance demonstrate a kind of relational liveliness to servers. As networking machines, servers embody relations, facilitating the flows of materials and shaping senses of time and space. In this way, servers represent more than just rows of blinking machines. For instance, the location of servers in geopolitical space raises a number of questions regarding the politics of digital data online, such as the debates around national data sovereignty, and the rapidly changing forms of information infrastructures. In this post, I explore what happens when a popular social media platform moves their servers from one geopolitical space to another.

LiveJournal and Russian Politics

In December 2016, the blogging site LiveJournal, still an actively used social media platform predating Facebook, and at the time already owned by a Russian company as of 2007, announced that its servers were being moved from California to Russia. Accompanying these servers on their digital journey were millions of pages of user-generated works of fiction, fan-fiction, and personal musings. The move initially caused a number of users to migrate their accounts and texts to other platforms out of concern for their security and in protest of the Russian government. However, in April 2017, LiveJournal released a new Terms of Service agreement, in which it aligned itself with Russian law, most notably banning “political solicitation” and requiring content warnings on works considered “inappropriate for children according to Russian law.” For users, this shift raised numerous concerns over privacy, security, and censorship, especially regarding Russia’s strict prohibition on LGBTQ content and Vladimir Putin’s upcoming campaign for re-election in 2018.

The reconfiguration of LiveJournal as not only owned by a Russian company but also located in Russia signaled a geopolitical shift, and from this arose abundant legal, social, and political questions. When the Russian company SUP Media purchased LiveJournal ten years ago, nothing seemed to have changed—at least for users in the U.S. The servers remained on U.S. soil, divided between Montana and California, and no significant changes were made to the Terms of Service, though there was some chatter among users over whether they could trust this new company with their content. However, things were different in Russia, where LiveJournal has been one of the most popular blogging platforms, especially for discourse and journalism in opposition to the Russia state. Some argued that because SUP Media has had direct ties to Russian state security, this new ownership signaled a political alignment of LiveJournal and the Kremlin. In recent years, the site has been plagued by direct denial of service attacks—attempts to overwhelm servers to make a website inaccessible—likely to stymy political dissent at Russian election times.

It was only when the servers moved to Russia at the end of last year that the mass exodus from LiveJournal began in earnest. The geographical change had a number of consequences. Many LiveJournal users and legal experts used online platforms to weigh in on whether Russia has had any legal jurisdiction over U.S. citizens and their data, before and after the move. Some maintained that there was a security threat even before the servers moved because of SUP Media’s political connections. However, with the servers in the U.S., any attempts by the Russian government to directly control activity on LiveJournal would have likely been met with suspicion, derision, or an injunction. Relocating the servers made room for the alignment of the site, the servers, and the state. With the servers firmly situated in Russia, users’ activities on LiveJournal are occurring in Russia. It stands to reason, then, that ownership of servers as corporate property is only one piece of the puzzle.

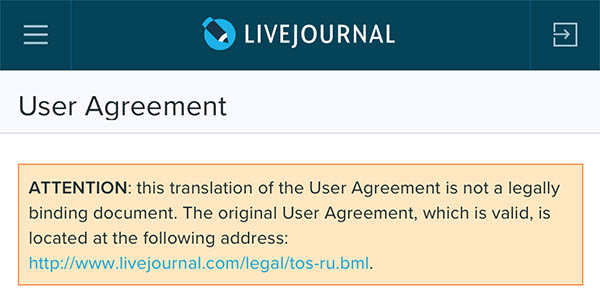

The situation was exacerbated by the technocratic register of legal language, preventing users from understanding their data rights under a new geopolitical legal regime. When SUP Media released new Terms of Service for LiveJournal in both Russian and English, the English translation was accompanied by a disclaimers that read: “this translation of the User Agreement is not a legally binding document.” A contingency of English-speaking users clamored to translate and interpret the legally-binding Russian text, drawing out some of the finer points of the content restrictions mentioned above and leading to many users beginning their virtual migration to other LiveJournal-like platforms. Luckily, LiveJournal’s servers are open-source and creating a mirror site is legally permitted.

LiveJournal’s User Agreement Disclaimer. Screenshot by author.

Anything But Neutral

This case of LiveJournal’s official servers moving to Russia shows us that the materiality and location of the physical infrastructure behind social media is much more important than we typically think. Social media is—even down to the level of servers—deeply entangled in an intensely located politics. Servers are located all around the world; Facebook has data centers in the U.S. and Sweden, and is expanding to other nations. Yet the servers themselves take on an assumed neutrality, since we aren’t typically privy to the location of servers and how they follow normative rules according to their locality. This fallacy is made all the more urgent given Russia’s involvement in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. If the recent revelation of Russian-sponsored ads on Facebook and falsified Russian Twitter users is any evidence, social media is anything but neutral.

Also at stake are ongoing international debates regarding the geopolitics of cloud computing, and the tactics that governments and corporations use to safeguard their data sovereignty (Amoore 2016). Following an appeal in the court case Microsoft Corp v. United States, wherein the U.S. is seeking to gain access to data on a U.S. citizen that is stored on servers in Ireland, the Supreme Court will soon oversee a trial that might determine whether the U.S. government can have access to data located on servers in other countries. The result of this case could have devastating consequences for data privacy, confidentiality, and security. In my own dissertation project on the relational liveliness between online gamers and gaming servers, I look into the legal dimensions of server location, asking how private servers and other servers often become complicated by their locatedness outside the U.S. How will legal regimes come to take servers and their geopolitics into consideration, and what sorts of power relations, inequalities, and rights will new legal frameworks generate?

References

Amoore, Louise. 2016. “Cloud geographies: Computing, data, sovereignty.” Progress in Human Geography:1-21.

Holt, Jennifer, and Patrick Vonderau. 2015. “‘Where the Internet Lives’: Data Centers as Cloud Infrastructure.” Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures:71-93.

I learned about this story and drew most of the details of the case summary from Advox, io9, and The Washington Post.

3 Trackbacks