When you’re playing an online game and it gets shut down, typically a message flashes on the screen that says something like: “You have been disconnected from the server.” This very message indicates that it is not just “the game” per se that you’ve been disconnected from. What is “the game” after all? In reality, players are connected to a shared version of a virtual world thanks to the workings of servers, those digital devices that make up the backbone of the internet and of virtual worlds, like Second Life and World of Warcraft. When a virtual world dies, when it’s “turned off,” the player is no longer accessing the same server as their friends. In fact, they’re not accessing any server at all. When the server is turned off, the game world is popularly said to have been abandoned—its software becomes referred to as “abandonware.” And just like that, a whole world dies. This post reflects the work of one group of video game enthusiasts and how they are actively working to bring so-called “abandoned” online games back to life by reshaping copyright laws and redefining games as cultural heritage.

Who Controls Abandoned Worlds?

A game developer might cease to support a game world because not enough players have remained interested and continued to buy in, making the game not profitable to run. Operating servers, the backbone support of all game worlds, is expensive after all. While the word “abandon” can mean to cease to support or to leave a place empty or uninhabited (from the Oxford English Dictionary), abandonment has another meaning etymologically. The word “abandon” comes from the Old French abandoner, from the Latin words, “ad” (meaning ‘to’ or ‘at’) and “bandon” (meaning control). Literally, abandon once meant “to bring under control” or “to surrender to someone or something.” In other words, abandon might also have this meaning of “to relinquish control and to put something under someone else’s control.”

In this sense, to abandon something is to signal not just a desertion of a place, but a change of hands, or a transferal of control over a property. It might stand to reason, then, that the word “abandon” was chosen strategically for “abandonware,” to signal such a transferal of control from software developer to users, a surrender of orphaned software to someone else. In the case of online games, this would make some sense, right? The company is no longer making money from the game. The game goes offline. The players, who have put time, effort, and money into building up communities, personal reputations, and character profiles, take over to keep it online. When these worlds are disconnected, many players do feel a sense of ownership or entitlement over these titles after they’ve been turned off. But these worlds are not just worlds—they are also intellectual property. Even though they are no longer commercially available, they are still copyright protected works, owned by corporations. Thanks to this legal stipulation—this more legal definition of “abandonment”—to abandon is not to transfer control or ownership, especially in the case of online games. Celia Pearce (2009) has written extensively regarding virtual world diaspora and how communities leave abandoned game worlds and reconstitute themselves and continue to thrive past a world’s expiration date. This might also be seen as a form of abandonment though, abandoning hope for the possibility of their home world’s return. It is in this space of possibility, one rife with hope, nostalgia, and resilience, where the laws around online game preservation and restoration might be modified to shift control, as the very term “abandonware” might suggest.

Cultural Heritage as Fair Use

The Museum of Art and Digital Entertainment. Photo by author (Oakland, CA, April 2018).

The current fight for the preservation of online games and virtual worlds in particular is largely being fought by a museum in Oakland, CA, called the Museum of Art and Digital Entertainment, or the MADE. The mission of the MADE is simple: to make video game history playable and to inspire the future generation of game developers. The MADE has successfully lobbied the US Copyright Office to classify this type of in-museum gameplay as “non-infringing fair use,” which allowed them to make their collection of 6,000 video games, from many time periods, available to the public to play for a $10 admission fee.

The museum is tapping into the adaptability of gamers and the law, but the fight hasn’t been easy. In the three years The MADE has been trying to actively change copyright laws; they have become active participants in the legal discourse around abandonware, as they have worked to make these titles available to the general public. The museum has successfully restored players’ access to a game called Habitat, the first ever graphical online virtual world. This project, a rare success story, had the full support of every entity who owned a piece of that virtual world, including the original developers, the owners of the source code for the game and the server, and the developers of the original server that it ran on.

This kind of active participation in the preservation of video games as is an extension of media scholar Henry Jenkins’ notion of participatory culture (2006). Jenkins analyzed how participatory culture audiences change the way media is consumed and perceived, affecting development and production decisions. The work of the MADE expands this notion of a participatory audience of fans who appropriate and transform media; there is now this new development wherein participatory audiences are actively engaging in altering the legal foundation upon which their participation in this media culture relies—the spaces of abandoned online games that must be hosted on servers. Their success in these transformative practices have depended upon the redefinition of video games as a form of a cultural heritage. Calling video games “digital heritage” or “cultural heritage” signals a similar discursive shift as the use of the world “abandoned” to describe “abandonware.” Heritage implies a passing down of property through the generations. According to the MADE, as a result of the participation of fans and players in the culture of video games, we have inherited the rights to video games as a medium.

The director of the museum told me that “the video game industry does little to preserve its own history,” and instead has had a long history of abandoning tangible artifacts of video game history and game development. At one point, a load of source code for previously unreleased Atari 7800 games was found on floppy disks in a dumpster behind their corporate offices in Sunnyvale, CA when they closed in 1996. A concerned person broke the law by trespassing on Atari grounds and taking the disks from the dumpster and preserving them online. The Director noted that, “the industry’s history is littered with stories like this.” This is what video game preservation often looks like and is a reason the MADE insists that video games are cultural heritage. If game companies won’t care for these works of art, then museums, archives, libraries, and the general public have inherited the responsibility. Until recently, online game servers have not been considered cultural heritage, but that could be changing.

Preservation at the Source

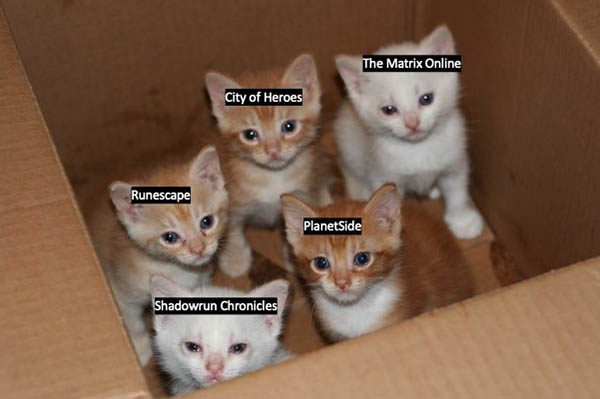

Abandoned games depicted as abandoned kittens. Photo from Wikimedia Commons, with author edits.

This year, the Copyright Office made a decision regarding the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, in effect giving institutions like the MADE and archival organizations the right to break digital rights management protections of server source code IF that source code is obtained legally. This gives the server unique value as a proprietary object, especially since the transferrable ownership of the abandoned server is now the only thing standing in the way of online game preservation. Since the decision was announced, the MADE has seen an increase in requests to save games that are dying now, and to restore games that have already been disconnected. But obtaining server source code will not be so easy, as it is still intellectual property, tightly controlled by developers or their parent corporate entities.

The primary limitation of this decision, though, is that the game must be played locally on the premises of the museum, limiting the audience of these preserved titles to those who can reach Oakland, CA. These preserved worlds, rather than being offline and archived somewhere out of reach by the public, would be available to play on site, though the world would be empty, devoid of social interaction, or minimally populated over a local area network that does not extend beyond the boundaries of the museum. Sort of like abandoned (“empty and uninhabited”) worlds still, right?

Video game fans, driven by nostalgia and a desire to claim some semblance of ownership over these abandoned video games that are experienced as worlds and homes by thousands of people are making strides toward preserving them by asserting that online games and the servers that run them should both treated as cultural heritage. As this passionate work has shown, there is potential for fandom to be the starting point for changing conservative copyright laws in this country. But really, they have a long way to go before copyright law is expanded to preserve with abandon what we might call our technological-cultural heritage.

References

Jenkins, Henry. 2006. Fans, bloggers, and gamers: Exploring participatory culture: NYU Press.

Pearce, Celia, and Artemesia. 2009. Communities of play: Emergent cultures in online games and virtual worlds. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

For more on video games as cultural heritage, see:

Barbier, Benjamin. 2014. “Video games and heritage: Amateur preservation?” Hybrid. Revue des arts et médiations humaines (01).

Khong, Dennis WK. 2006. “Orphan Works, Abandonware and the Missing Market for Copyrighted Goods.” International Journal of Law and Information Technology 15 (1):54-89.

Maier, Henrike. 2015. “Games as Cultural Heritage: Copyright Challenges for Preserving (Orphan) Video Games in the EU.” J. Intell. Prop. Info. Tech. & Elec. Com. L. 6:120.

2 Comments

Hi Evan Conaway,

A game developer might cease to support a game world because not enough players have remained interested and continued to buy in, making the game not profitable.

Good day! Thank you for sharing!