“One thing is certain: When something is scientifically complex, it’s harder to understand and to communicate” (sciencebranding.com). Regardless of its accuracy, this is a commonly repeated sentiment across many public domains. However, this particular claim was produced within the branch of marketing known as Science Communications with the peculiar intent of convincing drug companies they need to hire “creatives” to extol the virtues of biochemistry to physicians. This is just one manifestation of the Science Communications field, which includes academic journals, NGOs, and PR firms. Armed with the more edgy truncation “SciCom” (or SciComm), the field increasingly resembles other promotional paradigms such as experience design (UX) and immersion marketing, wherein the goal is to seamlessly weave advertising into the condition of being alive.

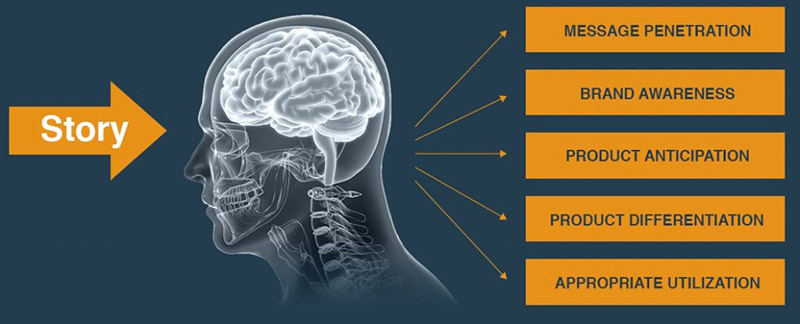

Promotional image from sciencebranding.com

There are two general strands of SciCom that, while ostensibly beholden to different interests and aims, coil around the same ends and means. Less subtly, there are high-end PR firms whose clients include biopharma and biotech companies, for whom they translate the latest breakthroughs in the commercialization of health to potential investors. Spectrum, for instance, is a “full-service strategic health and science communications agency that believes in the power of scientific storytelling to clarify complexity, capture imaginations, shift mindsets and move markets.” The other side of SciCom consists of government-funded and philanthropic outfits that are committed to increasing scientific literacy among the public. This latter wing of SciCom is the concern herein, because while it’s easy to juxtapose the nefarious marketing-pharmaceutical-complex against noble efforts of non-profit advocates for the democratizing power of education, the plotlines aren’t quite so readymade.

Angular Vaccinations

I had the fortune of participating with a team of non-profit science communicators staging an exhibition at an “arts festival” (a low-profile Burning Man in the Oregon high desert). Our presence at this festival was financed, in part, through the NSF’s Advancing Informal STEM Learning (AISL) program as part of a larger $938,029 grant. The grant application states that the aim of my temporary colleagues was to investigate how “people with low to no affinity for science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) can be introduced to STEM ideas in ways that are appropriate for their cultural identity and…allow for continued STEM engagement.” The NSF’s AISL program is part of a nationwide initiative to prioritize STEM education, which, along with millions of dollars per year from the Department of Defense (Lim et al. 2013), constitutes significant investment in promoting scientific thinking among the U.S. population. Perhaps this is an admirable goal in a time of highly-politicized disagreements over the validity of climate science and vaccinations. However, in considering the populations that are targeted for this STEM marketing, peculiar motivations appear to surface.

Interestingly, the NSF’s role in STEM promotion at the festival in which I participated was concealed behind the brightly-colored and angular fonts of a London & New York-based SciCom syndicate. That is, the NSF outsourced the job of persuading public thinking about science to professional thought-benders. For good reason. Had festival-goers been aware that our exhibition was specifically designed to dissuade them from the astrology, neo-spirituality, and the other bits of esoterica being practiced elsewhere at the festival, they would have been rightly skeptical of our “product.” Such attempts at STEM propaganda by the NSF eerily echo the CIA’s efforts during the Cold War to promote the idea that the U.S. values freedom of expression (see the funding of abstract expressionist exhibits in Eastern Europe, Wilford 2008) and recent efforts at “hip-hop” diplomacy in Islamic-majority countries (Aidi 2011).

Newtonian Psychotropics

The NSF grant of which I was a partial beneficiary proposed to target “cultural events that attract audiences who do not identify themselves as interested in science or broader concepts associated with STEM.” However, such claims are directly contradicted by the increasing convergence of arts festivals with the tech industry (Turner 2009). Beyond this Palo Alto-Burning Man synergy, in casually conversing with festival attendees no one denied anthropogenic climate degradation. Indeed, many expressed pointed concern about the effect of atmospheric CO2 on the planet’s temperature. Does this not signal a level of scientific appreciation greater than many other subcultures in the U.S.? Granted, there were espousals of UFO theories, the causal influence of Jupiter’s moons on geopolitics, and discussions of deeper consciousness abetted by psychotropic chemicals. While adherents of such beliefs might be considered “wrong” by the STEM police, these subjects actually speak to a vivid scientific interest (if not knowledge)—UFOs are nothing if not a fetishization of technoscience, tracking the orbits of Jupiter’s moons requires an acknowledgement of at least Newtonian mechanics, and LSD is a very powerful experiment in neurochemistry. If indeed the goal is to introduce STEM ideas to people with low to no affinity for science, the NSF may be targeting the wrong audience.

Rather than a disinterest in scientific knowledge, the audience of this particular festival seemed to display a thirst for answers outside the dominant regimes of knowledge production used to reproduce a society which leaves them empty, alienated, and unequal. Large pavilions at the festival were dedicated to lectures on topics such as: “spiritual practice and collective responsibility in a post-Trump world,” “body-wisdom and energetics,” “activating inner goodness and creating body-peace through spiritual self-care,” “sacred geometry,” and “dream hacking.” More concisely, one lecture declared that “we live in a dramatic age with high stakes for the planetary future. To help us navigate this threshold of transformation, we need every available source of relevant insight.”

These interests don’t foremost announce an anti-science bent so much as an anti-status-quo bent. There is more concern with rearranging the social order than the epistemological order. If the NSF’s AISL program were genuinely about cultivating public science literacy, one wonders why there are not comparable efforts by the NSF to penetrate Christian fundamentalist groups or sponsor climate change PSAs. Why does the NSF choose to spend promotional money on convincing ravers that science is cool, as opposed to convincing creationists that the planet is 4.5 billion years old? I would suggest the answer lies less in these communities’ relationship to science than their relationship to power—evangelical Christianity actively promotes adherence to the status-quo power relations that have organized colonizing populations over the last five centuries (Grice-Hutchinson 2009; Tanner 2005, 2019).

Philanthropic Biopower

Do the NSF’s efforts at STEM promotion aim to make U.S. citizens smarter? Maybe. Though training and hiring more teachers seems a more salient route to this goal than sending open-minded anthropologists to off-brand Burning Men. Does publicly-funded STEM promotion aim to make U.S. citizens more profitable and predictable? Probably. The largest sectors of the global economy (finance, tech, medicine, insurance, resource extraction) are all premised on faithful adherence to the predictive reality of science among consumers, as well as continued breakthroughs in math and material science. The colonizing economy was built out of STEM innovations.

Aside from the occasional NSF grant and other commissioned events, the SciCom outfit that facilitated my festival experience is funded by the Wellcome Trust, the wealthiest charitable organization in the U.K. At £25 billion their endowment is second only to the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation worldwide. The charity profits about £2.9 billion per year on its investments and disperses about £1 billion per year on grants and philanthropy. The Wellcome organization’s riches originally derived from the pharmaceutical industry, and much of their philanthropy is dedicated toward research in those same biopharma and biotech sectors that employ SciCom firms to promote the profitability of their biopower.

While at first glance it seems like public or charitably funded efforts at SciCom are promoting a rigorous framework for thinking and producing knowledge, the circuitous ability of the Wellcome Trust to profit from its philanthropy and the hashtaggable experiences designed by SciCom firms bespeak a far less noble pursuit. Rather than encouraging the educational skills that would empower the public to responsibly interpret rhetorical deceptions like those deployed in campaigns to defraud climate science, “non-profit” STEM promotional efforts seem much more like marketing efforts to brand science as a fashionable style of thinking—science reduced to an identity-marker like the familiar marketing adjectives organic and sustainable. Science Communicators are trying to persuade the public to switch from organic to scientific knowledge. Marketing is a practice that avowedly dissembles and obfuscates. Perhaps, then, this is not the best rhetorical tool for education, particularly as it concerns the purported truth-value of scientific knowledge production.

References:

Aidi, Hishaam. 2011. “The grand (hip-hop) chessboard: Race, rap and raison d’état.” Middle East Report (260):25-39.

Grice-Hutchinson, Marjorie. 2009. The School of Salamanca: Readings in Spanish Monetary Theory, 1544-1605. Auburn: Ludwig von Mises Institute.

Lim, Nelson, Abigail Haddad, Dwayne M. Butler, and Kate Giglio. 2013. First Steps Toward Improving DoD STEM Workforce Diversity. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Tanner, Kathryn. 2005. Economy of Grace. Minneapolis: Fortress Press.

Tanner, Kathryn. 2019. Christianity and the New Spirit of Capitalism. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Turner, Fred. 2009. “Burning Man at Google: a cultural infrastructure for new media production.” New Media & Society 11(1–2):73–94.

Wilford, Hugh. 2009. The Mighty Wurlitzer: How the CIA played America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.