Kashif pointed to different parts of the wounds on his leg and explained to me how they had healed, exacerbated, or been ignored at different places of care. He had gotten a chemical burn injury on his left leg a year ago while mixing HCl (Hydrochloric acid) and H2O2 (Hydrogen peroxide in bleach), two highly reactive chemicals, almost on the spot of the textile factory where he stood now and talked to me. He was not among the first few people introduced to me by the Safety and Security Officer because he was not considered disabled among the workers at the factory I was conducting fieldwork in Punjab, Pakistan.

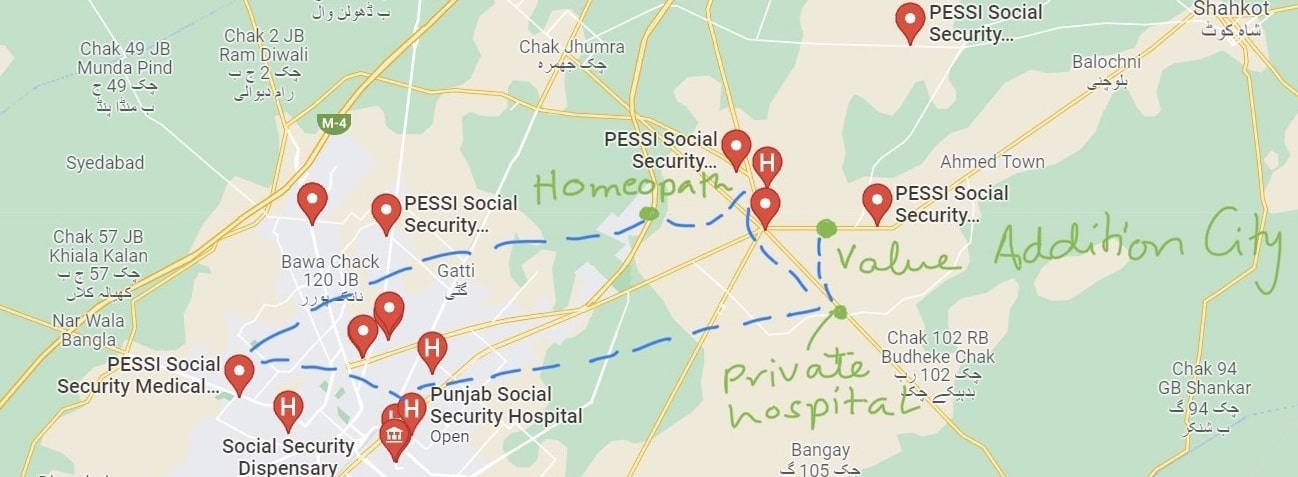

Similarly, the welfare system did not consider his burns a temporary disability because burns do not limit mobility and do not impact workability. The private healthcare facility assessed, provided him with medicine, and advised him to stop working at the textile machine where hot water takes the scab off his wounds, and the wounds don’t have the chance to heal. He ended up at Social Security to ask for an extension for injury-related leaves, but his injury did not qualify as a temporary or permanent disability because it did not stop him from going to work for more than two weeks. He had gotten as many leaves for an injury as possible. Now he was waiting to go to the homeopath, recommended for chemical burns by his co-workers, and a private dermatologist. Kashif inhabits the space between injury and disability, especially one where he keeps going back and forth between several nodes of care. Together, these make the landscape of care in relation to the Special Economic Zone called Value Addition City in Pakistan (Fig 1.1).

A map of Value Addition City and neighboring places of care like the Social Security Hospital and private institutions of care.

Movement of a worker through the landscape of care in and around the Special Economic Zone called Value Addition City in Pakistan.

Workers go between these nodes of healthcare to receive care where possible but also to navigate the narratives of responsibility stemming from different vantage points of caregiving while maintaining both bodily and social fitness for work. Care, responsibility for injury, and fitness play out in conjunction with one another in Pakistan’s textile industries where workers are regularly injured and often are permanently disabled. Injuries, like Kashif’s, often heal to a degree that allows workers to keep working; these injuries are dismissed as “part of the job.” This can be seen in the decline in officially recorded disability rates from the census in 1998 to the one in 2018 (Pakistan Bureau of Statistics 2022). On the other hand, research shows that work-related accidents in the country have increased drastically from 2002 to 2018 (ILOSTAT 2018). The discrepancy between recorded accidents and disability rates highlights how the categories of disability and labor health intersect such that workers are caught between injury and disability. I try to understand this by asking: how has fitness, measured before employment and after an injury, been constructed for workers to aid this? What role does biomedicine and narratives of responsibility play in defining worker fitness in case of a workplace injury?

Biomedicine at Work

When a worker gets injured, they receive immediate care from either the factory’s emergency facilities or the Social Security emergency services. The injury is reported to the management who reports to Social Security. The Employees Social Security Institution, since its establishment in 1967, collects welfare contributions directly from industrial employers and distributes them to injured or disabled workers with the state acting as a mediator. As a mediator, Social Security investigates the likelihood of the narrated incident that caused the injury. These investigations are based on biomedical evidence from the injured person’s body and whether the injury is likely in their work setting and according to co-workers’ narrative of the incident. These investigations are, then, corresponded with laws like the Worker’s Compensation Act 1923 which decides what percentage of bodily loss qualifies for temporary or permanent disability benefits. Biomedicine and entangled legal discourses and practices determine which embodiments will receive benefits or not and which are allowed to work or not.

Over the years, the welfare system has aligned itself with private industry in how disability is assessed through workers’ ability to perform the particular tasks assigned to them in the industry. These assessments are made through medical fitness tests tailored to the worker’s role in the factory and notes from work managers needed to qualify for disability benefits. Doctor Zahid explained how biomedicine is operating in this realm to make fitness equivalent to the body’s workability within the industry. He explained this through the similarities and differences between a soft tissue injury and a fracture. While the care for both is similar such that minimal to no movement is advised, bones and tissues are given very different places in how they affect fitness for work. Biomedically, a fracture is seen as a more intense break in the body than a soft tissue injury hence it classifies for more time off work through the Social Security system. A soft tissue injury, on the other hand, is considered to not impact workability hence a worker is responsible for its healing while working regularly. The biomedically hierarchized importance of different parts of the body determines how responsibility for healing is parsed out in everyday work settings and how and when a worker becomes fit post-injury.

Responsibility for injury and healing are woven into what it means to be a fit worker. While Kashif needed to navigate blame for injury while receiving care to be fit and to keep working, Doctor Zahid showed that biomedicine and workability determine responsibility for healing and when a worker is considered fit. Fitness, in both cases, is a socio-physical phenomenon constructed through movement in the landscapes of care as well as in everyday work settings. While the movement through the various places of care can be seen as navigating bureaucratic red tape (Hull 2012; Gupta 2012; Mathur 2017), it also shows how responsibility is experienced by workers and has to be navigated through moral claims around blame for injury and time taken for healing stemming from different places of care. Fitness that is ascribed as a result of movements across several spaces of care is as much a moral phenomenon as a physical one. A focus on movement visualizes how care is sought in and around the Special Economic Zone, which can be a way towards strengthening networks of care present rather than a sole focus on the possibilities of work as mediated through systems of welfare.

References

Gupta, Akhil. Red Tape: Bureaucracy, Structural Violence, and Poverty in India. Duke University Press, 2012.

Hull, Matthew S. Government of Paper: The Materiality of Bureaucracy in Urban Pakistan, 2012.

ILO. “ILOSTAT.” ILOSTAT Non-fatal Occupational Injuries, August 14, 2018.

Mathur, Nayanika. “Bureaucracy.” Cambridge Encyclopedia of Anthropology, November 9, 2017. https://www.anthroencyclopedia.com/entry/bureaucracy.

Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. “Disability Statistics.” Pakistan Bureau of Statistics Government of Pakistan, August 14, 2022. https://www.pbs.gov.pk/content/disability-statistics.