In the sweltering early hours of summer 2022, waste pickers make their way towards Mumbai’s Deonar dumping ground. Devi, a young waste picker, holds up a thin plastic bag, saying, “These are everywhere, but they’re so flimsy!” Vikas, a more senior segregator, sifting through a pile nearby, replies with a grin, “Ah, but that PET bottle in your other hand? Now that’s valuable. You’ve got to know your plastics, Devi.” Their daily interactions with these materials have given them an innate understanding of their worth and properties.

It is here, amidst a sea of discarded materials, that a relationship evolves—one between the waste pickers, the myriad forms of plastics, and the urban space that surrounds them. This bond is grounded in empirical observations that bring order to the chaotic array of plastics, tying together the intricate dance of humans and materials within the city’s polyphonic rhythms. They carefully separate Polyethylene Terephthalate (often used in clear water bottles) from High-Density Polyethylene (commonly found in milk jugs and detergent bottles) with practiced precision. This meticulous sorting is not just about plastic types. It also hints at a broader economic story. Each plastic has its own market value, with clear bottles fetching different prices than sturdy containers. This value-driven distinction showcases an intricate dance of supply and demand, where understanding the nuanced language of materiality translates directly into earnings for the waste pickers.

Plastic accumulation in a storm water drain, with children playing amidst the debris in Deonar, Mumbai. Photo by Sidharth Chitaliya.

In Mumbai, plastics transcend their physicality. Here, they become containers of stories, agents of exchange, and symbols of a society grappling with the dichotomies of modernity. As we delve deeper, the complex relationship between the human and non-human actors unveils itself. The plastic embodies more than a material presence; it holds narratives, memories, and even potent futures, intertwining seamlessly with the lives it touches. It becomes apparent that the plastic and the documents overseeing its trajectory share a symbiotic relationship, a dance of agencies, where each shapes and is shaped in return, weaving interconnected stories unfolding in the urban ecology of Mumbai.

Plastics and People

Located in Mumbai’s M-East Ward,[1] the Deonar dumping ground holds a pivotal role in the lifecycle and narratives of plastics in the city’s urban ecology. Established in 1927, it has grown to be one of Asia’s oldest and largest dumping grounds, spanning over 132 hectares (Chatterjee 2019). Waste pickers sift through the city’s refuse every day, maneuvering mountains of waste to reclaim plastics that hold potential for recycling (Roy 2021). Amidst this organized chaos, materials that were once a part of daily lives find a transient rest, only to be rebirthed through recycling processes facilitated by a network that spans the city. The Deonar ground highlights the city’s waste management challenges due to frequent fires and environmental issues. It’s also where bureaucratic documents intersect with waste, shaping the narratives of plastics in Mumbai’s urban landscape.

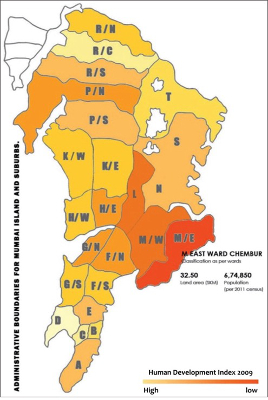

Administrative Wards for Mumbai Island and its suburbs. Image: Amita Bhide.

As an ethnographer from a North American university at the Deonar dumping ground, I was a stranger navigating this unfamiliar terrain, seeking to understand the relationship between people and plastics that shape Mumbai’s urban narrative. I find the waste pickers deep in conversation. Under a sky gradually shedding its darkness, they share moments of pause in an otherwise unceasing flow of work. “Bhai [Brother], see this one, its texture tells me it housed something precious once,” remarks a seasoned picker to his younger counterpart, holding a piece of Polyethylene Terephthalate with an almost reverential gaze. The younger one nods, his eyes lighting up as he responds, “Who knows what it will be made into now?” Their conversation paints the plastics in potentiality, seeing not just what it is but what it could be. There are others around them, engaged in similar dialogues. One holds up a bottle cap, remarking, “Didi [Big sister], remember the time when we found hundreds of these, and we sent it to Dhule?”

This specific journey to Dhule is not just a fleeting memory but signifies a broader pattern. Most of the Mumbai’s plastic waste is processed in towns surrounding the city. They are transformed into pellets in places like Dhule, only to be brought back to the metropolis. This cyclical movement stands as testament to the unexpected pathways that plastics tread in their lifecycle within the city and its outskirts. Making their way through the materials, the workers narrate and listen to the stories embossed on the very being of these plastics—stories of dinners and drink shared, of daily routines and special occasions. Each piece of matter forges an intricate network of shared experiences and intertwined destinies.

“It has seen Diwali festivities, Safiyya, I am sure of it,” a picker remarks, holding up a vibrant piece of plastic adorned with patterns reminiscent of traditional Diwali motifs. The patterns are more than mere decoration; they are echoes of Mumbai’s many histories. This contrast is especially poignant considering Safiyya, and many waste pickers like her, belong to the Muslim community—a community that faced severe trauma during the 1991-1992 Mumbai riots, which saw Hindus and Muslims pitted against each other. Now, years later, the interplay of a Muslim picker sifting through remnants of a predominantly Hindu celebration in the backdrop of a nation wrestling with Islamophobia underscores the city’s historical divides and enduring complexities.

Evening scene at Deonar Dumping Ground, Mumbai, with trucks and daily activities in the foreground. Photo by the author.

Data and Dissonance

Close to the Deonar Dumping Ground, at the municipal offices of the M-East Ward, the second act of the day’s drama unfolds. This is where the plastic’s journey is documented, guided, and often reshaped, not through the hands of waste pickers, but through the well-articulated pathways charted on paper and digital screens. Many trucks transporting waste from places like the Deonar ground are now GPS-enabled, which allows for real-time tracking of shipments. As these trucks ferry plastics to various processing centers or towns, their routes, stops, and timings are monitored via digital platforms. This integration of technology ensures that the plastic’s journey—right from collection to eventual recycling or disposal—is mapped on digital screens. It becomes a place where the life of plastics is entangled with the life of documents.

An assistant engineer in the municipality, Vijay, pores over a weather-beaten report detailing the city’s plastic waste metrics. The document meticulously records data such as the source neighborhoods of the waste, the types and weight of plastics collected, and the specific municipal garbage trucks responsible for the transport. These entries, while numerical and procedural at face value, unravel the life story of every plastic piece at the site. They reveal which truck transported it, from which part of the city it originated, and even projects its next destination, probably a recycling factory. Each line item offers a glimpse into the journey of plastics—where they have been, where they are now, and where they are headed next, all within an intricate waste management network.

Vijay’s colleague, Reshma, joins him, bringing fresh perspectives from the ground level, from the accounts she gathers during her interactions with the municipal supervisors. “The recycling bays aren’t functioning at full capacity,” she remarks, tapping a finger on the pie chart on the page. “The quantity of segregated plastics coming out are a full ten tons less.”

Vijay nods, his face dims as he tries to understand the mismatch between the expected results and reality. He breaks the silence, his voice echoing a deeper unrest, “These reports… they tell stories. Yet they sometimes mask the undercurrents of conflicting interests. There’s a tug of war between the economic desires of waste pickers and private industries, the political aspirations tied to urban waste management, and the on-ground reality of the actual waste generated and processed. It’s not just about numbers, but the various narratives spun around the city and its waste.”

The exchange between the officials weaves a rich tapestry of the city’s entangled relationships with plastics—a tapestry that is continuously rewritten as strategies evolve, and dynamics shift. The daily notes, the reports, and documents in the office are far more than bureaucratic tools. They are a canvas where the city’s struggles, hopes, and realities converge (Hull 2012). A canvas that, like the ever-present plastic, takes many shapes and tells many tales—an entity constantly negotiating between the aspirations of the city’s administrators and the grounded realities of its inhabitants, between policy dreams and tangible immaterialities.

“We are caught in this relentless cycle, often feeling like mere cogs in a machine driven by policies crafted in rooms much like this one. Sometimes it’s about not meeting the quotas, sometimes about not complying to the outside diktat. Just last month we received training on recycling from these experts from Sweden. Just imagine!” Reshma says out aloud, while continuing to flip through the pages of the document. The data before them, with papers marked up in margins and annotations scribbled alongside figures, bears imprints of constant negotiations and re-negotiations. These annotations lay bare the stark disparities between the lived realities of the waste pickers and the bureaucratic processes that aimed to steer the narrative “See here,” Vijay pointed, his finger landing on a section titled Solid Waste Management Rules 2016, Mumbai, “This was envisioned to streamline waste segregation and collection, aligning with the broader Swachh Bharat Abhiyan [Clean India Mission] to promote cleanliness and recycling. But the ground reality? It’s chaos, Reshma, a tangled web of these envisioned plans and the real dynamics at play on the streets.”

Recycling and Records

As we move into the recycling bays, we find the hidden corners where plastics shed their older selves and metamorphose into something new. A manager at a recycling facility pauses in his instructions to a worker to explain, “It is not just about giving plastics a new life; it is about managing a resource that is so entwined with our city’s lifestyle. It is a serious business,” he says, pointing to a stack of papers. At every stage of this journey, documents play a silent yet potent role. “The documents are not just sheets with information; they are our guides, helping us negotiate the intricate pathways that plastics carve out in the urban space,” notes a worker at the recycling facility, her desk a landscape of papers that chart the life journeys of different plastic materials. This living chronicle, expressed through type, location, and quantity, showcases the intertwined destinies of materials and the city, and suggests a contested space in continuous transition.

Young plastic segregators sorting through recyclables amidst urban debris in Deonar, Mumbai. Photo by the author.

Municipal papers, guided by the state’s intentions (Das 2004), chart the journey of plastics in the city. Officials use these documents to manage the city’s environment and the people’s relationships with waste (Hull 2012). These records don’t just tell a story; they play a role in shaping policy and guiding the city’s approach to plastics (Anand 2023). Essentially, the documents aren’t just passive descriptions; they influence decisions and actions. They help make sense of the complex flow of plastics, reflecting the city’s past, present, and potential future.

Conclusion

The confluence of material technologies and documentary practices reflects multiple agencies within Mumbai’s landscape. Plastics are not passive entities but dynamic actors in a rich narrative shaped by bureaucracies, human endeavors, and the unyielding agency of materials (Doherty 2019; Davis 2022). The investigation beckon us to witness this bricolage and urge us to explore the life stories of plastic as they shape the city and re-shape the city.

Note

[1] Wards in Mumbai: Mumbai is divided into 24 administrative zones called wards, labeled from A to T. Each ward represents a specific region, facilitating localized governance and management by the municipal corporation. M-East is one such ward, capturing a distinct segment of Mumbai’s vast urban landscape.

References

Anand, N. (2022). Toxicity 1: On Ambiguity and Sewage in Mumbai’s Urban Sea. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 46(4), 687-697.

Chatterjee, S. (2019). The labors of failure: Labor, toxicity, and belonging in Mumbai. International Labor and Working-Class History, 95, 49-75.

>Das, V. (2015). Corruption and the possibility of life. Contributions to Indian Sociology, 49(3), 322-343.

Davis, H. (2022). Plastic matter. Duke University Press.

Doherty, J. (2019). Filthy flourishing: para-sites, animal infrastructure, and the waste frontier in Kampala. Current Anthropology, 60(S20), S321-S332.

Hull, M. S. (2012). Government of paper: The materiality of bureaucracy in urban Pakistan. University of California Press.

Roy, S. (2021). Mountain Tales: Love and Loss in the Municipality of Castaway Belongings. Profile Books.