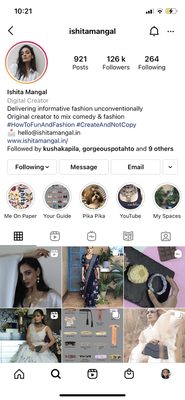

Screenshot of the Instagram profile of the influencer discussed in the blog.

Social media content creator Ishita Mangal (@ishitamangal) uploaded a post with multiple slides on her Instagram page. The first slide is entitled “an apology letter to my audience.” In the rest of the slides, she highlights a “barter collaboration” gone sour. The collaboration entailed the digital creator featuring four Indian kaftans (a type of clothing) brands on her Instagram page in exchange for keeping the outfits that she would feature. One of the brands was singled out, with their Instagram handle mentioned in the caption for viewers of the post to easily access. The brand was accused of harassing the digital creator; walking back on the terms of the agreement; asking for the garment in question back after “absorbing maximum benefits of all the posts on various platforms.” The digital creator proceeds to tell the tale of harassment and “extortion” she experienced at the hands of the luxury brand owner. The letter of apology–text contained in images spread across several posts–was meant for the audience of the creator to whom the “unethical” brand had been promoted.

Instagram screenshot of the apology post discussed in the blog.

Social media platforms, especially Instagram with its focus on photo and video sharing, have emerged as sites where pleasure, creativity, art, frivolity, entertainment, aesthetic representations, and capital become entangled. The above-mentioned instance fractures the seamless flows of sensory stimulation platformed by forces of global capitalism. The apology issued by the digital creator to her audience–her 125k followers who subscribe to her content–highlights the slippages between questions of valued forms of capital (aesthetic, social, cultural) and labor. The post by @ishitamangal lays bare more than just the precarity of economic relations on a platform that does not center labor (and labor rights) connected to the process of content production. The post also elucidates the peculiar sites (publicly accessible comments that gather engagement) through which precarities are made elastic; to cushion the blows that precarities make possible in the first place. In this particular case, the digital creator and influencer boldly titles her post an apology to highlight her own vulnerability while simultaneously showcasing the might of her own reach, the seemingly transient communities that thicken under her posts in the form of views, hearts signifying likes, supportive comments that mix texts with a whole host of expressive emojis. The particular apology post in question sits atop over 11,500 hearts and over 600 comments. The comments section is bustling with love and solidarity; from generic statements of support to statements of shared “bad” experiences with the owner of the brand in question and even other influencers chiming in with their horrid experiences with other brands.

Screenshot of an Instagram comment under Ishita’s post

The brand was outed by @ishitamangal for being “unethical.” The brand then put out its version of the events claiming that Ishita Mangal did not honor the terms of the agreement. This particular post gathered 423 likes and 50 comments, significantly lower than @ishitamangal’s post. Both @ishitamangal and @taniyakaurr are using their platform to highlight the unequal power dynamics that characterize the barter of goods and services as well as explicit monetary compensation. While the former mentions the “time and money” she invested in creating a post meant to promote the brand, Taniya reveals that she puts in a lot of “effort” in creating content. Having posed for multiple selfies and experimenting with lip-sync content on social media myself, I can attest to the investment of “effort” by the creator in question. Taniya’s comment brings forth what usually lurks under the surface: the question of labor. The “effort” that Taniya gestures towards encompasses more than just “time and money” that Mangal mentions. In my own experience, recording videos requires at the very least repeated attempts at producing the desired video/image worth posting. Fashion and beauty content creators like Ishita and Taniya make elaborate videos that involve several costume changes, voice performances, intricate make-up along with post-shoot edits which require laborious and sensorial engagement with tech devices. The labor of love is labor nonetheless.

It is both curious and interesting, however, that Ishita Mangal only brings up the question of “effort” (a more generic proxy of labor) until the second to last slide in her post. Even more curious is the context in which the question of “effort” is brought up. Having already established the fact that she had spent “time and money” into making the video which has reached “3 lakh” (three hundred thousand) users across various platforms, effort is the culmination of more than just her labor. The unalienable labor would not make sense in the market without her specific body, gestures, and the ambiance (her capital) that have made her content popular in the first place.

Her efforts then are not labor in the strict sense of the term as was first echoed by Marx (1958)–alienated from the body of the laborer, commodified, and sold without any reference to the person of the producer. Commodified labor is what allows the consumers to dissociate from the producers, the laboring bodies. While this may be true for the laboring bodies who made the kaftan that the brand sells, the labor provided by influencers like Mangal cannot be so easily alienated. Mangal brings up the value of her efforts in citing pricing discrepancies she experienced while working with the brand. While the brand told her that the garment she would showcase was worth Rs 26,000 (USD 348), she had heard from other customers that they had known the product had been quoted at Rs 22,000 (USD 295). The frustration over the worth of her “efforts” is entangled in conversations about the worth of her own body on the one hand and the tenuous worth of the brand on the other. It must be noted that her body is not hers alone, it is a class-ed, caste-situated, and gendered body. Her body does not just labor, it is capital that “invests time and money.”

Her efforts are not alienable labor. It is only in Taniya’s comment, whose follower count is a little over 1200, “efforts” take on a slightly different meaning. The “barter collaboration” that Mangal says she “felt” she should “use her reach to promote Indian labels.” As Taniya points out, however, for smaller creators, barter collaborations may not be a choice. Even in the response post that the brand shared, the barter collaboration is described as “mutually beneficial” and for allowing influencers to get access to items “which otherwise would not necessarily be available to them.” Again, the question here is not so much about compensation of labor but valuing bodies and worldviews, aspirations and possibilities for upward mobility (Dattatreyan 2020; Piliavsky 2020). While for Ishita the barter works as a favor to small, India-based brands, the brand views itself as providing worlds of consumption that might not be available to certain creators. Given the history of the content that Mangal puts out, even the insinuation of a lack of luxury that she cannot already afford would seem insulting. Mangal describes her content as “delivering informative fashion unconventionally” and herself as an “Original creator to mix comedy & fashion.” Her videos feature styling tips for western and traditional Indian outfits, with garments, jewelry, and accessories usually pulled out of her own closet. Her unconventionality comes from her deep knowledge of fashion and stylish clothing which allows her to confidently play around without jeopardizing her class status. Her videos and pictures are usually shot in luxurious backdrops, textured walls, elaborate floral arrangements, and stylized plant arrangements, small sculptures. Mangal produces her videos to the tune of a snarky script, sarcastic humor, and embracing her fashion-forward outlook which sometimes exists at odds with “traditional” beliefs of middle-class respectability. She is also a fashion designer and has a clothing brand called Quo.

In a post from November 13, 2020, Mangal presents tips on how to style a shawl. Set against an elaborate and richly detailed backdrop that could very well be the set for a professional photoshoot, she authoritatively suggests the accessories, jewelry, and garments that you need to effectively style the shawl. She makes a joke about being in front of a fan, as she stands with her long hair flowing, presumably standing in front of a fan. The joke is meant to poke fun at the popular film motif of the heroine with her naturally flowing hair. In the long list of suggestions, she then advises you to “take the most expensive shawl from your mom’s closet because you can,” all while walking in an animated fashion for comedic effect. She then laughs in a deliberately unrealistic manner. Despite these attempts to convey humor, she reveals the stakes in her sharing the pricing discrepancies of the brand she promoted. The brand claims to provide a never-before-experienced world of luxury to the creators in the barter exchange. However, in doing so they deny Mangal’s familial and seemingly naturalized access to the world of luxury.

This speaks to her class and caste-based privilege which manifests itself as capital–aesthetic, cultural, her “taste” (Bourdieu 1984). The mother’s shawl represents more than just purchased luxury. It is a familial, inherited caste legacy and privilege that cannot be evaluated by the brand. In a society where items like “expensive shawls” become part of the marital trousseau of women whose families can afford it, Ishita conveys her inherited capital in coded terms. The brand undermined more than just her alienable labor, it undermined her pedigree as well.

The alignments between labor and capital take on different meanings in an online space that theoretically is accessible to everyone. What are the stakes of claiming or not claiming labor as the explicit site of being a creator on social platforms? In what ways do class, caste, gender circulate as aesthetic and cultural capital carefully curated to seek the attention of the viewer?

References

Dattatreyan, Ethiraj Gabriel. 2020. The Globally Familiar: Digital Hip Hop, Masculinity, and Urban Space in Delhi. Duke University Press.

Marx, Karl. 1952. Capital. William Benton.

Piliavsky, Anastasia. 2020. Nobody’s People: Hierarchy as Hope in a Society of Thieves. Stanford University Press.