This post is part of a series on the SEEKCommons project. Read the Introduction to the series to learn more.

Sugar, particularly that from sugarcane, takes many different shapes and forms in the world. During my research on sugarcane in Brazil, the largest producer of the crop, I started tracking in a spreadsheet all the various forms of sugar or sugarcane I encountered in my fieldwork. I called this my sugar library. The below figures display some examples from the sugar library, grouped into thematic categories and listed without the various metadata included in the spreadsheet version.

Sugarcane growing in/around:

- Yards

- Abandoned lots

- Side of the road or highway

- Fields that stretch to the horizon (“rolling seas of cane”)

- Outside academic labs

- Inside academic greenhouses

- A back-lit vase at an industry summit

- An educational display at the ruins of an old sugar mill and plantation museum

- The Center-South region more than the Northeast

- Not? “Sugarcane doesn’t exist in nature”

Sugarcane before, during, or after physical transformation:

- Cut and ready to be pressed to make juice at the local market

- Being pressed to make juice

- Leftover bagasse (pressed stalks) piled up next to the pressing machine

- Dried and shredded palha (cane leaves) for biochemical analysis, in bottles or bags in the lab

- Brown liquid after pretreatment

- Clear liquid with extracted cell wall carbohydrates

- On fire, being burned in the field (accidentally or intentionally)

- Dried, pinned to a poster at a conference

Things made from sugarcane, its byproducts, its components:

- Biofuels, available at most fuel stations in São Paulo and surrounding regions

- Shoes

- Bioplastic grocery bags, nonbiodegradable

- Air conditioning (via bioelectricity generated by burning bagasse)

- Bagasse (leftover pressed stalks)

- Bagasse hydrolysate

- Palha (straw)

- Flex palha

- Vinasse

- Torta

- Sucrose in the stalk

- Lignocellulose in the leaves

- Sugar

- Sugar as currency

- Sugar as energy supplement

- Raw sugar

- Brown sugar

- Crystalline sugar

- Refined sugar

- Organic sugar

- Light sugar

- Liquid sugar

- Sugar destined for export

- Sugar destined for domestic consumption

- Centrifuged sugar

- Cachaça (liquor)

- Caldo de cana (sugarcane juice for drinking)

- Sugarcane juice for fermenting

- Biogas/biomethanol

- Compostable cups

- Bioplastic packaging

- Rapadura (candy)

- Natural soap and shampoo

- Alcohol gel sanitizer

- Sleeping pads and hiking seats

- Xylitol

- Cane syrup as a vegan alternative to honey

- Sugar-based bioplastic bags holding refined sugar (meta!)

- The potential to make almost any chemical

My initial research focus was on just one of these forms, sugarcane-based renewable bioproducts—like biofuels, bioplastics, and more—being developed in São Paulo, Brazil. However, my attention necessarily widened as I learned that understanding one sugar form like biofuels precisely concerns understanding the multitude of forms sugar may take. This is the case even when such multiplicitous sugar forms seem far removed from plant-based, renewable petro-replacements.

Kinds of sugarcane:

- Scientific cane

- Usina (mill/processing plant) cane

- Supplied cane

- Own cane

- Sustainable cane

- Transgenic cane

- Conventionally bred cane

- 1920 cane

- 2020 cane

- Colonial cane

- Energy cane

- Dozens of varieties commonly in use today

- Cane as model organism

- Cane as not model organism

- Cane as scientific object

- Cane as raw material for the usinas

- Flexcane

- Hybrid cane

- Cane residues as waste

- Cane residues as not waste

- Cane engineered for burning

- Cane engineered for second-generation processing

- Cane that is a “new oil”

- Bioreactor cane

- Biofactory cane

- Cane for sugar and alcohol

- Cane for biomass and bioproducts

- Palha-less cane

- Super cane

- Carbon sink cane

- Center-South cane

- Northeast cane

- California cane

- Louisiana cane

- “In natura” cane

- First-generation cane

- Second-generation cane

- Touristy cane

- Imported cane

- Coincidental cane

- Normal cane

- Creole cane

- Papaya cane

- Sugarcane as solution

- Cana-obrigada (obligated cane)

- Miscane

- Theoretical cane

- Oil cane

Ways of knowing sugarcane/cane as knowledge form:

- Metrics for growth and productivity

- Sketches and drawings by scientists explaining things about sugarcane

- Start-up pitches

- Slide decks

- Conference proceedings

- Daily newsletters from sugarcane consulting companies

- Websites promoting sugarcane

- Infographics about sugarcane production in Brazil

- Flowcharts of conversions of biomass into different products

- Scientific papers

- Close-up images to show diseases and pests

- Growth curves

- Scientists showing with their hands the entanglement of lignin and cellulose

- Diagram of cane’s genetic complexity

- Diagrams of maturation, the movement of sugar through the plant

- Graphs of imports/exports

- Formula for yield potential

- Sugarcane variety nomenclature

- List of sugarcane traits

- Photographs of cane stalk held vertically by a producer in the field to show its size

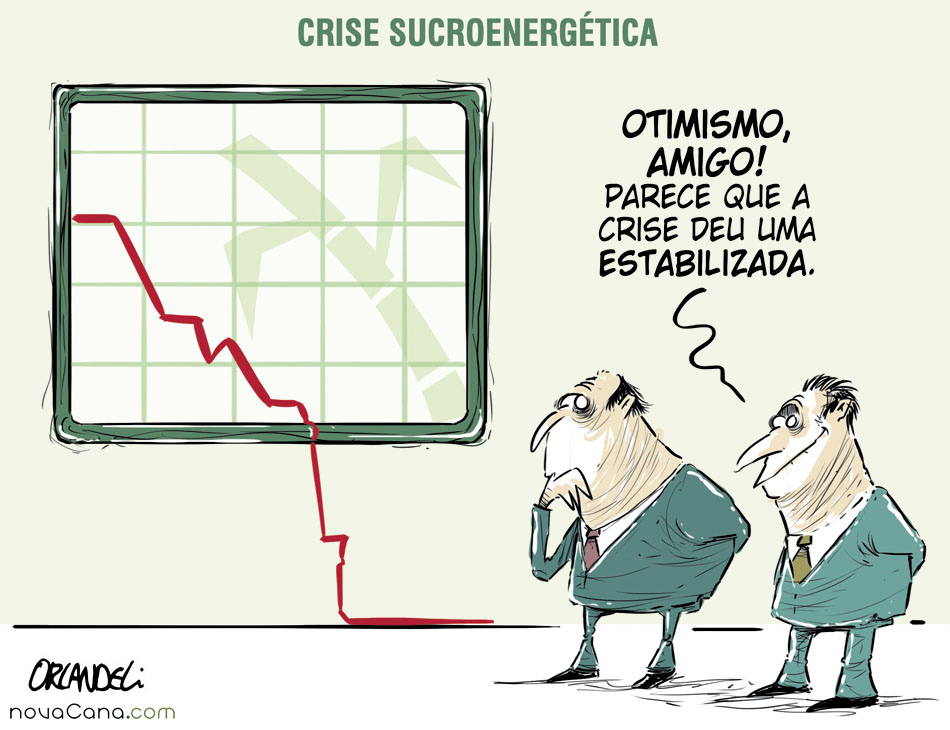

- Political cartoons about the sugarcane sector

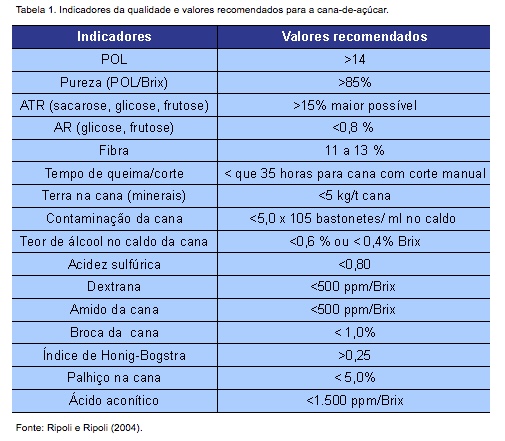

- Tables of percentages of different contents of cane biomass

- Poems about sugarcane written by scientists

- Sugar-alcohol mix ratio

- A free app to calculate your cane productivity

- HPLC peaks

- Beautiful HPLC peaks

- Books about sugarcane, biomass, and bioproducts at university bookfair

- Industry magazines published since the 1930s

- Reports on the industry, both open access and for paying clients

Technical and scientific practices related to sugarcane:

- Mechanized harvesting of cane (almost 100% in Center-South region, though less common in Northeast)

- Xylem staining to check health

- Specific spacing of the cane fields

- Bidimensional and three-dimensional matrices determining when to harvest

- Assay to show carbohydrate degradation

- Manipulating maturation to change the place of sugar in the plant

- CRISPR for genetically modifying cane

- ATE fermentation

- Vinasse recirculation

- Drone-based precision agriculture practices, e.g. to quantify number of plants per hectare

- Bureaucratic processes for approving sugarcane varieties

- Spreadsheet calculators for assessing carbon intensity, for carbon credit programs

- Biomass characterization in the lab

- Pretreatment in the lab

- Enzyme hydrolysis in the lab, as a knowledge tool versus extraction method

- Practices at the usina and by producers to make sugarcane flexible between sugar and alcohol

- Simulators to show usina workers what it’s like to harvest cane

- Automated and manual industrial processes happening simultaneously in the usina (sugarcane processing plant), reflected by the usina’s deafening noise

- ATR as a way to structure producer renumeration

- Using synthetic sugar in fermentation experiments

- Scientific research designs to extract more sugar

- Irrigation—less common in Center-South than the Northeast

In making my sugar library spreadsheet that catalogued the various forms of sugar(cane) I encountered, I had company. To write her novel Out of the Sugar Factory (2023), Dorothee Elmiger was also a collector of sugar forms. “In the folder of ‘sugar’ notes I’m reviewing today, on a piece of graph paper lying among other sheets of key words about sugar beets, sucrose, and the Caribbean plantations, [lies] my handwritten note…,” she writes (Elmiger 2023, 81). She preserved the list form in the novel itself, which reads like one is flipping through these folders of sugar notes scribbled on various sheets of paper. She is explicit about the effect and purpose: “Objects seem to enter into new relationships, new constellations with each other…. Something seemed to reveal itself to me that I couldn’t articulate but could only rediscover in circumstances of similar or analogous structure—as relationships, repetitions, parallels” (11).

Over the course of my fieldwork, my sugar library helped me trace sugarcane’s many constellations, relationships, transformations, and multiplications as scientists and industry actors in São Paulo, Brazil worked to make sugar-based renewables like biofuels and bioplastics. Like Elmiger’s folders, my list of sugar forms mushroomed by the hundreds and I found myself amid unexpected objects and ideas.

Things made possible by sugarcane:

- Thousands of academic conferences

- Future imaginaries, e.g. more sustainable worlds, better worlds

- Sugar futures trading

- Dozens of labs funded by bioenergy/sugarcane initiatives

- Dozens of labs funded by bioenergy initiatives that don’t actually work on bioenergy

- Other kinds of scientific research

- New “state of the art” biomass research centers

- Scientific funding (more than any other thing in Brazil, per one scientist)

- National biofuels policies

- Sugarcane agricultural cooperatives

- Sugarcane consulting companies

- Sugarcane journalism companies

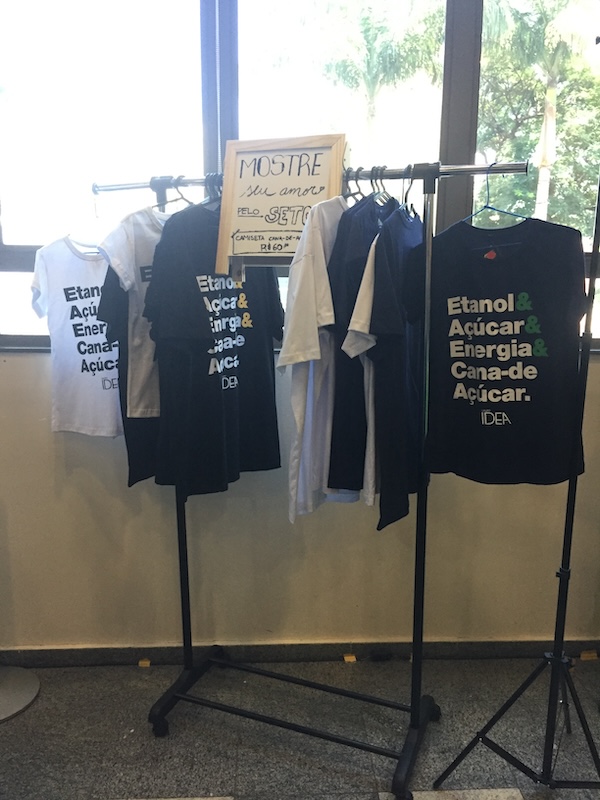

- Merchandise about sugarcane: t-shirts, totes, baseball caps

- Hype videos

- Maturant (ripening chemicals) companies

- Breeding centers/groups

- Fast research trials due to propagation by cutting

- National laboratory not just on biofuels but biorenewables in general

- Potential growth of renewable economies

- “State of the art” combine harvesting machines

- Strong connections between academic research and industry applications in Brazil

- Weak connections between academic research and industry applications in Brazil

- Other biotechnology

- Road named after sugar

- Whiteness of scientific and industry knowledge-production spaces (e.g. conferences) related to sugarcane

- Poems, songs, books about sugar in Brazil

- Art installations

- Playing “California Dreamin’” at a government event on the national biofuels policy

- Playing the national anthem at an industry conference

- US biotech companies opening operations in Brazil

- Anti-black state policies of industrialization in São Paulo in the 19th and 20th centuries

- Training of science students

- Collective prayer before lunch at a sugarcane field day in Louisiana

- Memes

- Agriculture influencer Instagram accounts

- Research centers, private or belonging to universities, out in the middle of cane fields

- Museums and educational displays

- Living museums of cane varieties for educational purposes

- Scientific prestige and attention of the international scientific community

- Relationships between universities and research centers and usinas

- Separation between universities and research centers and usinas

- Convention centers co-sponsored by the state and usinas

Personal connections to sugarcane or general knowledge about it:

- Family owns/owned fields

- Memories of raining ash

- Experiences using flex fuel vehicles powered by sugarcane biofuels

- Ideas of regional differences in knowing cane

- Historical narratives of cane, including its role in colonial slavery and violent, racialized labor practices since then

- Connotations of cachaça

- Memories of the comfort of sucking on a cane stalk

- Nostalgia for the smell of pressed cane

- Sugarcane’s reputation

- Familiarity of cane because of its “500 years” of history

Absences of sugarcane:

- From historical narratives of the country, sometimes

- From journalism on deforestation in the Amazon

- From lab benches of labs funded by sugarcane grants

- From narratives by US biotech companies with operations in Brazil to access cheap sugarcane

- Absence of witnessing sugarcane labor during a conference-sponsored tour of a usina (sugarcane processing plant)

The wide-ranging constellations, relationships, transformations, and multiplications around sugarcane became one of the central premises of the project: when scientists work to transform Brazil’s millions of acres of sugarcane into bioproducts, they indeed do much more than convert sucrose into ethanol, polyethylene terephthalate (PET), or other molecular forms. They also transform sugarcane into a variety of phenomena, ideas, and visions for the future—for example, notions of what a raw material is, sensibilities challenging the conventional instrumentalization of scientific knowledge, and techniques for turning sugar into oil not only molecularly but politically. In fact, making bioproducts is frequently not what my scientist interlocutors mostly do in actuality.

I’ve written about what this means for renewable futures and science elsewhere. In this post, I discuss a new stage of the sugar library’s life: after deploying it as a methodological and analytic tool within my research and writing, I’ve now been working to convert it into an open online repository that other researchers can access and use.

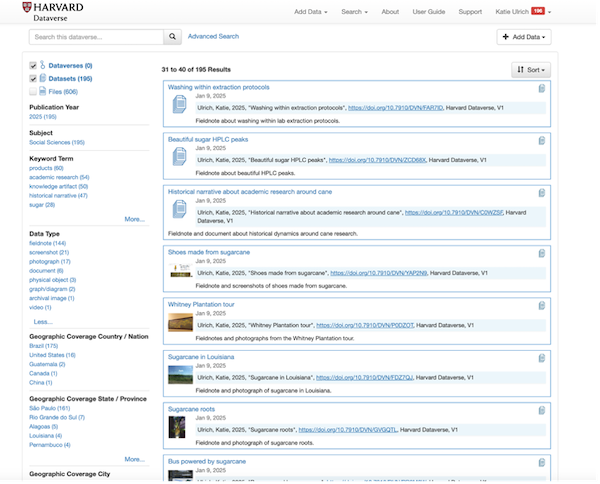

Screenshot of the sugar library on Dataverse (https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/sugarlibrary).

The making of the online sugar library has unfolded amid growing discussions around Open Science, increasing concerns about AI training on stolen materials accessed online, and in the context of anthropology’s fraught history obtaining and distributing others’ knowledge without their permission. Which is to say, it was never a given how and why to share the sugar library as an accessible online repository.

I’ve undertaken this work with the help of a fellowship with SEEKCommons, a project considering the role of Open Science within socio-environmental research, and collaboration with EMERGE, a collective of ethnography labs and studios exploring different modalities of shared/sharing ethnographic research and analysis. Thinking alongside these colleagues helped me more intentionally interrogate the how and why of developing the sugar library as an online repository.

When I initially started researching online platforms and tools to potentially host the sugar library, I quickly learned that the library’s format and its anticipated uses would intimately shape each other. On the one hand, I was interested in the sugar library as a teaching tool, for example to guide students in understanding the multiplicity of meanings and material forms that something like sugarcane, a seemingly basic commodity crop, takes in the world. On the other hand, I wondered if other researchers might find some of the artifacts interesting within the context of their own work. And I was also curious about the sugar library as a site or mode of ongoing engagement with my interlocutors, sugarcane scientists in São Paulo. The spreadsheet version of the sugar library had already served as an elicitation device in my interviews, with some friends and interlocutors even sending me their own artifacts—the sugarcane straw they used to roll a cigarette, a shoe purchased that was unexpectedly made from sugarcane-based plastic.

Some of the online platforms I was exploring, like StoryMaps, Twinery, Scalar, PECE, and Digital Data Stories, would have been well-suited for a narrativized guide through the library, helping make it more engaging and structured for a student audience. Other platforms, like Zenodo, would have prioritized cataloguing and preserving the artifacts and their metadata, making the sugar library entries findable within a wider context of research data. Sifting through many platform options, I also thought about how the sugar library is currently in English, and considered different platforms’ possibilities for displaying Portuguese as well. I came to realize that a given format or platform would likely not serve all potential uses of the library at once. The hardest task became deciding what purpose and format to prioritize.

I ended up going with what felt most achievable and open-ended to start: uploading the sugar library to Dataverse. Each artifact is associated with metadata and keywords that allow one to search or browse by geographical location, artifact type (fieldnote, photograph, physical artifact, document, etc.), unit of analysis (object, individual, text, organization, event), and thematic categories (historical narrative, different kinds of cane, sugarcane products, art, legal/policy, harvest, extraction, and dozens more). In this format, the sugar library might prove interesting or helpful to other social scientists or humanities researchers investigating myriad topics from resource extraction to agriculture to commodities to biotech. Notably, the Dataverse sugar library does not have any narrative structure. It does, though, provide DOI links that could be used in future narrativized versions. For example, I imagine a separate teaching tool that takes students through a choose-your-own-adventure-style online journey, following a sugar molecule as it undergoes numerous chemical conversions and social transformations. (This further develops an earlier experimental draft I created on Miro.) The Dataverse DOIs could be linked throughout to provide additional information. I hope to develop this teaching tool sometime in the future. I also hope to complete a Portuguese version of the sugar library.

Sugarcane bagasse (pressed stalks). Photo by author. https://dataverse.harvard.edu/file.xhtml?fileId=10784548&version=1.0

Sugarcane-based plastic grocery bag. Photo by author. https://dataverse.harvard.edu/file.xhtml?fileId=10784442&version=1.0

In the meantime, the Dataverse sugar library can still serve as a methodological example of approaching multiplicitous objects like sugarcane, those that sit at the seeming center of gravity of numerous other processes and social structures. It models the gathering of artifacts that one might have never thought to find in relation to an object, bringing them into the scope of analysis when they previously remained on the periphery. For me, certain artifacts and juxtapositions of items in the library generatively unsettled my inherited conceptual frameworks about cane and science, showing me how scientists craft not bioproducts as much as pathways for (re)imagining social change amid climate change. Maybe the sugar library will do so for other researchers or students too, or prompt something similar in their own work.

Metrics relating to sugarcane productivity. Source: Ripoli and Ripoli 2004. https://dataverse.harvard.edu/file.xhtml?fileId=10784798&version=1.0

T-shirts promoting the sugarcane industry for sale at an industry conference. Photo by author. https://dataverse.harvard.edu/file.xhtml?fileId=10784634&version=1.0

I see the Dataverse version of the sugar library, then, as a first step in experimenting with sharing ethnographic data in some other form than polished journal articles or books. The sugar library builds on how many anthropologists and other ethnographic knowledge producers have long explored expansive modalities of ethnographic knowledge production and sharing, including activist and applied anthropological work, as well as work by people bridging disciplinary perspectives and norms. See, for example, EDGI, the Asthma Files, A Field Guide to Oil in Santa Barbara, the Puerto Rico Syllabus, the San Joaquin Valley Toxic Tour, Metagoon, Animals as Objects, and the Feral Atlas.

Processed sugarcane straw in the lab. Photo by author. https://dataverse.harvard.edu/file.xhtml?fileId=10784822&version=1.0

Satirical cartoon about the sugarcane industry. Source: NovaCana.com. https://dataverse.harvard.edu/file.xhtml?fileId=10784804&version=1.0

After all, ethnography has always challenged any simple distinction between data, analysis, and “findings.” Alberto Corsín Jiménez (2021) spells out ethnography’s “nature as an archive; as a memory practice, a circulatory economy, a system of distributed authorship; and as an infrastructure of rights, permits, and obligations. It involves tracing the material journey of ethnographic effects from our fieldwork notes to our evening reflections and back again; from the insights or intuitions annotated in a rush on the margins of our notebooks or in Evernote to the drafts we share with our interlocutors in the field, as well as the drafts they share with us” (130-1). It thus makes sense that our modalities of sharing our work with others will continue to exceed the conventions of published articles and books, or even open data sets and preprints.

Sugarcane in Brazil. Photo by author. https://dataverse.harvard.edu/file.xhtml?fileId=10785148&version=1.0

Someone asked me recently when I stopped adding items to the sugar library. I used the publication of the Dataverse collection as a cut-off, though new items had already slowed to a trickle after I stopped the most intensive phase of my research. The sugar library is contingent and enacts situated knowledge (Haraway 1988). This approach doesn’t assume that completeness yields the best chance at understanding the phenomena we study, nor that completeness is even possible. The sugar library has little of what one perhaps might expect to find in a library of artifacts about sugarcane in Brazil—entries relating to deforestation, or the labor of cultivating and harvesting cane, or its histories of slavery, racialized violence, and Black and Indigenous resistance. Instead, the library gathers items that were harder to anticipate, like the dozens of different kinds of cane that were meaningful to people, from touristy cane to theoretical cane; “living museums” of cane; and the wide range of other scientific research projects done in the name of sugarcane biofuels. This is central to what I see as the political project of the sugar library, in all its forms and versions. Silences within archives are productive (Trouillot 1995). The tension between the library’s relative lack of entries about those aspects of sugarcane’s social lives one might expect and its surfacing of other items made hard to imagine is the productive engine of my research project: both are each other’s conditions of possibility, analytically as well as ethnographically.

Explore the sugar library here.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the SEEKCommons fellowship (NSF grant #2226425). I am very grateful for the insights and support from many people who have helped me construct the online sugar library: the OEDP and SEEKCommons teams (NSF grant 2226425), especially Gerd Herber, Michelle Cheripka, and Luis Felipe Murillo; the EMERGE community, particularly Marcel LaFlamme; Katie Mika and Matt Cook at the Harvard University Library; Mary Pandergast, who provided an archaeological perspective; Sarah Kelly and my cohort at the 2024 Dartmouth Energy Summit; and Andrea Ballestero and the Expanding the Social World Downwards project. I also thank Keren Reichler and Michelle Venetucci for invaluable feedback on an earlier draft of this post. My research has been supported by the National Science Foundation (BCS-1918156 and 1842494), Rice University, Haverford College, the Brazilian Studies Association, and Harvard University.

References

Corsín Jiménez, Alberto. 2021. “Ethnographic Drafts and Wild Archives.” In Experimenting with Ethnography: A Companion to Analysis, eds. Andrea Ballestero and Brit Winthereik. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Pp 123-132.

Elmiger, Dorothee. 2023. Out of the Sugar Factory. Trans. Megan Ewing. San Francisco, CA: Two Lines Press.

Haraway, Donna. 1988. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14(3): 575-599.

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. 1995. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston: Beacon Press.