One early morning in August 2024, I boarded a coach bus in downtown San Francisco. We drove over the Sierra Nevada Mountains, past Reno, and through the Pyramid Lake Paiute Reservation. After six hours, the bus entered the Black Rock Desert and arrived at Burning Man: an annual, week-long event where 63,000 “Burners” create a temporary city dedicated to art, self-expression, decommodification, and self-reliance.

My bus pulls away from the Playa. Image by author.

I went to Burning Man as part of my ethnographic research on AI development in the Bay Area. I had never been before, but many of the AI developers I met identified as Burners, and they urged me to join them. Curious about what they found there, and in the mood for some adventure, I accepted their invitation.

I prepared by gathering camping gear and reading tech historian Fred Turner’s essay about the event (2009). In this essay, Turner argued that Burning Man’s “sociotechnical commons” and DIY ethos offer tech workers a meaningful and relatively unalienated experience of technical labor and its products. To this end, Burning Man legitimizes the ideals and techniques of new media production, serving as a “cultural infrastructure” for the Bay Area’s tech industry.

Turner’s experience at Burning Man occurred at the height of the Web 2.0 era, when online platforms proliferated and startups like Google were icons of Silicon Valley. Today, Silicon Valley leaders depict generative AI as equally, if not more, transformative than the internet, and Google, though it embraces generative AI, now faces challengers like OpenAI. In this changed context, I wondered how my experience would compare with Turner’s. Which aspects of the Silicon Valley ethos would my time in the desert, which Burners call the Playa, bring to attention?

During my week at Burning Man, I saw first-hand how the event can legitimate Silicon Valley’s social organization and creative ideals. But in light of my field work on AI, I found another resonance between the Playa and the Valley: civilizational ambitions. I see Burning Man as a simulation for building a new civilization—a new way to organize society, the self, and, as media theorist John Durham Peters (2015) adds, our society’s relationship with the natural world. This resembles claims I heard from AI developers about the technology’s own promises of civilizational transformation—of enabling new, even alien forms of society, self, and environment. This is not to say that Burning Man trains AI researchers to adopt such ambitions; rather, I suggest a commonality in ethos that may appeal to my interlocutors’ tastes and one that may grow from shared roots in the Bay Area. In this civilizational aspect, Burning Man’s environmental experience becomes especially important, and it is this experience that I will now describe.

Playafication

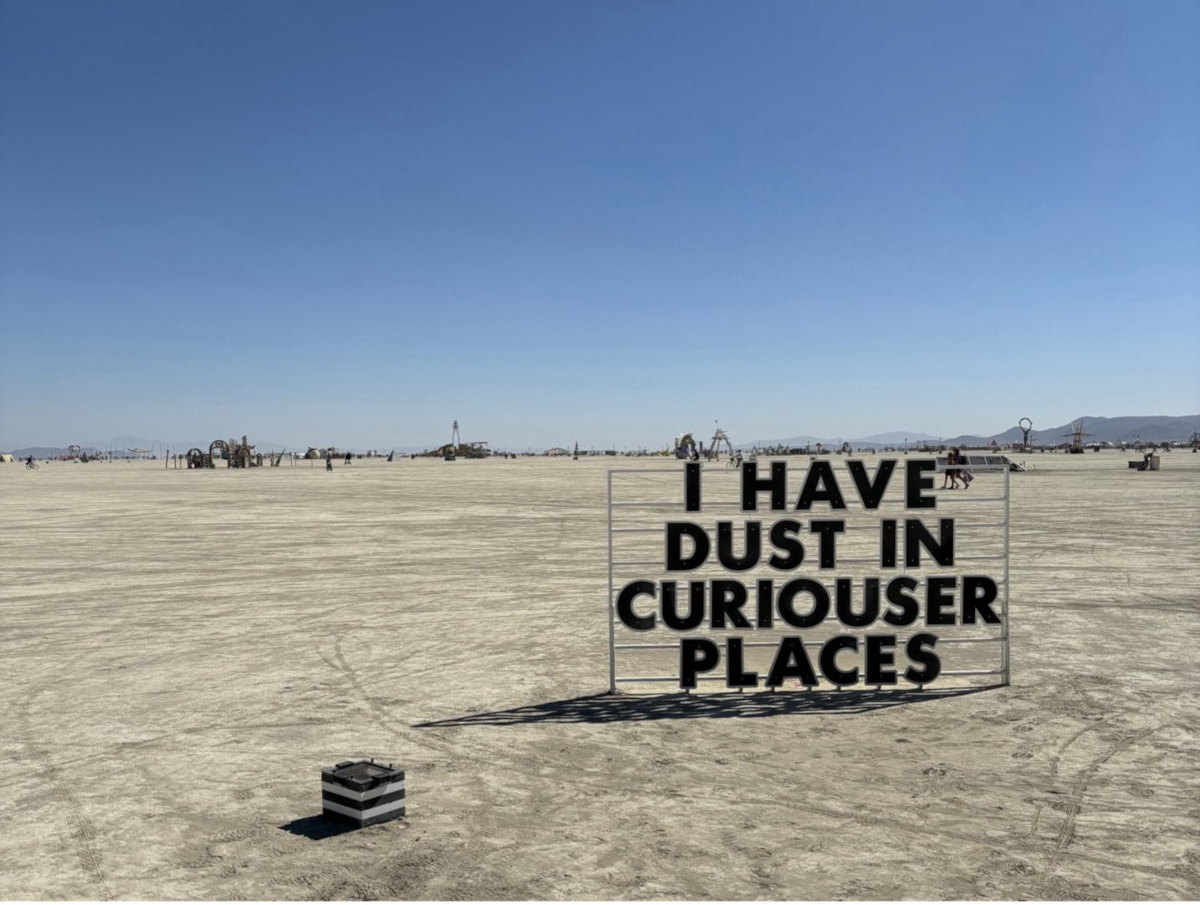

Upon our arrival to the Playa, my bus mates and I were greeted by volunteers. Shouting through megaphones, they summoned all first-timers for a ritual. They instructed us to throw ourselves onto the ground and create “dust angels” by waving our arms and legs in the dust. We would effectively coat our bodies with the fine, alkaline particulate that fills the Black Rock Desert. “You’re gonna get dusty anyways, so you might as well get it over with now!” they reasoned. After working up the courage, we each took turns bathing in the dust. Next, we approached a large bell, set an intention for the week, and struck it with a piece of rebar. The resonance marked our official induction as Burners. Over the course of the week, we became more comfortable with our new status, learning the community’s terminology, traditions, values, and history. We were “playafied,” as Burners call it, not only culturally but physically, as the dust accumulated on our bodies and belongings and remained there for the week. We learned to accept the dust as a matter of course on the Playa.

There’s plenty of talk about matter at Burning Man. The festival has strict policies around cleaning up after oneself, removing all MOOP, or “matter out of place,” in an attempt to preserve the desert. MOOP may be a Burner term, but it should sound familiar to many anthropologists: in Purity and Danger, Mary Douglas (1978) defines dirt “as matter out of place.” Dirt is not dirt because of its inherent composition, she argues, but because it doesn’t belong according to the cultural worldview in use. My default sensibilities led me to initially perceive dust in the same way, but that changed when, after I once described my tent as increasingly “dirty” to a veteran campmate, they swiftly responded: “that’s not dirt, that’s dust!” At Burning Man, dust is not matter out of place; instead, it’s the matter that makes the place.

Playa art by Scott Capernicus. Image by author.

The Playa at dawn ft. the Golden Gate Bridge. Image by author.

Indeed, the dust makes for quite a unique and dramatic place. The Playa is hostile to human life—in addition to the alkaline particulate that fills the ground and air, there is no natural shade or water, and temperatures exceed 90°F by day and dropped to the 40s at night. The conditions challenge the body, and by the end of this year’s Burn, many of us, myself included, experienced hoarse voices, cracked skin, and even bloody noses.

To survive in such conditions, humans must rely on technology. To flourish on the Playa—which is really the goal—even more technology is required. All 1,500 camps must build their own systems for water storage and distribution, waste management, food preservation, and shelter. To bring their artistic projects to life, they add intricate props, lighting, and audio-visual equipment. Building this takes immense effort and begins off-site months before the event. One friend, a San Francisco-based software engineer, helped construct his camp’s water system. He and his campmates designed a network of pumps and monitoring devices to ensure a steady supply of water for drinking, cooking, and washing. They built its components in the preceding months and assembled the system on-site one week before the Burn. They, as did members of my camp and others, built impressive, often climbable structures from wood and metal tubing to create a relatively comfortable, communal, and inspiring living environment. Some camps created fully immersive experiences: take Golden Guy Camp, for example, which built a passage of small bars inspired by the well-known Tokyo alleyway of the same name.

Learning new skills is central to the Burning Man experience. There’s even a designated section about it in the annual Black Rock City Census, an ongoing research project seeking to better understand the community. In the 2023 census (and again this year), respondents were asked if the experience inspired them to acquire new skills. They confirmed picking up skills in art creation/crafting (59%), survival skills (38%), carpentry or metal work (18%), electrical engineering (15%), and construction or mechanical work (14%). Experiencing the products of these skills makes up much of the festival’s day-to-day activity. In camp, we would make use of the infrastructure we built to support one another, and day and night, we would explore other camps and their impressive constructions. When asked about one’s camp, it’s customary to boast about what it has built and what experiences it offers. It’s a way of inviting people in and sharing the products of the camp’s labor.

In the “default world” (as Burners often call their lives outside the Burn), many tech workers build products and systems over which they have little control or ownership. They rarely experience the full extent of their creations’ uses or impacts. On the other hand, Burning Man offers these workers a rare opportunity to engage in technical labor that directly and consequentially influences the world they inhabit. This labor sustains and enriches their own lives and the lives of their temporary community. During the Burn, they can live in a world they and their peers designed and produced. Fred Turner references much of this in his own account, and from my own experience, I must add that the intensity of the dust increases the intensity of this experience; it raises the stakes, consequences, and potential of tech workers’ labor on the Playa.

Dust, Sea, and Space

Insofar as human life requires technology to survive in the dust, the Playa shares common features with the open sea and outer space. Historically, exploration of these latter domains has been particularly stimulating for technological development. In The Marvelous Clouds, John Durham Peters (2015) provides a list of nautically cultivated techniques: “navigation…mapping, timekeeping, documentation, carpentry, waterproofing, provisioning and preservation, containerization, division of labor…fire control…alarm calls, and political hierarchy. Even nutrition.” Space travel has adopted many of these techniques, furthering them through advancements in fields like propulsion, energy storage, materials engineering, computing, and communications. Even the cyborg concept originally responded to the challenge of sustaining human life in space (Clynes and Kline 1960). With their inherent technicity, it’s no wonder why space exploration and sea-steading are increasingly popular fascinations in Silicon Valley.

Burning Man camps employ many of the aforementioned techniques, applying them to life support, construction, and social organization in the dust. And with these techniques, it also adopts the imagery and metaphor of sea and space travel. For example, this year’s ticket featured an astronaut standing on a rocky alien surface with a UFO flying above. Some camps built geodesic domes to house their facilities, and some artists incorporated extraterrestrial scenes into their work. Others adopted nautical references like a life-size shipwreck. The event’s many art cars or “mutant vehicles” took similar cues: space shuttles, yachts, a flame-throwing octopus, and even the Golden Gate Bridge. These dustcraft, so to speak, descend from seacraft and spacecraft.

The 2024 Burning Man entry ticket. Image by author.

Planetary Playa art (artist unknown). Image by author.

Beyond the aesthetics, Burning Man simply feels like being at sea and in space. Most Burners traverse the open Playa with bicycles and art cars, hopping between artworks and musical performances. At night, the darkness obscures the dust and blurs the boundary between land and sky. Standing becomes floating and driving becomes sailing. The dust can reflect the lights of LEDs and flames in ways that resemble a lunar surface. Gusts of wind mimic ocean gales, and the temperature drops evoke the chilling vacuum of space. Each location becomes its own world, separated by void. One might as well be crossing an archipelago or constellation. The Playa, like sea and space, invites exploration. Every morning over breakfast, we would report our findings from the previous night, exchanging them for tips on new sites to visit during our next voyage.

The Playa at night. Image by author.

Peters argues that the ship, “the first completely artificial environment for human dwelling, is an allegory for civilization” (2015, 104). Beyond their means of navigation, ships must carry their own systems for supporting and organizing the life within them. They form a self-contained world separated from their home civilizations by an alien environment. Spaceships extend this allegory, bringing it into a science-fictional future. Situated somewhere between a past at sea and a future in space, Burning Man offers a version of this allegory, too, and in a form that can be experienced not only in the present, but in a place that, while alien, is for many participants less than a day’s travel away. In this light, the material and social engineering at Burning Man becomes a project of simulating a new civilization—indeed, a sandbox civilization.

Deplayafication: From Burning Man to Artificial Intelligence

After a week on the Playa, it was time to take the bus home. Dust clung to my body and my belongings, imprinting itself on everything I touched. The bus sported plastic garbage bags on its seats in an effort to keep them dust-free—a measure I found practical but mildly humiliating. When carried into the default world, the dust was now out of place; it had become dirt, and I had become dirty. Burning Man’s final challenge, then, is “deplayafication”: the removal of dust from oneself and one’s belongings, along with reintegration into one’s network for family, friends, and coworkers. My camp mates warned me of the physical and psychological difficulty of this process. The “default world,” they added, may present itself as stranger and more alien than the Playa world in which I had grown comfortable.

As I returned to my main field site in San Francisco, however, I continued to observe civilizational ambitions of the kind I found on the Playa. Today, AI is not just a purported thinking machine; it’s also a machine to think with—often on a civilizational scale. When AI researchers and engineers work on the latest machine learning models, they grapple with the speculative implications of their technologies for the future of humanity. The changes they envision do not simply entail new ways of completing one’s daily tasks, but rather a complete reorganization of one’s society and species, including the potential to bring it into space. For many observers, the civilizational ambitions of AI developers are either empty hype or far-fetched hubris, but AI developers hold them seriously, and they develop and debate complex worldbuilding scenarios and science fiction stories to model the future they imagine themselves building. Just like these cultural practices, Burning Man depicts alternative forms of human life—this time, in an immersive environment. As it so happens, this year’s official Burning Man theme is Tomorrow Today: “an invitation to imagine the future in new ways, and to make it real through our collective actions.” Soon, Bay Area AI developers will return to the Playa and play in its sandbox civilization.

This post was curated by Contributing Editor Michelle Venetucci.

References

Clynes, Manfred E, and Nathan Kline. 1960. “Cyborgs and Space.” Astronautics, September.

Douglas, Mary. 1978. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Peters, John Durham. 2015. The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media. Chicago ; London: the University of Chicago Press.

Turner, Fred. 2009. “Burning Man at Google: A Cultural Infrastructure for New Media Production.” New Media & Society 11 (1–2): 73–94.