In Val Verde, California, an unincorporated community just a few miles north of popular amusement destination, Six Flags Magic Mountain, it is possible to glimpse the top of the world’s tallest and fastest roller coaster – The Superman- from nearly anywhere. Another, less popular, but arguably as important site lies even closer. Chiquita Canyon Landfill, claiming the designation of second oldest landfill in Los Angeles county, has its official property boundary less than a mile from the western edge of Val Verde. When I lived there in 2013, Six Flags Magic Mountain and Chiquita Canyon landfill were landmarks, one towering in the distance and one burrowing beneath, both at the edge of perception.

My interest in Chiquita Canyon and the community of Val Verde grew out of my involvement with the community opposition to the landfill expansion in 2017. Now, as an anthropology student, my focus has shifted to how the sensory experience of Chiquita Canyon is interpreted, classified, regulated and elusive to regulatory agencies, community members and landfill operators and how these experiences come into conflict. Community members can use odor complaints filed through regulatory agencies to argue the case that the landfill is causing harm. These odor complaints, however, are highly contested by landfill operators as it is difficult to prove that odors are coming from the landfill as opposed to another source. My research asks questions about how odors are articulated in regulation, focusing specifically on Rule 402 from the Air Quality Management Department. While odor is a subjective sense, it is also integrally intertwined with how some people experience their environment (Dżaman 2009; Heaney 2011; Sakawi 2011). The regulation of odor at Chiquita Canyon landfill and other waste sites has proved to be difficult to administer. How do these odors prove that landfills are not contained but inherently porous and border defying?

Image of Chiquita Canyon Landfill in 2017, looking east from Val Verde onto the landfill. Image by author.

Val Verde sits in a valley and has one road in and one road out. Occupying less than 3 square miles of coastal sage scrub and chaparral habitat, it lies at the bottom of the Topatopa Mountains. I give these markers as a way of thinking about Val Verde as contained, insulated, in a sense, hidden. Perhaps this was what drew Sidney P. Dones there. Dones was a wealthy real estate developer in the early 20th century who founded Val Verde, or what he called “Eureka Villa”, as a resort area for African Americans in the 1920s. The development of Eureka Villa was a direct response to the racial segregation of the public beaches and resort areas in Southern California and many other parts of the country. When the town was founded in 1924, it was considered a resort community and dubbed by some as “the Black Palm Springs” (de Graaf et al. 2006). In 1939, Los Angeles County and Works’ Progress Administration built a community center and a park which included tennis courts, baseball fields, an olympic size swimming pool, amenities which attracted the likes of Hattie McDaniel and Norman O. Houston. These efforts sparked community events like a beauty contest, parades and other gatherings. When laws began to change in the 1960s, the demographics of Val Verde began to change too. When I moved to Val Verde in 2013, the local population was mostly young white and Latinx families, students and some retirees who liked to gather at the community center for bingo and didn’t mind discussing the weather or the landfill on any afternoon.

The relative remoteness and isolation of Val Verde, what was at first an asset for early residents, then became its attractiveness to Waste Connections, the parent company of Chiquita Canyon, when the decision was made to site a landfill there. There has been extensive scholarship on the connection between environmental harm and race, proving that exposures to pollution and other environmental risks are frequently distributed unevenly (Mohai 2009; U.S. General Accounting Office 1983; Chavis and Lee 1987; Bullard 1996; Nixon 2011). A study done in 1983 by the U.S. General Accounting Office showed that waste sites in the Southern U.S. were disproportionately sited next to African American communities (U.S. General Accounting Office 1983). In 1987, the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice’s study “Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States” showed that race was the most important factor in predicting where waste sites would be located (Chavis and Lee 1987).

Chiquita Canyon landfill opened in 1972 and so far, I have not been able to find much about the community reaction to the landfill at that time. In casual conversation with local residents, I’ve learned that many people who have moved to Val Verde don’t know about the landfill until it is too late. The landfill becomes perceptible not through sight but through the sensory experience of being close to it over a period of time. Chiquita Canyon and Val Verde have been entangled in many ways over the years. Free dump days, Adopt-A-Highway initiatives and an Annual Bike Build for Youth are some of the ways the landfill has tried to “give back” to Val Verde while also petitioning the county for new expansion permits and violating existing ones. In the book “Fractivism: Corporate Bodies and Chemical Bonds” by Sara Ann Wylie, the author writes about how PR strategies adopted by cigarette companies parallel those used by fracking companies (Wylie 2018, 69). These same gestures, staging public events, the generation about scientific doubt towards air quality and the negative impacts of living close to a waste site, have been employed by Chiquita Canyon LLC.

Val Verde residents have voiced their concerns about Chiquita Canyon over the years, repeatedly focusing on the issue of landfill odors and potential toxic particulate matter that floats the short distance from the landfill to their homes. All of this came to a head in 2023 when the landfill began experiencing an exothermic chemical reaction, or fire, deep inside an old cell of the landfill. This reaction caused odors to increase dramatically and generated tons of toxic waste that the landfill had no way of disposing of . The landfill closed in January of 2025 after a massive intervention by the EPA as well as other local agencies but the problem persists. Wylie also notes the lack of data produced by chemical companies (Wylie 2018, 72) which is reminiscent of Chiquita Canyon’s refusal to perform a “root cause analysis” to determine how the most recent chemical reaction started, leaving room for another reaction to occur at any moment.

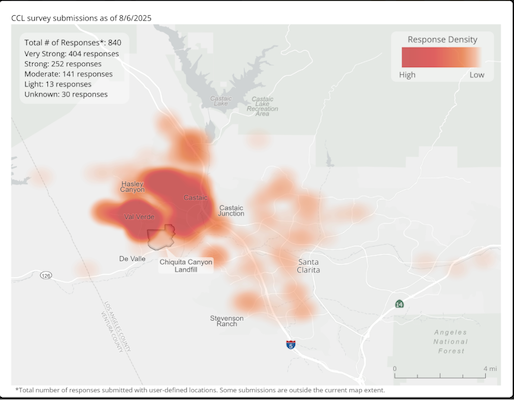

Heat map produced from data collected by the Los Angeles Department of Public Health showing where survey respondents indicated they experienced odor. Dark red areas represent the highest number of responses, lighter orange indicates less responses. This graphic depicts where respondents have smelled odors, not their severity. These submissions are reflective of responses up until 8/6/2025. Heat map produced from data collected by the Los Angeles Department of Public Health showing where survey respondents indicated they experienced odor. Dark red areas represent the highest number of responses, lighter orange indicates less responses. This graphic depicts where respondents have smelled odors, not their severity. These submissions are reflective of responses up until 8/6/2025. Taken from the Public Health website.

The landfill repeatedly defies containment and interferes in dominant conceptions about waste management. I have spoken to regulators and landfill operators who believe that landfilling is still best practice for household waste and yet admit that it is deeply flawed and often harmful to local populations and the environment. In their article “Containment and Leakage: Notes on a General Containerology” Olli Pyyhtinen and Stylianos Zavos set out to explore the ontological condition of containment and develop a theory of containment technologies by way of leakage. Containment and leakage, while often imagined as oppositional, are in their view, co-constitutive. At Chiquita Canyon Landfill, each compartment of waste is fitted with a series of pipes designed to funnel out the gas and liquid that waste generates. This way of managing waste means that landfills are not contained; they emit, they generate, they liquify and ultimately these substances come into contact with human and more-than-human environments. The landfill is made possible by its leakage, its border crossing. From the PVC lined cells, along miles of pipes, leachate and gas flow out of the landfill and into the environment whether that environment is the local community of Val Verde or the larger surroundings. Odor and its resulting effects like headaches, nausea and congestion are one example of how landfill excesses defy regulatory efforts and emphasize how waste may be thrown away but never disappeared.

Thus far, my investigation into measures taken by the landfill to mitigate odors in Val Verde have revealed that environmental regulations often don’t match up with local residents’ lived experience. For example, Rule 402 of the Air Quality Management Department (AQMD) says that “A person shall not discharge from any source whatsoever such quantities of air contaminants or other material which cause injury, detriment, nuisance or annoyance to any considerable number of persons or to the public, or which endanger the comfort, repose, health or safety of any such persons or the public, or which cause, or have a natural tendency to cause, injury or damage to business or property.” The AQMD derives its authority from both federal and state laws, specifically the federal Clean Air Act and the California Health and Safety Code. The AQMD is the primary regulatory and enforcement agency for air quality in California. The “nuisance rule” is widely interpretable and often leaves residents with the burden of proof to show that the landfill has emitted the odors that are causing them all kinds of physical and emotional distress. Other regulations enforced by the Department of Toxic Substances Control, CalRecycle and CalEPA which govern the treatment of leachate, liquid waste generated by the landfill, do little to hold landfills accountable for spillages or mismanagement. As landfill corporations like Waste Connections are billion dollar companies, they can afford to pay or litigate the fines assigned for violations. The years of violations Chiquita Canyon has racked up is exemplary of how landfills can persist with disruptive practices often with little recourse.

Photograph of shoes in the kitchen with landfill dirt taken after a tour of the landfill in 2017. Image by author.

Chiquita Canyon landfill is a landmark for Val Verde residents but less by sight and more by odor. How odor affects landfill adjacent communities is a developing concern as the amount of waste grows exponentially each year around the world. How this odor is interpreted, regulated and managed will have to be taken seriously as the distance between landfill sites and their communities shrinks.

This post was curated by Contributing Editor Ziya Kaya and reviewed by Misria Shaik Ali.

References

Bullard, Robert D. 1994. “The legacy of American apartheid and environmental racism”.Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development. 9(2): 445–474.

Chavis, Benjamin F. and Lee, Charles.1987. “Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States”. New York, NY. Commission for Racial Justice United Church of Christ.

de Graaf, Lawrence, et al. 2006. “African American Communities in California.” Encyclopedia of Immigration and Migration in the American West. Thousand Oaks California: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Dżaman, Karolina, et al. 2009. “Taste and Smell Perception Among Sewage Treatment and Landfill

Workers”. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health. 22(3):227-234.

Fujiwara, Daniel, et al. 2020. “Measuring the wellbeing and health impacts of sewage odour.” Handbook on Wellbeing, Happiness and the Environment: 225-244.

Heaney, Christopher D, et al. 2011. “Relation Between Malodor, Ambient Hydrogen Sulfide, and Health in a Community Bordering a Landfill.” Environmental Research 111(6): 847–852.

Mohai, Paul, et al. 2015.“Environmental Justice.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 34(1): 405–30.

Nixon, Rob. 2011. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Harvard University Press.

Pyyhtinen, Olli, and Stylianos Zavos. 2024. “Containment and Leakage: Notes on a General Containerology”.Theory, Culture & Society 42(2):81-99.

Sakawi, Zaini, et al. 2011. “Community perception of odor pollution from the landfill.” Research Journal of Environmental and Earth Sciences. 3(2): 142-145.

Schweizer E. July 1999. “Environmental justice: an interview with Robert Bullard. Earth First!”. http://www.ejnet.org/ej/bullard.html.

Stokols, Daniel. 2018. Social Ecology in the Digital Age. Elsevier eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1016/c2014-0-04300-6.

U.S. General Accounting Office. 1983. “Siting of Hazardous Waste Landfills and Their Correlation with Racial and Economic Status of Surrounding Communities”. Washington, DC: US Gov. Print. Off.

Wylie, Sara Ann. 2018. Fractivism: Corporate Bodies and Chemical Bonds. Duke University Press eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822372981.