By Beth Reddy and Kim Fortun

Since 2012, the EcoEd Research Group (http://sustainabilityresearch.wp.rpi.edu/k-12-resources/eco-ed-program/) has run over thirty workshops in New York. The group brings faculty and college students (mostly from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute) together with K-12 students in collaborative environmental education. EcoEd workshops have focused on green building, environmental photography, and county-level sustainability assessments, among other topics – engaging both the environment and education in new ways.

Dr. Kim Fortun is an anthropologist and professor in the Department of Science and Technology Studies at RPI, and has been a key participant in the development of EcoEd. I sent her a few simple questions about what EcoEd is up to and how she’s thinking about this kind of work. Her responses, below, touch on issues that won’t be unfamiliar to many CASTAC readers: experiments in ethnography and in the classroom that engage with what Fortun calls “late industrialism” in creative and critical ways.

Fortun: We think through what we have learned about environmental problems – how they play out, the conceptual and cultural challenges they pose – and then try to observe, read about and think through how environmental problems are out of synch with the education and thinking of U.S. kids – so that we can design and deliver K-12 curriculum that speaks to both. It is one way to make ethnographic knowledge “relevant;” it is one of many possible forms of activism.

I run a class spring semesters called “Sustainability Education” that brings new students into the project. We formed the EcoEd Research Group so that those interested could stay involved, and to give me an organizational home for work along these lines beyond the class.

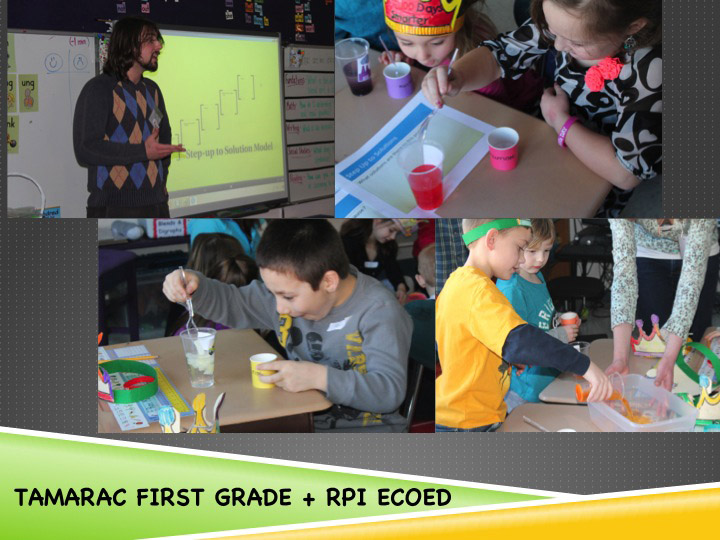

Photos by Kim Fortun and Kelley Fischbach

Reddy: What are your goals within EcoEd?

Fortun: There are many. Most basic is recognition that my research findings – from years of ethnographic work on environmental problems – suggest a need to re-define what counts as scientific, environmental and health literacy. What I’ve called “late industrialism” calls for modes of thought, collaboration and practice that we haven’t yet figured out. Working on this through pedagogy seems grounded, fundamental – and utilizes skills and experience that I have. I always nag my (mostly engineering) students to really think about the kinds of expertise they have and are building – so that they know what they have to share. I’ve thought about the EcoEd initiative in this way.

There are many pedagogical dimensions to EcoEd. One goal is to experiment with ways of teaching university students that pull them into really embodied recognition of environmental knowledge problems and politics. Asking them to consider how contemporary American kids think and are educated really helps with this. Asking them to design curriculum that disrupts and extends how kids think also helps, getting them to think about nano-maneuvers that can shift and open up thinking. The older students become better learners themselves in really thinking about and “engineering” how younger students learn.

EcoEd also experiments with a new kind of collaboration between university researchers and teachers, and K-12 teachers, trying to pull together in creative ways at a time of crisis throughout our educational system.

Photo by Kim Fortun and Kelley Fischbach

Reddy: How did you become interested in this kind of pedagogy?

Fortun: I was raised (so to speak, in graduate school and in my field experience in India) on the critical pedagogy literature, which of course synchs with postcolonial and feminist theory in lots of ways – particularly in concern about marginality: how it is produced, legitimated, sustained; how particular types of people and things come to be ignored, while often depended on and exploited. So I’ve long been interested in habits of mind, and the inevitable exclusions. And in what I’ve come to think of as the double bind of education and expertise: the urgent need to create and codify ways of knowing, while also needing to acknowledge that every codification cuts out some things. Working to understand and engage the many forces that shape how students know, ignore and come to care (or not) about things extends from this.

I’m also committed to continual experimentation with how ethnography can be practiced. A challenge of ethnography, it seems to me, is to be forever on the lookout for discursive fields that deserve “critique,” but also deserve more than that – something that unsettles the field, enabling something new to emerge. K-12 schools certainly deserve more than critique. In the United States, K-12 public schools are both an incredible accomplishment, maintained by many incredibly committed and skilled teachers and administrators, and a real problem – a place where many cultural problems are reproduced.

I’ve come to think in terms of discursive risk – ways of thinking about and representing the world, in very particular and concrete arenas of practice (like K-12 schools) – that interiorize a future that is unjust, or just ignorant (i.e. indifferent to its own conditions). Conventional K-12 education in the U.S. is riven with these kinds of risks. And it is not a failing of K-12 teachers. What I’m concerned with is a broader, cultural failure — to recognize and attend to “the environment” (broadly conceived). Much K-12 curriculum has internalized this; it is going to take combined expertise and commitment to figure something else out. So EcoEd is about research – collaborative research to figure out how we can animate environmental thinking, combining the expertise and insight of K-12 and university teachers, and of students at many different levels. We use what we call a “cascade” model of learning, wherein university students come to really understand the conceptual and cultural challenges posed by environmental problems by really thinking through how to cultivate capacity to deal with those challenges in younger students. To do this, the university students have to think in a deeply ethnographic way – about both environmental problems, and about contemporary kids and schools. I help them think about kids as dosed – with Disney and advertising, with financial concerns and ambitions, with endocrine disrupting chemicals. Then we go meet those kids, curriculum in hand. It is an incredible learning experience for all.

Photo by Kim Fortun and Kelley Fischbach

Reddy: What do you think this kind of project means or could mean for the changing contours of the field of anthropology, particularly academic anthropology?

I have deep confidence that anthropological knowledge is “relevant,” and think we need to be more creative and assertive in sharing it – putting anthropological knowledge into circulation in different arenas. It takes an experimental sensibility, and a good ethnographic eye. You have to do the analysis and critique, and keep looking – staring, often – at your “object of concern” until you find a place where some kind of discursive intervention is possible. This kind of intervention isn’t corrective or persuasive; the anthropologist doesn’t have to know the answer, or have compliant subjects. She just needs to see where a system (of meaning making, for lack of better words) is stuck – “critique” points to this. But good critique also reads what it studies closely enough to see how “the text” works, fails, and has ambivalences that create openings for change.

2 Trackbacks