Today we have a special post from the 2015 Forsythe Prize Committee announcing two scholars recognized in this year’s competition. The Diana Forsythe Prize was created in 1998 to celebrate the best book or series of published articles in the spirit of Diana Forsythe’s feminist anthropological research on work, science, or technology, including biomedicine. The prize is awarded annually at the AAA meeting by a committee consisting of one representative from the Society for the Anthropology of Work (SAW) and two from the Committee on the Anthropology of Science, Technology and Computing (CASTAC). It is supported by the General Anthropology Division (GAD) and Bern Shen.

Winner, 2015 Diana Forsythe Prize

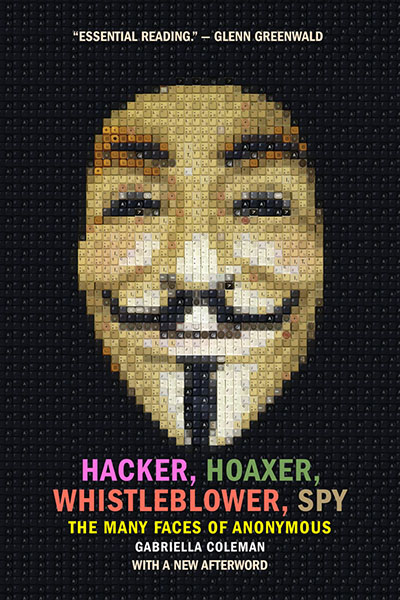

Gabriella Coleman’s Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy: The Many Faces of Anonymous (Verso, 2014) is a powerful ethnography of the making and remaking of networked computational infrastructures and their animating publics and politics. Taking a multi-method anthropological approach to understanding the unruly online collective known as Anonymous, Coleman creatively continues Diana Forsythe’s legacy of getting underneath the cultural logics motivating projects of computational representation and culture. In her unique ethnographic exploration, she tracks affiliated participants across virtual and physical spaces, providing a rich and highly intricate understanding of the labyrinthine worlds that her hacker-activist subjects occupy.

Writing on a much-criticized and often misunderstood technosocial “movement” lacking a fixed or overarching structure, Coleman’s original book deftly navigates the complexities, ambiguities, and controversies of digital forms of activism. At once intellectually rigorous, impressively thorough, and captivatingly readable, Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy speaks to a wide audience with sophistication and nuance, offering highly generative analysis and eliciting multiple readings that bring us closer to (if never overcoming) the contradictions and uncertainties of her subject matter. Where Anonymous have often been demonized or dismissed in popular media, Coleman refuses the “gross fetish of stereotypes” so often mobilized in its characterization, instead astutely reading Anonymous as a new and important kind of political collective exposing and acting against the security state and its attacks on fundamental freedoms.

Throughout the book, Coleman shifts reflexively between numerous roles: an anthropologist studying sometimes-illegal activity; a participant-observer in an online world; a go-between and translator of sorts between the collective and the public. In the process, she offers a timely and immensely relevant contribution to critical contemporary scholarship and public debates on technology, digital worlds, social movements, and incipient forms of politics.

Expertly probing the social, ethical, and political spheres of democracy and voice in our contemporary world, Coleman’s generous approach opens space to consider the new possibilities for politics, direct action, solidarity, and organizing that are too easily erased or distorted. Enchantment, in her account—that of Anonymous, and her own—presents as an ethical and political possibility, a means of sustaining or cultivating hope, a form that works to propel “disruption and change.” For opening new channels of thought into our technological present and characterizing new forms of politics in-the-making, this brave scholar and her vivid book deserve our highest prize.

Honorable Mention, 2015 Diana Forsythe Prize

In Ordinary Medicine: Extraordinary Treatments, Longer Lives, and Where to Draw the Line (Duke University Press, 2015), Sharon Kaufman explores the consequences of the life-extending biomedical and pharmaceutical technologies that have become part of the standard of care for treating conditions that affect millions of elderly people in the United States. Through powerful ethnographic scrutiny, Kaufmann questions what has become accepted commonsense about medical technology, aging, and care and urges us to ask core humanistic questions about who we are, how we want to live, and the kinds of choices and sacrifices we are willing to accept (or not). Writing from within the “postprogress” world of contemporary American health care, the piercing anthropologist grapples with the cultural, political, and economic forces that both shape and are shaped by our expectations, hopes and desires. In so doing, Kaufman’s lucid, sharp and compelling book exposes the hidden logics and systems that structure our present quandaries, and offers new avenues for asking: “how, ultimately, do we want to live in relation to medicine’s tools?”

The lessons of this exemplary ethnography build upon Diana Forsythe’s pioneering ethnographic work on infrastructures of medical expertise, showing us what happens when “life” is valued as a thing—rather than a process—in itself. While debates about health care reform in the United States consistently skirt the question of values in favor of a technocratic rhetoric about efficiency and cost control, Kaufman’s essential work points out that the conjoining of scientific evidence, Medicare policy, and therapeutic imperatives have nonetheless given rise to a makeshift ethical field which significantly impacts familial and self-governance. Her approach to this novel sociomedical reality complicates assumptions of technological rule from above, and grounds market abstractions in lived realities and relations of care. Reclaiming medicine as a social good and a question of values, Kaufman restores the “existential and social” to questions about living and dying amidst the promises and perils of contemporary health care and, in so doing, lives up to anthropology’s highest humanistic and critical goals.

2015 Prize Committee

João Biehl (Chair) (Princeton)

Nina Brown (The Community College of Baltimore County)

Stefan Helmreich (MIT)

[This post has been corrected to show that this is the 2015 prize year, not 2016. — Ed.’s note]

1 Trackback