This is the second in a series of posts by scholars who attended the Anthropocene Campus Melbourne, an event hosted in September by Deakin University as part of the larger Anthropocene Curriculum project. Over the four days of the Campus, 110 participants from 49 universities (plus several art institutions and museums) attended keynotes, art exhibits, field trips, and workshops based around the theme of ‘the elemental’. Read the first post in the series here.

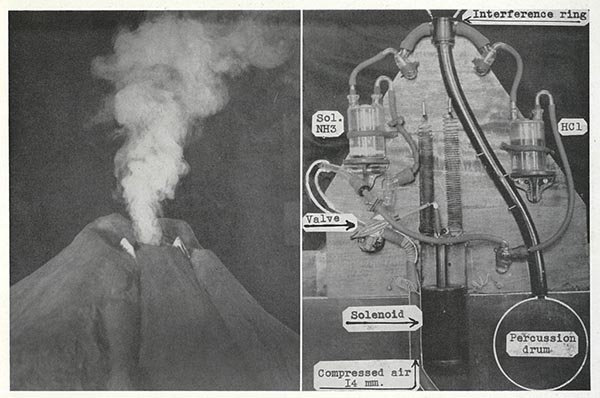

Frank Perret, Chemical volcano model, from Volcanological Observations, 1950.

It is not difficult to recognize the ubiquity of nature forecasting in our world. Every day we hear some claim about the future of nature: what it will do, where its consequences will be felt, and by whom. Not only is mundane weather forecasting integral to daily life, even climate change is structured by experts’ claims about the future of oceans, temperature, and carbon levels. In the early 20th century, when weather forecasts began to share media space with economic digests, even the economy took on the language of weather forecasts and began to be described in terms such as “economic barometers.” The fundamental structures of society began to act like the weather; they too were liable to depressions and tempests.

My intention here is not to make a forecast but to understand the process of forecasting itself. This means understanding how futures emerge and pass away, how they are discarded, mobilized, distributed, and enacted in the present. The future, in this sense, is not self-evidently given but is something that is brought into being; something that is achieved.

Producing Futures

This perspective is certainly not only mine. There has been much work in geography and anthropology dedicated to understanding the social function and production of the future[1]. This work has allowed us to conceive of the ways in which particular futures are mobilized to govern people and space, to pit certain groups against others, to foreclose—and even extinguish—alternative political imaginaries.

The mobilization and politicization of the future operates also on relationships between society and nature. Dangerous, risky, and vulnerable futures are galvanized in relationship to unpredictable and volatile environments in ways that pressurize, speed up, or intensify particular social relations. [2] Think of how populations have been forcibly transmigrated away from volcanoes in Indonesia, or urban floods have been used as excuses to demolish slums in Jakarta. The history of urban housing and property insurance industries cannot be understood without accounting for the long histories of urban conflagrations of in cities such as London or New York. Those cities were dense accumulations of wood, stone, fibers, and open flame that frequently burned and, because of this, gave rise to vast industries that broker futures with the material of cities. Thinking about how the future is political and material in this way has allowed us to understand more broadly how there is never just one future on the social scene but a dense ecology of them vying for attention, coming into being and passing away.

But there is one thing that has been frequently overlooked in this work: the center of the earth. Those of us interested in the social and political function of the future can energize a discussion around cosmology and cosmogony.

Centering the Earth and the Earth’s Center

On volcanoes, or coastlines disappearing under rising sea levels, and at the edge of earthquake cracks and the muddy grounds of landslides, there is obviously an intense relationship between the necessity of forecasting and the need to understand the earth itself. Pressing cosmological problems emerge around the makeup of the earth—its interior, origins, contingency or lawfulness. It is pressing because there are social demands to know what the future holds and these require an engagement with the meaning and make-up of the earth. Nature forecasting at these sites of high levels of uncertainty is a way of doing cosmology because it demands an account of the structure and causes of how the earth works.

But more than this, nature forecasting in these circumstances is also a way of building cosmologies into the world, making them material and giving them form. Cosmologies make worlds in their own image. They are not just interpretations of the world or ideas projected onto the world. The cosmology that states that mantle convection determines crustal movement, the shape of continents, earthquakes and volcanoes, is a product of modern earth sciences, and modern earth sciences are the product of the spaces made by global networks of instruments and laboratories. This is the modern cosmology of the earth, our myth of earth, that is enacted in space in these networks, laboratories and instruments. Forecasting earthquakes, eruptions, and tsunamis, then, becomes material performance of the cosmology of plate tectonics and a means of testing it in the world. In other words, forecasting becomes a way of testing the veridiction of a cosmology. Cosmologies are models of the earth that are built and extended in real space and transform the earth into their own image. Landscapes, then, are these built models made inhabitable and lived in.

The reason that it is important for those of us interested in understanding forecasting to foreground cosmological and cosmogenic questions is because it allows us to dig deeper into the conditions that make particular futures possible and how the time of nature is lived socially. Modernist geology, as historians of geology tell the story, was born of a cosmology that struggled with its Judeo-Christian, monotheist inheritance, and produced not only the astonishing deep past but also the deep future—an earth that will outlast human inhabitation and that was not made for us.[4] This “disenchanted” modernist future is inseparable from a conception of earth and planetary structure developed in the European and American high imperial and colonial periods and of which the Anthropocene designation is the most recent instance of this geological cosmology.

By placing the future of the earth at the center of inquiry we can also begin to think about the stories that describe and explain how the earth operates—its cosmology. This also means taking seriously the multiplicity of cosmologies that haven’t been “modernized,” or otherwise subverted, escaped, or hybridized with contested cosmologies. We can begin to understand how the earth’s futures differ according to the cosmological understanding of what, how, and why it is made. This has consequences for the kinds of political futures we can imagine. We can imagine that multiple futures of the earth—not only deep time—have emerged, been tested, and put into circulation. And because of this, we can also begin to understand how those different futures have forged different kinds of politics and relationships between society and nature.

The future of nature, then, is a cosmological question. Before making claims about what the future of nature will be, I suggest that we undertake the cosmological work on the make-up of earth itself, its origins, and how multiple cosmologies interact as ideas, architectures, and materials in space. This of course also means avoiding the tropes of modernist comparative cosmologies which often imagined that cosmological systems were stable, with defined edges, and without history. Instead, it is a problem of cosmologies in motion and encounter, of space and matter, folded and enfolding. They carve out and test futures of the earth, place the earth under our feet, make sense of its shuddering and displacement. They multiply the earth and its futures.

References

[1] I’m thinking of some of the classic works, including but not limited to, Paul Edwards, A Vast Machine: Computer Models, Climate Data, and the Politics of Global Warming (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2010), Brian Massumi Ontopower: War, Powers, and the State of Perception (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015), Louise Amoore, The Politics of Possibility: Risk and Security Beyond Probability (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013).

[2] On volatile soils and property in Mexico city see Seth Denizen “Baroque Soil: Mexico City in the Aftermath,” on the geopolitics of managing calderas, see Amy Donovan “Politics of the Lively Geos: Volcanism and Geomancy in Korea,” both in Political Geology: Active Stratigraphies and the Making of Life (Switzerland: Palgrave, 2018).

[3] Deborah Coen, The Earthquake Observers: Disaster Science from Lisbon to Richter (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013). For a study of scientists making sense of seismographs and shamans making their own geophysical instruments, my dissertation about Mount Merapi at Cultures of Forecasting: Volatile and Vulnerable Nature, Knowledge and the Future of Uncertainty.

[4] Martin Rudwick, World’s Before Adam: The Reconstruction of Geohistory in the Age of Reform (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2008); Martin Rudwick, Earth’s Deep History: How It Was Discovered and Why it Matters (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2008).

1 Trackback