The dominant disciplinary literature on cultures and practices of extractivism relies on a separation of “the field,” and the insights gained there, from our professional lives as anthropologists in an academy culturally and socially situated in the “Global North.” Increasingly, such distinctions fail to hold as the consequences of extractivism and the conflicts that it produces arrive at the doorstep of the anthropologist’s place of work. I wrote this piece as I grappled with how to frame the effects of toxicity from gold mining in ways that fully accounted for its vast reach beyond “the field” and beyond the material forms (gaseous, liquid, sludgy, in blood levels, as illness symptoms) that I expected it to take. In grappling with the extensive nature of mining toxicity, events occurred to shift my attention to the transnational webs of capital, and the forms of life such toxicity generates. I began to ask: Beyond our accustomed and necessary examination of extractivism’s cultures of technoscience, conflict, and toxic harm, what are the anthropologist’s responsibilities in confronting toxicity as a generative force that collapses the “field” and “home” distinction? What better questions can we begin to ask by centering entanglement, proximity, and relationality in our analysis of the multi-layered nature of corporate toxicity and its profits?

I take Michelle Murphy’s conception of the “alterlife” (2017) and Tiffany Lethabo King’s concept of the “pore” (2019) as entry points to address these questions. Murphy suggests that humans are already transformed, or “altered,” by the chemical entanglements, enmeshments, and connections that our permissive cultures of corporate technoscience and toxicity science allow (2017: 497). Yet Murphy also suggests that we do not limit our analyses to bodies transformed by the corporate use of chemical substances to avoid replicating the tropes of marginalized Black and Brown bodies suffering from the harms of modernity. As expressed by the epigraph, the suggestion is to account for the ways of life, technoscientific cultures, and the broader power dynamics that these bodies in pain concentrate. This form of analysis demands that toxicity be linked to settler colonialism and, though unnamed in Murphy’s text, also to the plantation economy and its afterlife as racial capitalism (Robinson 2020).

King (2019) engages such a critique of toxic ways of living from the vantage point of Black studies by reading material culture and visual representations of Black subjects forced to process indigo on South Carolina plantations. Her argument rests on examining the intricate ways in which Black subjects inhabit a world of “many relations” and the multi-species engagements in which the land inhabits people too. This eco-social inhabiting takes place at the site of the pore: the first point of access between humans, nonhumans, and toxicants. In hands stained blue, King (2019) reads beyond the racialized expectation that Black people labor to make white settler projects of dominating nature possible—and thus become “closer to the Human.” Instead, at the site of the pore, the boundaries and empiricist categories that separate humans, plants, animals, and land become more visible as unstable political projects edging on collapse.

As I argue in this piece, gold mining, toxicity, and the circulation of the profits it generates, not only make visible this collapse but also ethically implicates anthropologists and challenge the very conception of “the field.” Before arriving at this entangled space, I want to center the social life of toxicity and conflict in my field site, the Dominican Republic.

Cultures of Knowledge and Representation in Conflict

Bird’s eye view of the Pueblo Viejo mine. Image from Barrick Gold Corp.

During the first few weeks of April of 2021, residents of the municipality of Yamasá, in the Monte Plata Province located in the center of the Dominican Republic, learned through word of mouth and social media that the Canadian mining corporation Barrick Gold had begun offering free guided visits to its Pueblo Viejo mining installations for anyone who was interested. Prospective visitors would cross the narrow and unpaved mountain pass of the Sierra de Yamasá on buses, and controversially for many, hand over their national ID card numbers and signatures as a condition of entry to the corporation’s mining installations. These guided tours covered selected parts of the gold mine’s vast premises and were meant to turn “la mina,” the physical manifestation of the massive corporate entity that is Barrick Gold, into a benign and familiar object of experience (Golub 2014).

Since the summer of 2020, community residents in Monte Plata have been engaged in robust opposition to the corporation’s plan to place a tailing dam, which would hold muddy sludge laced with chemicals like cyanide and sulfur in perpetuity, in their area. They interpreted the “official” tours as a tactic to sow uncertainty about the impact of the use of cyanide and other heavy metals in the gold mining process (Rodriguez Grullón 2012). During the visits, some residents complained that they could not visit the areas surrounding the Pueblo Viejo mine, where more than 450 families struggle to survive the effects of heavy metal pollution. For more than a decade, these families have protested over the lack of clean water and the rise of pollution-related health complications in order to push the Dominican state to relocate them to a more livable space.

After the visits, the mine’s social responsibility personnel filmed selected individuals, who attested to the lack of pollution at the installations, much to the shock and chagrin of their neighbors across the mountains who saw the videos later. In response, those in opposition to the new tailing dam project launched a counter-campaign of alternative tours, precisely centering the communities avoided in the “official” tour. Stepping out of the curated experience in the heavily securitized installations, these alternative visits offered the perspectives of residents experiencing various illnesses they linked to toxic pollution. Following these visits, activists opposing the second tailing dam circulated video testimonies to challenge the mine’s own version via WhatsApp, Facebook, and other forms of social media. By employing a similar pattern of inquiry, experience, representation, and digital circulation, they exerted agency from below, challenging official narratives that frame mining as technoscientific progress and showing what the mine’s waste actually does.

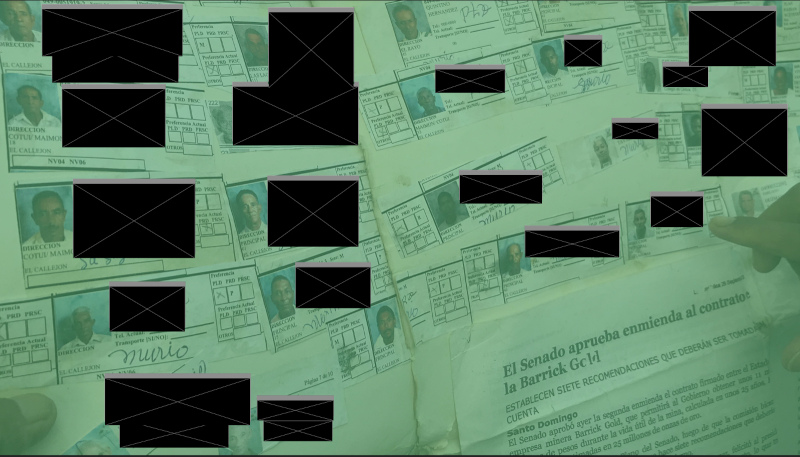

A community member representing communities living around the Pueblo Viejo mine holds images of those who have passed away from health complications over the past 5 years. Photo by author.

Entangled Webs of Corporate and State Chemical Violence

As April continued, Barrick Gold resorted to community meetings and dialogues to create community consent for its project ahead of its Annual General Meeting on May 5th, 2021. On April 29th, 2021, Yamasá residents blocked the entrance to a site where the mine intended to hold one such community meeting. The Dominican military, SWAT tactical units, and police forces used pepper spray, smoke bombs, and bullets to clear defiant community members who held their ground, in an effort to prevent the meeting. I filmed this instance of violence, as my primary informants and I ran from tear gas, gas bombs, and live bullets after more than 7 months of peaceful protest. Still reeling from the events, I edited some of the footage into a short video highlighting what happened that day. Since then, suspicion, anger, and fear have created a climate of collective stress and anxiety among friends and neighbors living in the Yamasá mountains.

States and corporations deploy violence when technoscientific uncertainty about toxic harm fails to generate consent, or at least, the perception of it. Without such consent, in the form of social licenses to operate, prospective mining projects around the world would not be approved. While specific to the patterns of island extractivism in the Caribbean, this story could have occurred in any of the more than 4,000 mining projects that Canadian-based corporations hold all over the world, including its 26 projects across the Caribbean and Central America. This brings me to the questions that I posed earlier: what is anthropologists’ role in creating new ways to examine the links between mining, pollution, technoscientific design flaws, lack of corporate accountability, and individual environmental agency from below? What other, perhaps better, questions can we ask when the role of the capital derived from corporate toxicity becomes evident in our own lives beyond the field?

As news about the April 29th crackdown circulated among the Dominican diaspora in New York, seeking the alterlife of cyanide at Barrick Gold’s Pueblo Viejo mine necessarily required a move beyond the scale of the pore, or the site that congeals the complex relationship between human bodies and natural landscapes experiencing harm. “Art-washing” emerged as a perfect metaphor to reveal how state and corporate chemical violence alchemized into forms of sociocultural capital back “home.”

Art-Washing the Profits of Corporate Chemical Harm

In May of 2021, the Decolonize this Place and Strike MoMa collectives revealed that Gustavo Cisneros, one of Barrick’s independent directors and a multi-millionaire media mogul, is connected to the Museum of Modern Art through his wife’s extensive art collection and philanthropy work. Patricia Phelps de Cisneros had amassed a private collection of Latin American art and created a research institute at the MoMa in 2016. This revelation ignited a transnational campaign against Barrick’s expansion, highlighting a phenomenon that Macarena Gomez-Barris calls “art-washing.” The term refers to the moral and financial legitimization of funds obtained through extractive industries by bringing them into the art world and other reputable sources of prestige, power, and respectability.

Forensic Architecture’s 2019 film Triple Chaser, in which a computer was trained to identify Sarafiland’s tear gas canisters through machine learning. Photo by Eileen Kinsella, featured here.

The 2019 controversy surrounding the Whitney Museum of American Art Biennial is yet another example of art-washing of profits from a nexus of corporate pollution, state violence, and technoscientific dissimulation. Warren Kanders, the founder and CEO of Safariland (a tear-gas manufacturer), is the ex-Vice Chair of the Whitney Museum of American Art’s board. Kanders’ company produced the tear-gas[1] used in dozens of sites across the globe, where state forces have used violent means to suppress anti-colonial and anti-racist action. As Forensic Architecture’s 2019 short film shows, New York City, Ferguson, the U.S.-Mexico borderlands, Istanbul, and the Gaza Strip are interlinked through Safariland’s chemical weapon: tear gas. The profits from activities that pollute must be circulated and “washed” to gain new value, just as billions of pounds of former mountains must be “washed” in a vat of chemicals so that rock and mineral separate. Yet in both processes, an undeniable toxic trace remains.

“Washing” here comes to life not as a cleansing and purifying technique, but rather as financial and social labor that stains the very pores of those who perform it, and benefit from it, with the toxic stench of racial capitalism. Tracing that stench in our own lives is neither easy nor comfortable.

Conclusion: Becoming Toxic Together?

The art-washing of toxicity-derived profits tie spaces of extractivism, social protest, and anti-colonial uprising to each other. These ties compel us to seek the resonances of extractivism beyond the immediate, beyond the environmentally-harmed body or the destroyed landscape. The “alterlife” of profits gained through the manufacturing and use of cyanide, in the case of Cisneros, and tear gas, in the case of Kanders, leads us to the most prestigious art museums and universities of the world. It leads to us. Before doing the research that I do now and before knowing what I know now, I was a volunteer at one of the Cisneros families’ social responsibility projects in the Dominican Republic for three-month-long stints. Kanders is an alumnus and a member of the advisory council for the Institute for Environment and Society at Brown University, my undergraduate institution.[2] While seemingly incidental, these connections implicate me and give further urgency to the questions I set out at the beginning of this piece.

The flow of corporate capital derived from pollution, harm, and technoscientific denial accompanying extraction inextricably intertwines the Museum, the University, the Private Collection and other spaces of colonial and metropolitan prestige and power where anthropologists are at home with the bodies and plight of the ailing residents of Cotui and the asphyxiated children of the Gaza Strip. Places, not at all near in proximity, and bodies, at first glance not at all in relation, become together, but not always through the forms of contact we hypothesize and expect. All these bodies, institutions, and forms of knowledge are always already in circulation, already transforming each other. This invisibilized enmeshment too is an element of extractivism that arrives knocking at the anthropologist’s door, as it did for me even before I began my research.

Combatting our complicity requires deeper self-reflection and ethical action, including saying no to profits, fellowships, and grants derived through art- or academic-washing. Another aspect of ethical responsibility also lies in thinking speculatively and expansively about the possibilities of living altered nonetheless. By way of conclusion, to arrive at a way to think through our toxic “becomings,” I suggest drawing on the lessons of scholars like King (and those she cites such as Sylvia Wynter, Hortense Spillers, and Saidiya Hartman) and center the cosmologies, refusals, and social practices of the beings who experienced racial capitalism’s circulations, washings, and alchemies first.

References

Ferrie & Sabados. (2021). “Canadian Professor Critical Mining Report Tanked by Dominican government.” Canada’s National Observer. Accessed on June 22nd, 2021. https://www.nationalobserver.com/2021/06/16/news/canadian-professors-critical-mining-report-tanked-dominican-republic?fbclid=IwAR3CU2Rl9_VIYQaN1xGHIOfmLjX7vP8Sxw64IEeCX2dt1wep9trVq6KVlJo

Golub, Alex. (2014). Leviathans at the Gold Mine. Durham, NC: Duke University Press

Grullón, V. A. R. (2012). Tras el oro de Pueblo Viejo: del colonialismo al neoliberalismo: un análisis crítico del mayor proyecto minero dominicano. Publicaciones de la Academia de Ciencias de la República Dominicana.

King, T. L. (2019). The Black shoals: Offshore formations of Black and Native studies. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Liboiron, M., Tironi, M., & Calvillo, N. (2018). “Toxic politics: Acting in a permanently polluted world.” Social studies of science, 48(3), 331-349.

Murphy, M. (2017). “Alterlife and decolonial chemical relations.” Cultural Anthropology, 32(4), 494-503.

Robinson, C. J. (2020). Black Marxism, Revised and Updated Third Edition: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. Chapel Hill: UNC Press Books.

Footnotes

[1] “Tear gas is a chemical weapon: a mist of toxic particles that inflames mucus membranes and triggers pain receptors wherever it touches. The skin burns, the eyes water, the throat swells, it’s almost impossible to breathe.” For more, see: https://www.artforum.com/slant/a-statement-from-hannah-black-ciaran-finlayson-and-tobi-haslett-on-warren-kanders-and-the-2019-whitney-biennial-80328

[2] Students protested Kanders’ ties to the university in 2019.