Surfing’s roots are in long-standing cultures in the Pacific Islands, South America, and West Africa. After wave-riding was banned by European Missionaries who deemed it leisurely and “savage,” surfing’s contemporary “revitalisation” took place in Hawaii where it became a notable phenomenon of the 20th century. Nowadays, surfing represents a subculture around an “alternative” sport, a lifestyle, and an art with profound personal and lifestyle implications (Ford & Brown, 2006). Likewise, in India, particularly in the fishing village Kodi Bengre, surfing means much more than simply sliding along a wave. This qualitative study captures how the Shaka Surf Club shapes perceptions of well-being and mental health in surfers and surrounding community members in Kodi Bengre.

While preparing for my journey to Manipal, India, where I would spend a semester studying, I stumbled upon the website of the Shaka Surf Club. As an avid surfer myself, I was instantly drawn to stay at the surf club. During my six-month stay in Manipal, my daily routine led me to Shaka, where I spent hours in the ocean indulging in my great passion. Yet, due to the friendships created and community found, Shaka was more than just a surf club to me. As a white female European, I felt a sense of belonging in a country once so foreign.

Two men walking along the street in front of the Shaka house (Credit: Laura Werle)

In the 1970s, Jack Hebner, known as “Swami” and from Jacksonville, USA, brought surfing to India by founding a surf school in Mangalore, India, where he taught internationals and locals how to surf. Surfing in India can be seen as a neo-colonial, “Western” sport because it did not begin in India, even though records of Indigenous surfing exist (World Surf League, 2022). Yet, the Indian-led development of surfing has the potential to create a sustainable local surf culture. Surfing in India is an inter-caste phenomenon and encourages interaction, communication, and friendships between people from different backgrounds. A sense of community is fostered by being in the water as brothers, sisters, and friends (Quicksilver India, 2013).

While surfing may foster a sense of unity across caste lines, it also reflects broader gender inequalities. Surfing is a sport shaped by masculine gender norms (Comley, 2016) with its history marked by sexism and discrimination (Ford & Brown, 2006). Gendered difficulties in accessing surfing also apply to Indian surfers. For example, for girls and women it is considered a problem that surfing darkens skin colour, as dark skin is seen as less beautiful.

Surfing also has implications for and around the environment. For instance, plastic pollution is a critical environmental crisis, driven by a surge in waste, lack of recycling options, and poor waste management, impacting rivers, oceans, and terrestrial ecosystems (Pathak, 2020). Surfing brings attention to India’s ecological systems, with the surfing community emerging as a national voice for the protection of coastlines and the fight against plastic infiltration (Miller & Fechser, 2015).

Local surfers have explored deep connections with the ocean in what some have described as spiritual experiences (Shamaran, 2020). These connections cultivate compassion towards living beings and allow for self-reflection and living in the present moment (Taylor, 2010). Some studies have been exploring the therapeutic potential of surfing on the well-being and mental health of individuals, such as reduced anger, depression, and stress, as well as increased sleep quality (Podavkova & Doleis, 2022). The research described in this post similarly aimed to provide insights to improve low-cost mental health support and interventions in coastal areas and fisher communities, which often have fewer mental health services and resources yet high rates of depression, anxiety, and suicide risk.

Research at the Shaka Surf Club

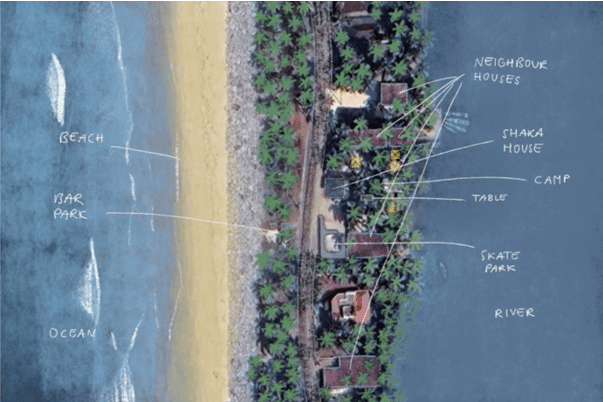

This study was conducted at the Shaka Surf Club, which is located in Kodi Bengre, a small fishing village home to 8,500 people on the coast of the state of Karnataka in southwestern India. Situated between the Arabian Sea and the backwaters of Suvarna River, water surrounds the village on both sides. The Shaka Surf Club is named after the Hawaiian gesture of “hang loose” or “take it easy,” reflecting the club’s philosophy of embracing freedom in the waves, spreading good vibes, and learning to go with the flow. It was founded in 2007 by Ishita Malaviya and Tushar Pathiyan, who originate from Mumbai and learned the basics of surfing from “Swami” at Mantra Surf Club. They continued to teach themselves to surf while studying at Manipal Academy of Higher Education and began to give lessons to fellow students. Initially mostly foreigners came to surf, but now also local children and adults from nearby cities learn to surf (Khanna, 2015). The surf structure is community-based, and constitutes an important place where community members can come together. Local children receive free surf and skate lessons, and surrounding community members are employed to provide various services. Shaka represents a community within a community due to its opportunities for people of different backgrounds to interact and engage in activities like surfing and skating.

Map showing a section of Kodi Bengre and the location of Shaka Surf Club (Credit: Laura Werle)

This study uses a phenomenological approach, which highlights the lived experiences of participants to capture perceptions and attitudes on mental health and well-being. I conducted 16 interviews with community members and surfers who have experience in supporting or using the Shaka Surf Club. Moreover, I used an autoethnographic approach, as I spent six months at the Shaka Surf Club surfing, skating, and building relationships. Hence, I explore and share the reflections I made during my personal journey at Shaka, where I immersed myself in the waves and the vibrant community present.

Findings: Improving Mental Health

Surfing led to an overall positive influence on mental health and well-being, with a noted profound impact on intrapersonal skills, personal growth, and sociability through surfing at Shaka Surf Club. Surfing there goes beyond catching waves, and Shaka’s role surpasses that of a surf school. Participants noted a familial atmosphere within Shaka, which forges a sense of belonging. Communication between surrounding community members is fostered, with a notable emphasis on encouraging inter-gender dialogue. At Shaka, individuals of all genders come together not only to discuss work-related tasks but also to engage freely in conversations with one another. Shaka Surf Club’s impact on community interactions is further facilitated by the physical spaces it provides, serving as a central gathering point.

“We all sit together, me and all, everyone is there of different ages, different groups. Yeah. We all get together here. I find happiness as I look at people, [when] I come to Shaka. I speak, I interact.” [Neighbour, 66-year-old woman, responsible for cooking lunch for Shaka]

Neighbour boy/surfer walking towards the skate park (Credit: Laura Werle)

Furthermore, Shaka serves as a source of stable employment, financial security, and improved working conditions for five neighbouring families in Kodi Bengre. Notably, the stress experienced by participants formerly employed within the fishing sector from workload, job insecurity, and poor work environment emerged as a crucial factor influencing their mental health. Take, for instance, the journey of the 27-year-old campsite manager, formerly a fisherman on a trolling boat, whose mental health suffered under the hardships of the occupation. At the age of 14, he dropped out of school to support his family amid his father’s alcoholism. His life took a positive turn upon discovering surfing and starting a position as a surf instructor at Shaka. Today, not only does he provide for his family, who reside an hour north of Kodi Bengre, but he also experiences newfound stability in his mental health.

The perceptions of surfing underscore that the interplay with the ocean has a significant influence on individuals’ mental well-being. Participants highlight how surfing fosters mindfulness, creating a strong connection to the present moment, that extends to their daily lives. The development from a mental state of stress and apprehension to one of mental peace and confidence underlines the therapeutic dimension of surfing and its positive influence on mental health issues.

“Surfing helped me with my mental health. When I get stressed or something, I go take my board and go to the ocean. And just chill in the water. When I am in the water, if I catch a wave then I don’t think [about] anything. I’ll just be happy that I got the wave.” [Surf instructor, 24-year-old man, born in a fishing village located one hour from Kodi Bengre]

Surfing and other activities at Shaka Surf Club have impacted participants’ human-nature connectedness. Initial fears of the water transformed into appreciation for the ocean’s energies. Surfing extends upon preexisting connections to nature stemming from fishing-related experiences. Here, fishing represents a cultural connection with the ocean, incorporating knowledge about the natural environment and the sea’s capabilities. Yet, participants express that surfing unveils a profound way to forge intimate connection with the ocean and nature that extends beyond previous boundaries, enabling joy, harmony, and an immersive communion with the natural world. This connection to nature raises awareness for the natural environment and creates passion towards protecting the ocean.

“You be humble in the process, yeah. You respect the surroundings. You know you respect the natural elements that are there around you. If you respect nature, you will get respect back from nature. You’ll get love and care back from nature. You’ll get fed by nature, you know, that’s the ultimate goal.” [Surfer and operations manager, 35-year-old man, from Mumbai, India]

View of the backwaters of Suvarna river from Shaka (Credit: Laura Werle)

Gender-related disparities in surfing access and participation emerge due to a range of barriers, including community acceptance, limited role models, and norms. These barriers particularly affect the involvement of local women in surfing. While there are male surfers from the village of Kodi Bengre, local female participation in the water remains limited. This gender disparity in participation not only highlights the inequality in access to surfing but also underscores the direct repercussion on their mental well-being, as they miss out on potential benefits that surfing offers.

In sum, the intricate interplay of various factors on intrapersonal, interpersonal, social, environmental, and community levels unveils the transformative effects of Shaka Surf Club extending to both individuals and the community. However, the extent to which individuals’ mental health and well-being is shaped depends upon their level of participation in activities and the space of Shaka Surf Club, as well as gender distinctions.

References

Comley, C. (2016). “We have to establish our territory”: how women surfers ‘carve out’ gendered spaces within surfing. Sport in Society, 19(8-9), 1289-1298.

Ford, N.J. & Brown, D. (2006). Surfing and Social Theory. Experience, Embodiment and Narrative of the Dream Glide. Routledge

Khanna, J. M. (2015, 1 Sept). At home at sea: India’s surfing revolution. Traveller. https://www.cntraveller.in/story/home-sea-india-s-surfing-revolution/

Miller, C. & Fechser, F. (2015). Surfing into Samadhi: Rediscovering the elements in India’s Coastal Villages.

Pathak, G. (2023). ‘Plastic Pollution’ and Plastics as Pollution in Mumbai, India. Ethnos, 88(1), 167–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.2020.1839116

Podavkova, T. & Dolejs, M. (2022). Surf Therapy—Qualitative Analysis: Organization and Structure of Surf Programs and Requirements, Demands and Expectations of Personal Staff. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 2299. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042299

Quicksilver India. (2013). A Rising Tide – The India Surf Story. [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xS1FrNtHzzk

Shamaran, A. (2020). The Secret Surf Culture of India [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NBqEQ8x6fxE

Taylor, B. (2010). Dark Green Religion: Nature Spirituality and Planetary Future. University of California Press.

Tiwari, R. (2010, November 18). Caste System and Social Stratification in India. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2067936

World Surf Leage (2022). Soul & Surf Kerala. Brilliant Corners. https://www.worldsurfleague.com/watch/447203/wsl-studios-brilliant-corners-india