There are Birds on the Wire

In Mexican slang, “hay pájaros en el alambre” (there are birds on the wire), is an expression used to imply that a private conversation is at risk of being intentionally overheard. Birds on the wire can mean anything from one’s auntie overhearing a conversation from the other room, to a phone being wiretapped at long range by a state agency. In everyday parlance, this phrase does a lot of work to signal a broader awareness and cultural acceptance of surveillance. If, in conversation, someone is reminded of the birds on the wire, they are expected to beware—not for the birds to go away. Perhaps the statement produces a chilling effect of sorts, rather than an expectation of privacy.

In this post, I want to show that this very particular instance of everyday surveillance in Mexico is telling of the cultural backdrop in which it occurs. The ways that surveillance technology is acquired and deployed, often in the name of security, contributes to the establishment of a culture where surveillance is normalized. However, this move is not devoid of tensions, as the high social costs of surveillance efforts become visible and sectors of civil society begin to challenge the emerging sociotechnical status quo. I also point to the ways that these developments have made an impact beyond Mexican borders, in the global surveillance technology market, and among global advocacy movements organizing around privacy rights.

My broader research is about the ways that countries like Mexico, with relatively high acquisition power and little surveillance oversight, become both key funders and early adopters of some of the most insidious surveillance technologies used worldwide today. Ethnography is well suited to explore this pressing question: How is it that surveillance becomes normalized in everyday life, co-creating the necessary social and political conditions that further the provisioning and deployment of major surveillance technologies—those which would have otherwise raised eyebrows? What does it entail to challenge surveillance in a place where surveillance is expected?

Surveillance studies scholar David Murakami Wood reminds us that “while surveillance is involved with processes of globalization, it is also not necessarily the same ‘surveillance society’ that one sees in different places and at different scales” (2009). Mexico’s use of surveillance technologies—both those imported from global markets and those locally created—is a local instance of a global phenomenon, unique in its own way while further contributing to a market that extends beyond Mexican borders. If surveillance can be understood through the theoretical lenses of ‘society’ in sociology and ‘sociotechnical systems’ in STS, Mexico’s birds-on-the-wire culture can lend itself to anthropological study.

Figure 1. A biometric check-in at the worker entrance of a luxury gated community in Mexico City. The sign instructs, “If the system does not open for you, erase your photograph and take it again. Make sure your photograph complies with the following: Your face must cover 90% of the camera. Light background without objects. Uncovered face, without glasses. The photo should be front-facing. No shoulders nor full body. Good lighting without shadows.”

Depictions of surveillance in publicity and popular media seem to take part in an aesthetic. Biometric technology vendors demonstrate their products through images of facial polygons measured and calculated with bright lines, followed by images of neon-print-on-black databases that seemingly animate the digital finding of “accurate” matches. In reality, removed from the public relations machine, biometric surveillance might look like the worker checkpoint pictured above. This is a biometric identification station located at the worker entrance of a luxury gated community in Mexico City. Delivery drivers, cleaners, and other workers line up in front of this station and remove their face coverings to be photographed as they request access. This particular gated complex does not bother to display the usual aviso de privacidad, the privacy notice required by Mexican law,[1] perhaps assuming that workers were unlikely to engage in data refusal, or, in other words, to reject the collection of their data.

The actual residents of this and other luxury gated communities have separate entrances, where biometric identification is deployed in very different ways from the ones used to track workers. Instead of having to uncover their face and smile for a camera, residents merely press a fingertip onto a scanner. However, in this case, the technology vendor’s website also advertises another use of facial recognition: “VIP guests” can have preferential access enabled through facial recognition, “without the need to interact with security guards.”

Legacies of State Surveillance

Alongside its use in everyday parlance, birds on the wire alludes to the overarching surveillance state in Mexico; it is in such a context that government officials would find it permissible to acquire technology to surveil dissidents, as they have done throughout the twentieth century. Historians Sergio Aguayo Quezada (2001) and Cesar Valdez Chavez have written the most comprehensive account of 20th-century Mexican surveillance culture in its institutionalized form, recounting the bureaucratic origins of the Departamento Confidencial de la Secretaría de Gobernación (Confidential Department of the Secretary of Interior), and then the Dirección Federal de Seguridad (Federal Security Directorate), Mexico’s secret police. Aguayo Quezada surfaces and analyzes information regarding the specific tactics and artifacts historically used to surveil dissidents. By 1965, wiretapping had evolved into an operation involving at least 117 strategically tapped telephones in Mexico City. The government had also inspected private letters and telegrams with cooperation between intelligence services and the Mexican Postal Service, the Mexican Telegraph Company, and the Secretary of Communications and Transportation. There were also cameras placed outside of the Soviet embassy and other locations of state interest.

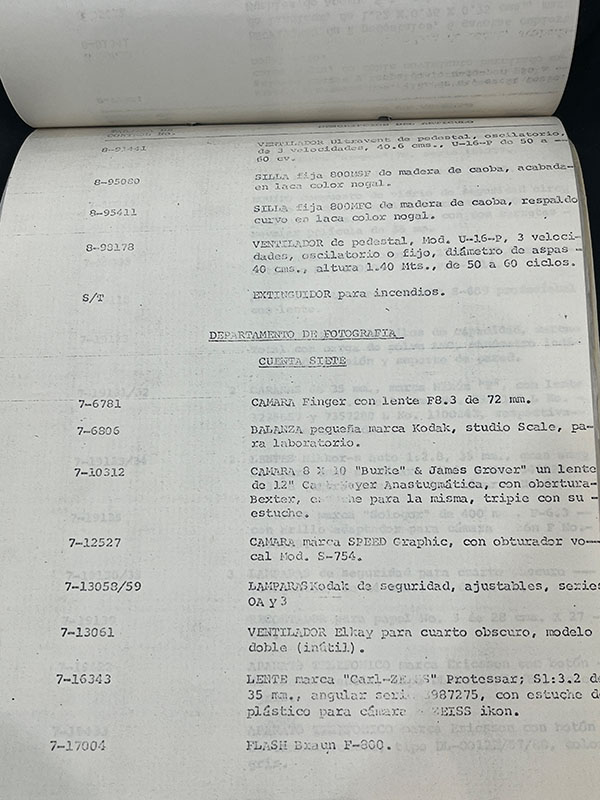

Figure 2. Inventory listing the cameras owned by the photography department of the Mexican Federal Security Directorate. [Archival source]

A central justification for the birds-on-the-wire approach of many aspects of Mexican life—including residential management—is the so-called “security crisis” (Benítez Manaut, 2009). The vendor of biometric identification technology for the luxury community described above uses the rhetoric of surveillance for security as a selling point to potential future residents. The home page of the vendor’s website reads, “Are you tired of robbery and crimes at your residence? Our system does not tell you how you got robbed, it prevents it!” Their solution, however, comes at a high price for privacy, as it operates without transparency regarding the custody of the personal identifiable information they gather. This case of the gated community in Mexico serves as a local materialization of the globally experienced tensions between security and privacy rights (Landau 2010; Monahan 2010; Zureik and Salter 2013).

Security for Whom?

Through my fieldwork I’ve found that these tensions are now erupting at the center of Mexico’s birds-on-the-wire culture. On the one hand, one can see the signs of a successful private security technology industry through every CCTV warning sign displayed outside residences and shops. The deployment of cameras is so widespread that, in a press conference in 2019, the head of Mexico City’s Public Innovation Digital Agency announced a program that would plug businesses’ private video surveillance directly into the Command and Control Center that oversees surveillance in the city. In the same press conference, then Mexico City mayor (and now 2024 President-elect) Claudia Sheinbaum announced plans to renew and augment 18,500 video surveillance cameras throughout the city, equipping them with updated capabilities (Gobierno de la Ciudad de México 2019).

Figure 3. A sign outside a surveillance camera shop in Mexico City. The shop, with desks where vendors show pamphlets and information to potential customers, is located on a busy road. Above the vendors, there is a big display of the live feed of the street outside the shop, captured by different cameras.

Figure 4. Sign outside a quinceañera dress shop in Mexico City, calling attention to their CCTV security system.

On the other hand, increasing surveillance does not go uncontested. The madres buscadoras, organized families of forced disappearance victims, have long denounced that security camera footage is rarely used for their investigations, leading them to acquire their own equipment such as drones to find clandestine graves (Osorio, 2024). In 2021, global technology outlet Rest of World published an investigation by journalist Madeleine Wattenbager titled “Where surveillance cameras work, but the justice system doesn’t,” recounting stories of how cameras had failed to advance justice for victims of crime in Mexico City.

Doubts around surveillance effectiveness further add to the social cost of surveillance technologies in a context where personal data are routinely leaked or stolen and sold online. In 2016, political party Movimiento Ciudadano uploaded the registered voters database, leaving it unprotected (Expansión, 2016). In 2021 a hacker offered the user databases of two banks and Mexico’s Social Benefits Institute for sale on a forum, a month after he also offered the data of 60 million users of telecommunications company Telcel (La Silla Rota, 2021). Surveillance and other mass personal data collection efforts in Mexico have to contend with this reality: data leaks are not abstract events in risk assessments, but rather concrete privacy rights violations that occur with distressing frequency.

The national context amplifies the tension already seen in everyday life. The federal government’s contemporary technology acquisitions are at the crux of the surveillance-for-security ideology. As Mexico deals with a human rights crisis where over 95% of crimes remain uninvestigated (México Evalúa, 2022), the promise of technological silver bullets for reducing violence finds fertile ground and willing constituents, creating the political will and funding for some of the most insidious projects. Most recently, Mexico’s so-called war on drugs “expanded the Army’s budget, size, and stock of equipment” (Grayson, 2013: 68). Since 2006, over $3 billion USD has been appropriated in the United States to support Mexico’s fight against crime, used to purchase military aircraft, surveillance software, and related equipment (Council on Foreign Relations, 2022).

What is notable about this expenditure, made in the name of national security in Mexico, is that its effects are also felt by dissidents around the world. In 2011, the Mexican Secretary of Defense approved a contract to import Israeli cyberarms firm NSO Group’s now infamous Pegasus malware. Well before global awareness of Pegasus, the Mexican government became the primary customer of the NSO Group (Kitroeff and Bergman, 2023). This initial contract provided a funding runway “which more or less launched NSO as a viable company” (Richard and Rigaud, 2023).

The question raised by the micro and the macro is: Who is the intended beneficiary of this technology-enabled security? If victims of the worst crimes in Mexico don’t see the benefits of surveillance, and the social costs rise with every data leak, then who do these technologies serve? As things stand, it would seem easier to answer who is not served. CCTV cameras do not serve the mothers of victims of forced disappearance nor other victims of crime. Similarly, Pegasus does not promote the best interests of one of the most endangered groups: journalists practicing in the “deadliest country for journalism” in the Western Hemisphere (Committee to Protect Journalists, 2023).

Resistance in the Face of Surveillance Harms

Pegasus and other forms of federally-contracted surveillance technology are part of the continuum of violence perpetrated against journalists; revelations in 2020 confirmed that Israeli surveillance malware Pegasus had been deployed against Cecilio Pineda, a Guerrero journalist who was ultimately murdered in 2017 (Casals Martínez and Sánchez Pardos 2022). Since 2016, there has been ample evidence of the use of Pegasus against journalists, public health experts, and activists in Mexico—so much so that the 2016 revelations constitute Mexico’s “Snowden moment,” an inflection point where media and politicians denounced the disproportionate and illegal use of surveillance.

Following these revelations, birds-on-the-wire surveillance culture has remained the backdrop for public discourse, creating advocacy challenges for civil society campaigning against surveillance. What does it entail to challenge surveillance in a place where surveillance is expected? In an interview, an officer working for the Mexican chapter of freedom of the press organization Article 19, shared to me his ideas about both the windows of opportunity and the difficulties in advocating against surveillance:

I can tell you about the majority of people, if you asked them, do you think the government is spying illegally on journalists? The majority of people would say yes. And that is good in a way because we don’t have to revert that perception, which would have been worse, right? It would have been worse for people to say, ‘No, I trust the government entirely when it says it no longer surveils us.’ But at the same time it’s been frustrating that normalization leads to the tacit acceptance of that behavior, so our revelations of journalist surveillance didn’t make a bigger impact.

The movement against Pegasus in Mexico meant a deviation from the narrative of normalized surveillance in the name of security regardless of any social costs. When some of the first Pegasus remote code execution cases worldwide were documented in Mexico, activists there succeeded in creating a spotlight through international media and strategic litigation, highlighting the ways that the deployment had been illegal, unwarranted, and harmful. Their advocacy turned out to be key to different sociotechnical impacts felt worldwide: nowadays, Apple will notify users if they have been targeted with Pegasus, and this cyberarm in particular has been added to the trade restriction list in the United States.

Some of these victories can also be seen in everyday life. It is true that, during my fieldwork, I encountered surveillance shops, trade shows, and marketplaces for spyware. My face was filmed by drivers every time I got on an interstate bus, and my fingerprints were taken as I arrived to interview higher profile individuals. My full voter registration number is on many security logs across the country, noted down by private security guards as a condition of entrance to private buildings. However, in that same context of everyday surveillance, I also saw workshops full of activists and journalists who wanted to learn how to better protect their data and their sources. I saw a high school class learning about data protection and the right to privacy. I saw the press conferences and events where undue surveillance was denounced.

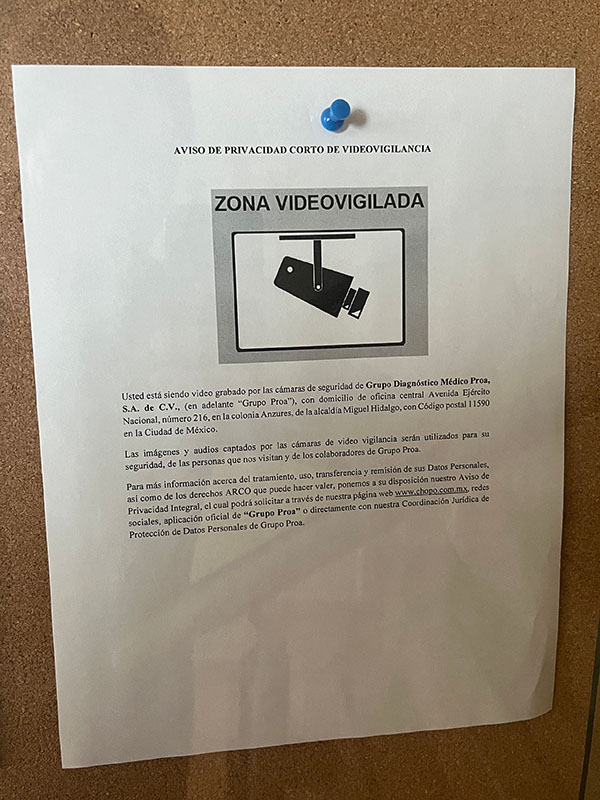

Perhaps most importantly, most places I went, even if not at the biometrics station for workers in the luxury gated community, I saw privacy notices. They always came in the shape of boilerplate text print-outs on display at the entrances of different establishments, meant to comply with the personal data protection law approved in 2010. An official working for the National Institute of Access to Information and Data Protection in Mexico told me in an interview that those privacy notices alone were a privacy success in Mexico, “a measure that restores the framework of personal data protection not just for one individual but for all the people who have to deal with an entity that manages their personal data.”

Figure 5. Privacy and video surveillance notice at a medical laboratory in Mexico City. The privacy notice text details the personal data recorded at the lab. The video surveillance notice vaguely mentions that the data “will be used for your safety, of those who visit us and of Grupo Proa collaborators.”

Perhaps we can say that it is precisely in the context of the most pervasive everyday surveillance that privacy rights become more precious—that something about a birds-on-the-wire culture highlights the importance of the right to dissent in the face of boundless data collection. The heterogeneous surveillance structures across different sites in Mexico serve as a cultural backdrop to public and private security expenditure, and thus to the funding of surveillance technologies worldwide. It is precisely because of that, however, that ethnographic fieldwork and counterveillance (Welch 2011) can be central to exploring the ways that birds-on-the-wire culture serves as a backdrop for its resistance.

If the post-9/11, post-Snowden, post-Pegasus experience of surveillance in Mexico can tell us anything, it’s that birds-on-the-wire discourse is a telling story of how surveillance becomes normalized, but also of the ways privacy rights activism has still been able to garner success in the face of a phenomenon with cultural acceptance. This is a lesson for the global movement for privacy and necessary and proportionate surveillance: even in places where surveillance has long been the norm, organized advocacy can build momentum not to question the interlocutors on the wire, but to imagine a world where one day the birds might fly away.

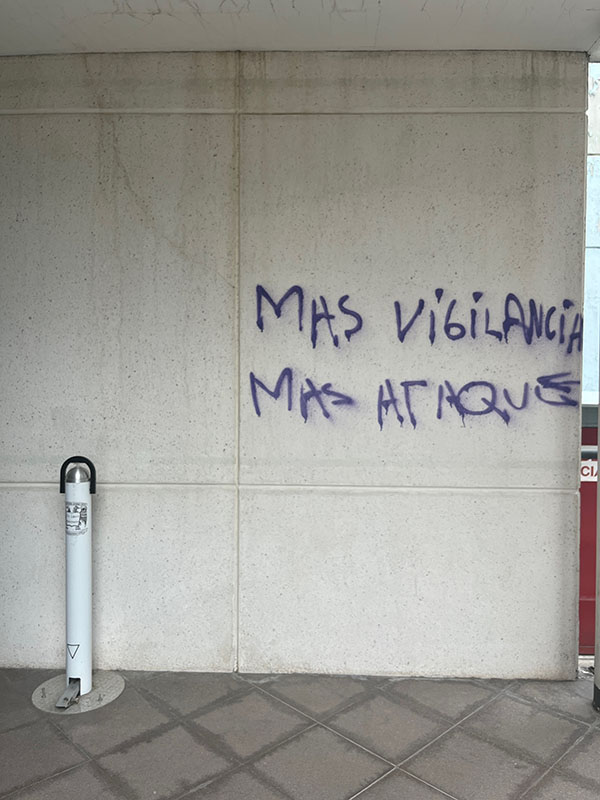

Figure 6. Graffiti at the School of Political and Social Sciences of the National University of Mexico which says, “More surveillance, more attacks.”

Notes

[1] Mexico’s Personal Data Protection Law of 2010 requires bound entities, namely those managing personal data, to visibly display a privacy notice in their premises. Among other things, the notice must include the details about the types of data that will be collected, who will have access to it, and with what intent.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Alex Rewegan, Chris Featherman, and Jessica Olivares for their insights and editing.

This post was curated by Contributing Editor Alex Rewegan.

References

Aguayo, Sergio. 2021. La Charola: Una Historia de Los Servicios de Inteligencia En México. Grijalbo.

Committee to Protect Journalists. 2023. “In 10 days, 8 Mexican journalists abducted or shot at in 4 separate incidents,” 4 December. https://cpj.org/2023/12/in-10-days-8-mexican-journalists-abducted-or-shot-at-in-4-separate-incidents/

Benítez Manaut, Raúl. 2009. “La crisis de seguridad en México.” Nueva Sociedad 220:173-189.

Council on Foreign Relations. 2022. Mexico’s Long War: Drugs, Crime, and the Cartels. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/mexicos-long-war-drugs-crime-and-cartels (Accessed 24 April 2024).

Expansión. 2016. “Movimiento Ciudadano admite que subió los listados nominales a Amazon” [Movimiento Ciudadano admits they uploaded the voter registration database to Amazon], Expansión, 27 April. https://expansion.mx/politica/2016/04/27/movimiento-ciudadano-admite-que-subieron-el-padron-electoral-a-amazon.

Gobierno de la Ciudad de México. 2019. “Visión 360º” [360º vision], Centro de Comando, Control, Cómputo, Comunicaciones y Contacto Ciudadano de la Ciudad de México, June 3. https://c5.cdmx.gob.mx/storage/app/media/Boletin/Vision-360.pdf.

Grayson, George. 2013. “The Impact of President Felipe Calderón’s War on Drugs on the Armed Forces: The Prospects for Mexico’s “Militarization” and Bilateral Relations.” Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep11780

Kitroeff, Natalie, and Bergman, Ronan. 2023. “How Mexico Became the Biggest User of the World’s Most Notorious Spy Tool.” The New York Times, 18 April. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/18/world/americas/pegasus-spyware-mexico.html.

Landau, Susan. 2020. Surveillance or Security? Risks Posed by Wiretapping Technologies. MIT Press.

Monahan, Torin. 2010. Surveillance in the Time of Insecurity. Rutgers University Press.

Osorio, José Luis. 2024. “In Mexico, mothers of the missing turn to drones to look for unmarked graves.” Reuters, 26 January. https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/mexico-mothers-missing-turn-drones-look-unmarked-graves-2024-01-26/.

Richaud, Laurent, and Rigaud, Sandrine. 2023. Pegasus: How a Spy in Your Pocket Threatens the End of Privacy, Dignity, and Democracy. Henry Holt and Company.

Valdez Chávez, César. 2021. Enemigos fueron todos: Vigilancia y persecución política en el México posrevolucionario (1924-1946). Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Bonilla Artigas Editores.

Welch, Michael. 2011. “Counterveillance: How Foucault and the Groupe d’Information sur les Prisons reversed the optics.” Theoretical Criminology 15(3): 301-313.

Wood, David Murakami. “The ‘Surveillance Society’: Questions of History, Place and Culture.” European Journal of Criminology 6(2):179–94.

Zureik, Elia, and Mark B. Salter. 2023. “Global Surveillance and Policing: Borders, Security, Identity–Introduction.” Global Surveillance and Policing 13-22. Willan Publishing.