Data for Discrimination

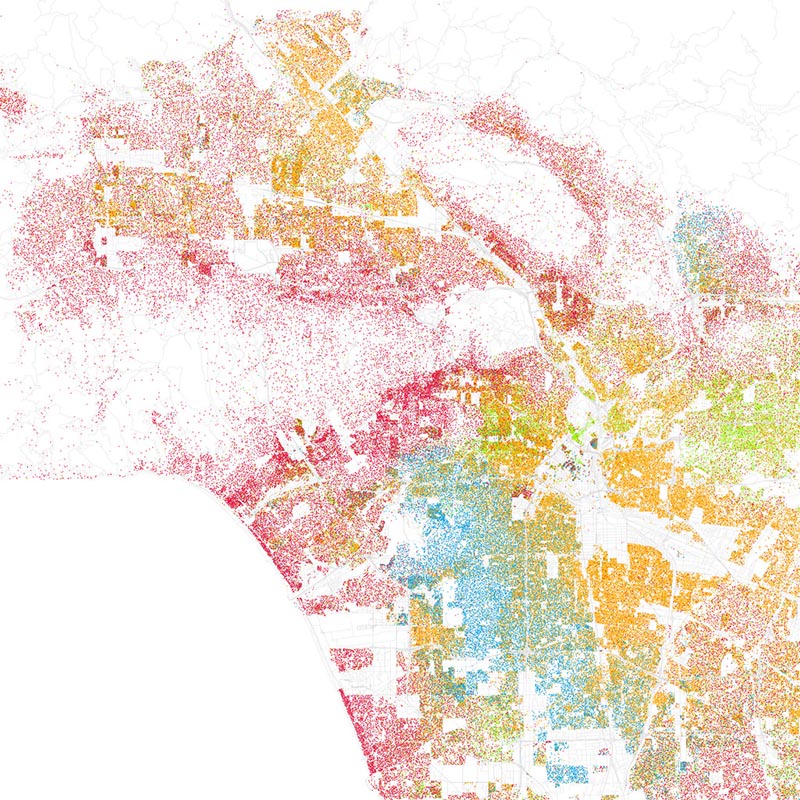

In early November 2016, ProPublica broke the story that Facebook’s advertising system could be used to exclude segments of its users from seeing specific ads. Advertisers could “microtarget” ad audiences based on almost 50,000 different labels that Facebook places on site users. These categories include labels connected to “Ethnic Affinities” as well as user interests and backgrounds. Facebook’s categorization of its users is based on the significant (to say the least) amount of data it collects and then allows marketers and advertisers to use. The capability of the ad system evoked a question about possible discriminatory advertising practices. Of particular concern in ProPublica’s investigation was the ability of advertisers to exclude potential ad viewers by race, gender, or other identifier, as directly prohibited by US federal anti-discrimination laws like the Civil Rights Act and the Fair Housing Act. States also have laws prohibiting specific kinds of discrimination based on the audience for advertisements. (read more...)