This is the first in a two-part series about the rise of citizen science, from CASTAC Contributing Editor Todd Hanson.

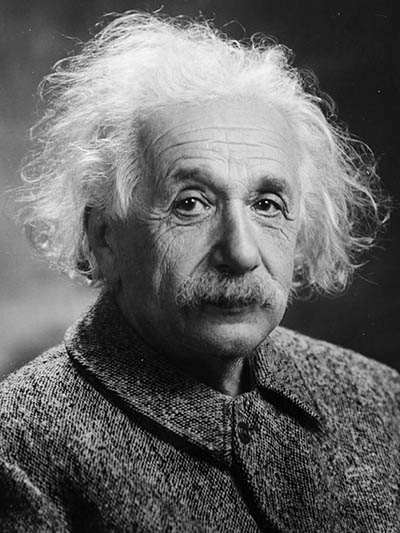

When it comes to science, Albert Einstein was an amateur. Well, at least he was during the time he made his most groundbreaking contributions to physics. From 1902 to 1908, Einstein’s day job was that of an assistant patent examiner at the Swiss Federal Office for Intellectual Property. It was during these six years as an avocational scientist that he developed his theories that transformed physics. Working as what we would today call a “citizen scientist,” the four papers he published would become a foundation of modern physics. While Einstein’s case may be unique, a lesson from his life is that ignoring the contributions of those scientists and scholars unaffiliated with university or research institutions is done at society’s risk.

Albert Einstein in 1947. Photo by Oren Jack Turner. Image courtesy of the Albert Einstein estate, public domain.

The bifurcation of scientists into professional and amateur is a relatively recent and arbitrary occurrence. Several notable eighteenth and nineteenth century “gentlemen scientists” had no direct affiliation to corporate or public institutions, including Robert Boyle, Henry Cavendish, and Charles Darwin, and were not paid scientists, or even science professors, for much or even all of their lives–but were nonetheless immensely important in the history of science. Historically, the divide increased as professional scientists were generally better educated in their fields and paid positions in universities and, later, corporations increased. Still, the general public interest in scientific matters was strong and although amateurs were rarely welcomed into science’s inner circles, they continued to work unpaid, and mostly unacknowledged on scientific matters.

Acknowledging the professional/amateur boundary as a patently artificial divide, there are groups at work today to rejuvenate the role of the independent or “citizen” scientist, such as the European Citizen Science Association (ECSA) and the Citizen Science Association (CSA). With many amateurs now possessing university degrees, keen minds, and a passionate interest in addressing matters that professional scientists admit are often too large or complex for the profession to tackle alone, the divide will potentially narrow. Success in bridging this divide may change the everyday practices of science, and by association, the ways in which anthropologists and sociologists study scientific work.

Involving citizens in science, however, is more complicated than one might expect. Simply giving, or in some cases selling, instruments to someone to collect data with, or involving groups of people in data processing, may give some nonscientists a sense of participation, but this is not genuine involvement. To be truly beneficial to all parties involved, citizen science requires a principled approach in which the critical standards, beliefs and behaviors of science are supported by competent, methodical, ethical, and intellectually balanced actions. A principled approach means bringing amateurs and professionals together in ways that truly work and matter.

Led by the Natural History Museum in London, the European Citizen Science Association (ECSA), for example, has developed the Ten Principles of Citizen Science to help guide the field. It defines a principled citizen science as being genuine, meaningful, and mutually beneficial both to citizens and professional scientists, with the research they do not only generating new knowledge or understanding, but giving the citizen scientists active participation in multiple stages of the scientific process, if they desire. In this approach, citizen scientists are not confined to data processing or other activities that do not allow genuine participation in the research.

While all of the principles of the ECSA statement are important, three of them struck me as particularly noteworthy. The first is that citizen science should be considered a unique scientific research approach with its own limitations and biases that should be considered and controlled for in the research. To me, this is an interestingly honest acknowledgement that citizen science does differ from professional scientific research, yet is not seen as inferior or second-rate. While controlling for biases and limitations may seen tedious or difficult, it is at this point that the professional scientist earns his or her keep by formulating a research approach that accommodates them.

The second noteworthy aspect of the ECSA statement is the demand for acknowledgement of the work of the citizen scientists in resulting research publications. In science, publications are the lifeblood of practice. The protocols, traditions, and rituals that govern scientific communication and publication are the stuff about which ethnographic dissertations are written and even slight changes to a such a ritualized tradition can be culturally traumatic to its long term practitioners. However, if the principled values of science practice are to be upheld in citizen science, then the contributions of all, including citizen scientists, must be acknowledged in public and in print.

Finally, the ECSA statement expects the public availability of research project data and open access publishing to be part of citizen science practices. Here, the ESCA has stipulated one of the most fundamental tenets of scientific research, transparency, as a mandate of citizen science. Without it, citizen scientists can be exploited with no substantive intellectual involvement in a science project.

Not to be overshadowed by European efforts, the Citizen Science Association (CSA) provides an equally principled approach to constructing what it calls “a community of practice for the field of public participation in scientific research.” CSA has made its mission the advancement of citizen science through communication, coordination, and education, with goals of (1) establishing a global community of practice for citizen science, (2) advancing the field of citizen science through innovation and collaboration, and (3) promoting the value and impact of citizen science. Additional goals include (4) providing access to tools and resources that further best practices, (5) supporting communication and professional development services, and (6) fostering diversity and inclusion within the field of citizen science.

Ultimately the rise of citizen science has the potential to reshape the landscape of scientific research practice. As the ECSA has noted, effective, inclusive citizen science that is genuine, meaningful, and mutually beneficial is a scientific research approach with its own limitations and biases that must be considered and controlled for in research design. It is science practiced differently in order to mutually benefit from both the opportunities for public engagement it provides and the democratization of science it engenders. Things are bound to change as citizen science continues to grow.

Meanwhile, other efforts are underway to to build the field that make it much quicker and easier for citizen scientists to connect with professional researchers, and contribute to research. But that is a point I will discuss in my next CASTAC post, The Rise of Citizen Science Part II. See you soon.

1 Trackback