In May of this year, Danish researchers released a data set containing the profile information of 70,000 OkCupid users. OkCupid is a free online dating site to which, as you would expect, users post information in hopes of making a connection. The researchers collected this data by scraping the site, or using code that captures the information available. The data set included usernames, locations, and the answers to the personal questions related to user dating, sexuality, and sexual preferences. In other words, the researchers published personal information that the dating site users would expect to remain, at least theoretically, among the other members of the dating site, and could also be used to discover the users’ real names. But should OkCupid users, and the denizens of social media in general, expect what they post online to not be made “public”?

In my last blog post, I briefly pondered the normalization of doxxing and what that means for privacy online. My question, for the most part, was whether courts would see how common doxxing has become as an indication that it is not as highly offensive to a reasonable person as necessary for a judgment of invasion of privacy. In that post I focused on doxxing by individuals, and sometimes the media. It’s important to note, however, that researchers have begun to participate in the same kind of behavior with little to no remorse. Which leads to what I think is the overarching question of what expectation of privacy people can have in information that they place on social media or connected sites like newspaper comment forums or review sites like Yelp.

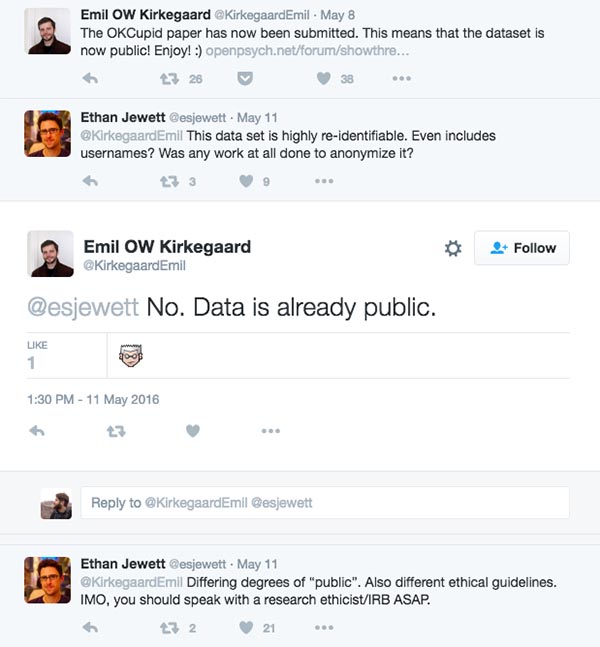

An OKCupid researcher responds to critiques about privacy on Twitter, May 2016.

Expectations of privacy and control

The extent to which we can expect privacy in our online interactions is usually undergirded by the question of what is considered “public.” When questioned on Twitter about his collection and publication of the data, one of the researchers pointed to the publicness of the data. This is important because most people work under the assumption that once something is “public,” an individual can no longer claim to have an expectation of privacy for that information. Therefore, if you are photographed while kissing someone in a restaurant, or you flash your breasts on Bourbon Street to get Mardi Gras beads, you usually can’t claim to have an expectation of privacy if, say, a news outlet gets your activity on film. A related, and just as significant, foundation for ideas about expectations of privacy is control. That is, if you exercise your autonomy—not flashing your breasts, not kissing in a restaurant—you can ensure that no one will be able to collect information about you that you do not want others to see.

Likewise, on social media, most operate under the assumption that if you tweet or post for public consumption—meaning you have not made your account private—you can’t expect what you post to remain private, particularly on sites like Twitter and Instagram, which don’t require a login to view posts from open accounts. OkCupid and other dating sites offer an additional level of security by requiring that individuals sign up with the service to view the profile information of others. Even after making an account, one could argue that there’s an inherent expectation that some of the information posted will remain among others who are searching. This is why Tinder users were upset, and many deleted the app, after finding out that someone could search for their information for $5.

What’s public anyway?

Professor Woodrow Hartzog has written about the lack of a definitive conceptualization of “publicness.” He asserts that within the context of how the term is currently used there exist three possible ways to define “public data:” anything not set to private, anything freely accessible, and anything designated public. All three of these definitions fail for various reasons, most importantly because they fail to take into account the “personalness” of the information—these data are not public records, and they don’t take into account ideas of contextual privacy.

Social media and connected sites and apps like OkCupid and Tinder demand, and have demanded for a while, a conceptualization of privacy that acknowledges the affordances of the technology and how those media are actually being used. This would mean rejecting the simplistic understanding of privacy as complete control over data—i.e., “You shouldn’t have posted it if you didn’t want it to be public.” In its place would be an approach to privacy based on relationships and human data/information flows. This is most akin to Professor Lior Jacob Strahilevitz’s social networks theory of privacy, which argues that research, like Granovetter’s on human social networks, can assist courts in making decisions about whether a plaintiff has a legitimate expectation of privacy in information that they disclosed.

Ideally we would examine how users engage with a particular site or technology to understand the kinds of expectations that they have about the information they choose to disclose. Twitter and OkCupid are both “social” technologies. And although both offer the affordance of forming relationships, one is more of a broadcast medium, the other more of a targeted communications medium. These would, then, require different notions of user expectations of privacy in the information disclosed. Users on dating sites like OkCupid and Tinder probably have a greater expectation that their information would remain private because of the affordances of those sites, than those with open Twitter accounts. So in cases like the OkCupid data leak and the Tinder search site, where the information was aggregated and made available for public consumption, a more nuanced approach to privacy in social media would demand a move away from the glib response of “it was public,” and toward an understanding of why users would want this information not to be publicly available.

References

Strahilevitz, L. J. (2005). A social networks theory of privacy. The University of Chicago Law Review, 919-988.

Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 1360-1380.

2 Comments

Isn’t the sort of simplistic dichotomy between ‘public’ and ‘private’ employed by the OkCupid researchers supposed to be addressed by ideas like Nissenbaum’s ‘contextual integrity’?

Yes, you are correct, in mentioning Helen Nissenbaum’s ‘contextual integrity’ as each user, within the context of an event and environment, has an ‘understanding,’ correct or incorrect, of the conditions in which their personal data will be spread to a wider audience. That is perhaps a taxonomic understanding of the conditions in which personal data is given and then later used or exploited.

Let’s move beyond the ‘expectation of privacy’ wherein the individual intends their data to be private and has every expectation of privacy, later, that context or expectation is not honored.

I think what Professor McNealy is trying to tease out in her piece is that there may be a third condition or violation of privacy, one that is not simply moving the private to the public, but moving the public to the ‘publicized.’

OkCupid users and other social media users have certain knowledge of what they think will public and its boundaries. But data is neither static or passive, its original meaning can be quite limited until it is either aggregated or analyzed under conditions different than the original intent of place.

I live in the Washington State which has one of the best Public Records Request laws in the country, passed by citizen’s initiative in the mid 1970s. The intent of the voters was to increase the government’s accountability to the public with heightened transparency.

Over the decades it has worked well, but no one expected, at the time, public records on individual citizen’s containing home addresses, driver’s licenses and voting histories would find their way into vast commercial databroker systems, aggregated to other data, semi private or not. New meaning is applied and new intrusions and harms possible.

This came to head, in recent years, with the well meaning intent of poetical leaders to better manage the possible abuses of law enforcement officers, by having those officers where body cameras.

Yes, it is good to have a record of an interaction between a police officer and the public, just in case there is a complaint of abuse, but what was not considered, that those same videos would be subject to public records requests.

In managing political protests police will walk past rows of citizens, wearing a body camera they are making a recording of citizen’s political activity, considered unacceptable in other clandestine attempt.

People have a certain understanding that if they visit a bar or club they are in full public view, but if a police officer enters in response to call, their camera captures everything in its view, alleged perpetrator, possible victim, employees and surrounding bystanders.

No one expects any of that to be on YouTube.