I’m a lawyer-turning-cultural anthropologist and I study rulemaking (please don’t go away just yet!).

In policy-setting circles, rulemaking has a specific statutory origin and a particular meaning, denoting a process that most federal agencies must undergo as they create policies (also known as “regulations” or “rules”). Though never a sexy topic of conversation, rulemaking is gaining public traction as a process that imposes a duty upon the government to solicit feedback from the public on proposed rules. News outlets report that President Trump is reviewing and likely revoking some of President Obama’s policies. As new presidents usually review the previous president’s policies, this is neither unusual nor unexpected. But the urgency with which such news is received by some Americans indicates an opportunity to learn what it takes to revoke or alter a rule: a new rulemaking.[1]

In sociolegal scholarship, rulemaking is a bureaucratic technicality that lays the foundation for more technicalities—such as questions of reasonableness when a rule is challenged in court. Rulemaking also works to constitute a public that must be invited to weigh in on proposed rules. Agencies that do not engage the public in this way run the risk of having their final rule invalidated by a court. How might bureaucratic processes be theorized when public participation is a required part of the process? How are comments submitted by the public obscured by other bureaucratic and legal technicalities, or by other types of knowledge?

Rulemakings’ effects are everywhere. It creates policies on everything from how foods are labeled to how much of your social security number is printed on your W-2. I returned to graduate school to learn how rulemaking is created by government officials and publics. While potential case studies are numerous, here I focus on the Clean Water Rule, long a contentious issue and one of which President Trump has called for a review.

The Clean Water Rule’s rulemaking

Upon taking office, President Trump ordered the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Army Corps of Engineers (Army Corps) to review the Obama-era Clean Water Rule to determine how to make it more consistent with the new administration’s policy goals. The Clean Water Rule is the most recent attempt to clarify over which waters the 1972 federal Clean Water Act ambiguously grants jurisdiction to the agencies. In the decades since the Clean Water Act was passed, this ambiguity has been the subject of many lawsuits and not a small amount of confusion and regulatory uncertainty for homeowners, environmental advocates, and farmers, just to name a few.

Such statutory ambiguity is not uncommon. Many federal statutes describe broad goals and leave much of the “how” to federal agencies to establish by rulemaking.

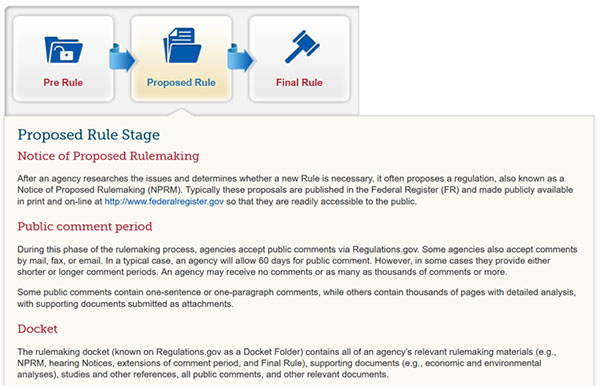

Image courtesy of Regulations.gov, “Regulatory Process: The Regulatory Timeline,” https://www.regulations.gov/?tab=learn.

By law, agencies must solicit public comment on proposed policies, which are then incorporated into the record upon which policy decisions are made. Such comments come in many forms. Some are written by advocacy groups with extensive expertise, some are the result of writing campaigns initiated by advocacy groups, and others are written by individual Americans. Bureaucrats categorize and evaluate these in an exercise that is more than just paper-pushing, one that might fundamentally shape how they imagine “the public” and how that public can shape policy.

Vernal pools are an example of waters that are jurisdictional if they’re found to have a significant nexus to a jurisdictional water. Image courtesy of the Environmental Protection Agency, “Vernal Pools,” https://www.epa.gov/wetlands/vernal-pools.

In drafting the Clean Water Rule, the EPA and Army Corps developed a record that included over 1,200 peer-reviewed scientific studies and over one million public comments. Such records are relied upon by agencies to make policy decisions and courts to determine whether a policy is reasonable (and therefore lawful). Because the Clean Water Rule is a final rule, EPA and the Army Corps must undertake another rulemaking to revoke or alter it, creating a new record of decision along the way. When the new rule reaches the courts, both records of decision—Trump and Obama administrations’ agencies’—will feature. In a sense, the courts will ignore the change in administration, leaving open the question of why the EPA and the Corps would alter the policy.

People and bureaucratic technicalities

Bureaucracies are slow innovate, slow to lead, slow to make the line in front of you shorter as you wait for a stamp on a form. Bureaucratic technicalities like rulemaking can seem clunky and wasteful of taxpayer dollars. Procedural protections like public access to information and public participation seem to add layers of process to agency actions that some believe are already determined. Such protections are often lambasted as red tape, mucking up the wheels of the state for seeming-trivial reasons. This focus on speed predominates thinking about bureaucratic mechanisms, making claims of waste seem straight-forward by obscuring the sheer amounts of scientific data, structural conditions, and perspectives that are considered in policy creation.

This is perhaps understandable, considering the esoteric nature of rulemaking. But discounting this particular bureaucratic technicality has the unfortunate side-effect of discounting the publics it creates and the roles they might play in bureaucratic processes. The publics created by rulemaking processes are diverse in demographics, political savvy, expertise, money, and influence. They are neither monolithic, nor coherent. But they influence how policy is made by contributing to records of decision. Perhaps comments are only received pro forma. But perhaps the creation of a public is something that stands on its own as a worthy and somewhat-novel endeavor: the state must seek citizens’ input as it crafts policy. What are the implications of the creation of publics in this manner for the production of knowledge within and beyond the state (Jasanoff 2004, 2011)? How does the act of soliciting comment from experts and non-experts affect the creation of a legal process (rather than the creation of a particular policy)? How might public comments become important in ways obscured by other bureaucratic and legal technicalities (Riles 2001)?

Participation mechanisms

After the 2016 elections, opportunities to have a voice in US politics exploded, with a number of organizations creating web-based platforms for calling Congressional representatives, grassroots participation in town halls, and petitions to circulate on Facebook. Each of these requires a different time commitment from participants, and is more or less available depending on leisure time, types of access, and expertise. Rulemaking has longer time horizons—as a process that creates or alters policy—and even more obscure access points that create hurdles similar to other participation mechanisms. But as I’ve shown, it offers another way to participate not only in politics, but in policy-creation more directly. It offers another way to have an impact.

[1] There are many ways to create and revoke policy, depending on how it was created to begin with, including: the passage of new legislation overriding regulations; use of the Congressional Review Act; halting rules before they take effect; and revoking executive orders and agency guidance. Each of these are different than rulemaking, potentially with different requirements for engaging with the public and making use of such engagement. For example, when Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos announced that she was rescinding Obama Administration guidance on Title IX protections for alleged victims of campus sexual assault, she carefully stressed that the new policy would come after a period of public comment. This might signal her intent to undertake rulemaking, or it may signal her intent to collect comments as the Department crafts a new guidance letter. There has yet to be announced a notice of proposed rulemaking, which would indicate rulemaking rather than guidance.

References

Jasanoff, Sheila

2004 “Ordering Knowledge, Ordering Society.” In States of Knowledge: The Co-Production of Science and the Social Order, edited by Sheila Jasanoff. New York: Routledge.

2001 Designs on Nature: Science and Democracy in Europe and the United States. Princeton University Press.

Riles, Annelise

2001 The network inside out. University of Michigan Press.