Editor’s note: This is a jointly-authored post by Lynn Schofield Clark, Professor and Chair of the Department of Media, Film and Journalism Studies at the University of Denver, and Adrienne Russell, Mary Laird Wood Professor in the Department of Communication at the University of Washington.

The Federal Communications Commission vote to end net neutrality generated weeks of stories last month — good stories — and the topic will fuel many more good stories in the months and year to come. Those stories at the intersection where technology, policy, politics and ideology meet are testament in large part to the way savvy activist communities have framed the story of net neutrality and pushed it into the news cycle. Activist-experts have made net neutrality news stories easy to write. They have articulated why internet regulatory policy should matter to the public, how it affects creative and entrepreneurial endeavor, how it has fueled but could also hobble the kind of digital innovation that has shaped daily life for hundreds of millions of Americans.

We haven’t enjoyed the same kind of coverage on the rise of “fake news,” a similarly complex story. “Fake news” is a digital-age phenomenon, a rhetorical device, a business story, a political scourge, a foreign policy threat, and more. It is as juicy a story as it is complex, and yet the mainstream media has failed to fully take it up — and, without help, the mainstream media never will fully take it up.

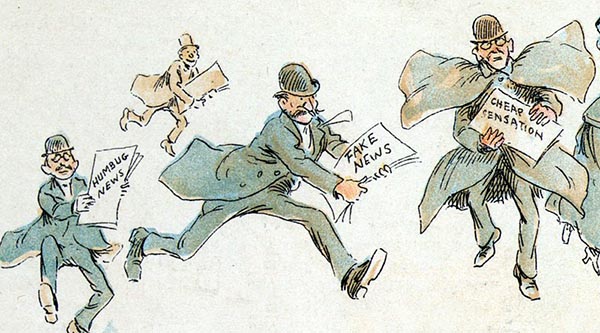

Turn-of-the-Century Purveyors of Fake News

“Important”

A day before Thanksgiving, Facebook issued an update on its plan to increase transparency about the advertisements that appear on its massively influential media platform. The news came in response to a request Congress also put to Google and Twitter following a hearing on foreign interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. “It is important that people understand how foreign actors tried to sow division and mistrust using Facebook,” an unnamed author wrote on behalf of the company.

How important was it to Facebook? It will come as no surprise that the unsigned Facebook new release was buried under Holiday distractions. The Associated Press and Politico published quick pieces that highlighted the company’s plan to create a portal where users could see for themselves which of the pages they “liked” or followed last year were produced by the Internet Research Agency, a now infamous and defunct Kremlin propaganda farm. TechCrunch, a leading technology news blog, also covered the story, criticizing Facebook for not going far enough in the cause of transparency. Four days later, Slate republished a story from an online forum for national security law and policy that described Facebook’s effort as a “pathetic fig leaf.”

Indeed, The Daily Beast reported that, during the special U.S. Senate election in Alabama last month, the same kind of “shadowy, undisclosed advertising content” that last year hyped the Trump candidacy poured into the Facebook accounts of Alabama residents. The ads this time promoted failed candidate Roy Moore, the longtime controversial far-right judge who has been credibly accused of pedophilia.

Facebook noted in response that it plans to roll out its transparency updates this summer ahead of the U.S. midterm elections.

The “fake news” storyline tied to social media advertising will extend for many more months and perhaps years to come. Meantime, many other fake news developments will continue to unfold every day. Will mainstream reporting on the topic move beyond description and reaction and instead focus coverage onto the larger forces and entrenched systems fueling fake news?

A dark assessment and a sinister twist

For better or worse, the fake news phenomena — and the responses the phenomena engender — will help shape the future of communication. It is of course a much bigger story than the president, for one, would have us believe. The term itself is frustrating. It’s a contradiction, as UNESCO’s Guy Berger has noted. “If it’s news, then it isn’t fake, and if it is false, then it can’t be news,” as he put it. The term is now overloaded. It acts as a stand-in for many complex features of the current information ecosystem — the digital space as a global information war zone, the effects of iterative, arcane and enormously influential media technologies, the rise of empowered but also media-illiterate publics, the booming news market, and its shadow, the failing journalism industry, to name just a few.

In all its permutations, fake news is the air we breathe as members of what University of Pennsylvania media studies Prof. Victor Pickard called the “misinformation society.” In an essay for the Trump-era Big Picture symposium being held by Public Books, Pickard names three factors contributing to the unfolding information crisis: anemic funding for accountability journalism; the growing dominance of infrastructure and platforms that through their business models support the spread of misinformation; and the “regulatory capture” metastasizing across governments, where agencies are staffed with regulators who support and often benefit from the commercial interests they are tasked to oversee. Those factors among others have combined to create a media landscape that seems especially vulnerable to abuse, where hucksters thrive and bogus research and disinformation land upon vast fields of fertile soil.

Many will agree with Pickard’s dark assessment. We would add a sinister twist. The information crisis he outlines is a story that some of the most popular forms of journalism today — specifically television news and print and online outlets that adhere to legacy practices — seem particularly poorly equipped to tell. Too often, coverage on the fake news information crisis fails to shed light on key issues — on the values embedded in new tools and infrastructures, for example, on the way the information society as it is being built exacerbates social and economic vulnerabilities, on how we might take action to make things better and, perhaps most significantly, on the tension between the interests of corporate media and the interests of the public that journalism is supposed to serve. The struggle among news outlets to powerfully report on such topics will come as no surprise to anyone who has been paying attention to changes in the news industry over the past two decades.

As many have noted, journalism today is being redesigned on the fly to suit distribution systems created by the digital-tech entrepreneurs behind Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon. Nearly four decades into the digital revolution, journalism business models are still struggling to find stable footing. Local journalism continues to wither, billionaires gobble up larger shares of the market, and corporate consolidation continues apace. The fact is, the sad state of affairs today only stokes the tension long at the center of the journalism enterprise in the United States between what’s good for business, and what’s good for the public. There are plenty of examples of how that tension has shaped journalism reporting and publishing over the decades, but the way it has shaped news-cycle reporting and the selection of events and people deemed newsworthy is particularly relevant to the quality of coverage we’re likely to see on the information crisis.

Journalism values

Over the course of decades, researchers have explored ways certain values have shaped the procedures and structures of journalism. Indeed, the way the Fourth Estate operates is now so familiar that gamesmanship is factored into the operation. Communication shops have long worked a sort of see-saw relationship with reporters. Corporate and government spokespeople attempt to “manage” news cycles by in part pushing some stories and burying others. They know that reporters — now perhaps more than ever before — prize immediacy and that news outlets privilege stories that are timely. That’s why Facebook posted its transparency release the day before Thanksgiving and succeeded in garnering mostly short pieces published on a day when relatively few people would read them.

Reporters tend also to play up conflict and highlight individual actors. Thus, as Stanford University Political Science Professor Shanto Iyengar has shown, they cover social issues as a series of episodes, where a particular instance of conflict stands in for the larger problem of, for example, systemic racial bias in the criminal justice system. The episodic approach tends to encourage attribution of both the problem and the resolution to the subjects who appear in the reported stories. The effect is that complex issues tied to technology developments and media regulation and public policy formulation, for example, appear either in the breathless tone of the unfolding episode or in a style that focuses on key players, often at the expense of the bigger picture. These issues, combined with journalism’s tendency to privilege bureaucratically credible sources, in this case tech industry leaders and politicians, creates coverage that papers over enduring problems and works to downplay the power of larger societal conditions.

These weaknesses are exacerbated by the fact that journalists also tend to cover stories about journalism uncritically. Outlets readily acknowledge that huge data sets describing reader and viewer habits are transforming news rooms, but they tend to focus on the ways the data makes it easier for them to engage with their audiences and come to editorial decisions. Individual writers and editors certainly grouse about having to produce click-bait stories, but few outlets have constructed a beat around the way user data and related technologies may be working to expand territory falling into the misinformation zone. There is a blindness tied to the way increasing reliance on user preference data has come to structure the overall industry and its business models. In other words, data tracking and analysis has become a tool for journalism’s survival within a capitalist support system, and questioning the values behind this new profit model rarely appears on the publishing agenda — not least because U.S.-based journalism has long treated capitalism itself as mere common sense.

The professional and business-related biases in favor of timeliness, on episodic story-telling, on spotlighting individuals who occupy positions of authority, on delivering short and upbeat stories on technology issues — all of these practices and inclinations combine to steer journalism away from larger questions of how technology and news industry business models are mixing in the information ecosystem to shape new technologies and values and effect larger social and political realities.

Technology values

There are values embedded in technology. This isn’t something widely understood, partly because journalism often uncritically relies on the perspectives of tech-industry leaders, and tech entrepreneurs and developers aren’t being paid to consider the way what they’re building influences how we think and act. A growing body of work on values in design supports the premise that communication technology is no neutral medium but that it powerfully asserts social, political, and moral values. Certain design elements enable or restrict how technologies may be used and by whom. Design can cater to male or female users or straight or queer users or rich or poor users. It can lead us believe some data is important and other data irrelevant, and so on.

The net neutrality debate has underlined this quality. The internet as it has been designed intentionally so far is a so-called dumb network, because its transmission control protocol (TCP) makes no decisions about content — every IP address is treated equally on the network; no IP address receives preferred treatment. There results of that design have been dramatic. For three decades we have enjoyed at the same quality and speed sites created by happy cat people on a limited budget and those created by multi-billion dollar companies like Wal-Mart and CNN. The protocol fosters innovation because creating a new application does not require anyone to change the network. The World Wide Web runs atop the internet as it was made, so do voice and video files and so do social media services. None of the inventors of these technologies had to modify internet protocol. By contrast, the phone system is a “smart network,” whose services depend on the central switches owned by the phone company. There is little room for innovation on the phone network. “Sure, you can make a phone look like a cheeseburger or a banana, but you can’t change the services it offers… centralized innovation means slow innovation,” wrote technologist Andreas M. Antonopoulos. “It also means innovation directed by the goals of a single company. As a result, anything that doesn’t seem to fit the vision of the company that owns the network is rejected or even actively fought.”

Have news media translated that view for use in the debate over fake news? Mark Zuckerberg and Sheryl Sandberg consistently claim that Facebook is a technology company, not a media company, and in doing so, they lean on the impression that technology is a neutral medium. They sidestep the responsibility that would come from acknowledging that there exists a variety of content that the Facebook platform prefers to generate and circulate. From that standpoint, “Facebook can claim that any perceived errors in Trending Topics or News Feed products are the result of algorithms that need tweaking, artificial intelligence that needs more training data, or reflections of users,” as University of Southern California Communication Professor Mike Ananny put it “Facebook [can] claim that it is not taking any editorial position.” Indeed, Facebook, Twitter and Google have moved between blaming human and algorithmic error for various public debacles. Twitter blamed human error when a New York Times account was blocked on November 26. The same when President Trump’s account was blocked for 11 minutes earlier in the month. But it claimed an algorithm was at fault when a hashtag generated in the aftermath of the Las Vegas shootings had misspelled the name of the city. Facebook blamed humans for bias in its trending topics then blamed algorithms for allowing advertisers to market products to “jew haters.” The back-and-forth blame game disorients people following the “fake news” story and obscures the fact that algorithms, like human employees, act according to the values cooked into their innards. Humans with values make humans who think like they do, for good and bad. Same for machines and for software and algorithms.

Properly informed members of the public might more easily recognize that effective algorithm-driven machine learning requires enormous amounts of user data and that, for that reason, the hungry algorithms result in aggressive surveillance of users. This is true beyond social media. User surveillance is now driving the business models of companies across industries, including the journalism industry, such as it is. Rather than relying on ad buys, media companies sell user data. Is it a surprise that, as our research demonstrates, news organizations have not done a particularly good job covering issues related to surveillance and receding privacy norms or, in other words, surfacing the downsides of an economy that sees personal data as the new oil — an immensely valuable asset, the extraction of which comes with enormous downsides?

Tech company spokespeople simply are not the best sources to consult on the wider implications of algorithm design. Frank Pasquale, Professor of Law at the University of Maryland and author of The Black Box Society, has argued that algorithmic accountability is “a big tent project,” that “requires the skills of theorists and practitioners, lawyers, social scientists, journalists and others.” Pasquale’s recent testimony before the U.S. House of Representatives combined the expertise of all of these fields to identify examples of troubling collection, bad or biased analysis, and discriminatory uses of algorithm-based technology — all of which work to exacerbate existing social and economic vulnerabilities. To cover the information crisis, journalists must deepen their sources on technology.

Exacerbated vulnerabilities

Just as the case with values in design, episodic coverage that emphasizes the perspectives of Silicon Valley executives does not tend to address issues of inequality. Revelatory incidents tend to be reported in isolation, which masks the way they are structural in nature. If the FCC rollback of net neutrality goes unsuccessfully challenged, people who can’t afford to pay for faster internet speeds will find themselves at an even greater disadvantage than they are experiencing today. They may be priced out of the innovation game, blocked from entering the startup society. Digital-age free expression and activist organizing may also be limited. Carmen Scurato, director of policy and legal affairs for the National Hispanic Media Coalition put it this way: “Dismantling net neutrality opens the door for corporations to … impose a new tool to access information online. […] For Latinos and other people of color, who have long been misrepresented or underrepresented by traditional media outlets, an open internet is the primary destination for our communities to share our stories in our own words — without being blocked by powerful gatekeepers.”

There is little news coverage of how algorithms and other forms of artificial intelligence can be discriminatory, especially to groups already vulnerable. While investigative journalists at outlets like Propublica and the New York Times have exposed such discrimination, it is easy to miss coverage of, for instance, the way credit card companies collect data on the mental health to predict future financial distress, which means a visit to a marriage counselor might translate as a downgraded credit rating; the way Facebook algorithms programed to deliver housing ads screen out people of color; the way Google algorithms deliver ads for services like background checks for criminal records alongside searches that include any typically African-American name; the way prices for products or enticements to buy change depending on whether you make a purchase from a low-income zip codes.

The same kind of user data fuels misinformation campaigns. Algorithms have been used to tap into people’s intellectual and psychological vulnerabilities. Online evidence of affiliation with racist groups or resentment toward certain ethnic groups signal a user will be receptive to made-up stories that fuel such bias. The same stories would be directed away from audiences likely to call it out as false. Young people of color demonstrate heightened awareness about the ways data can be used against them, according to our research. This is perhaps what makes them as a general group the most savvy but also the most self-censoring users of digital media. It is clear that increased circulation of hate speech pushes already marginalized groups further to the margins. The well documented lack of diversity among tech creators, journalists and social media influencers threatens to reinforce viewpoints and experiences of those in positions of privilege at the expense of everyone else.

An expanded journalism

There remains a world of information beyond news, real and fake. There is a growing movement to hold the task-masters of artificial intelligence accountable. Research collectives like NYU’s AINow, MIT’s Data for Black Lives, and Cardiff University’s Data Justice Lab, and the cross-institutional Public Data Lab, all do work on the real-world implications of algorithms and related technologies. A report by AINow highlights cases where these systems are being used without prior tested or assessed for bias and inaccuracy. The report calls for an end to so-called black box predictive systems at public institutions — such as the criminal justice and education systems. A report by Public Data Lab provides a useful guide to tracing the production, circulation and reception of “fake news” online.

Sites like The Conversation, Public Books, and Medium, and the opinion pages of newspapers like the New York Times and the Guardian host essays by scholars studying dubious data production and AI practices. Jenny Stromer-Galley, Professor and Director for the Center for Computational and Data Sciences at Syracuse University, wrote on simple ways Facebook could reduce fake news; Siva Vaidhyanathan on how Facebook benefits from fake news; Zeynep Tufekci on Zuckerberg’s Preposterous Defense of Facebook after the election.

The point is, academic and journalistic investigations, policy recommendations, informed criticism and thoughtful commentary on the information crisis are rumbling under the cable news noise. Mainstream journalists have to spend too much energy working a system littered with obstacles that keep them from meeting the challenges posed by the information crisis. The task is falling to outside thinkers, to academics, activists, technologists and others to shed light on the true contours and nature of the fake news story.