By: Elena Parmiggiani, Helena Karasti, Karen Baker, and Andrea Botero

The environmental sciences have been a fertile ground for the development of scientific infrastructures (a.k.a. cyberinfrastructure in the USA and research infrastructure in Europe). Their promises of addressing grand challenges such as climate change require increasing collaboration as well as new forms of research based on data sharing. However, infrastructure policy work in this domain has proven arduous. The environmental sciences are intrinsically heterogeneous with variations in data that must be navigated across local and global scales, ecological variety, societal concerns, and funding structures.

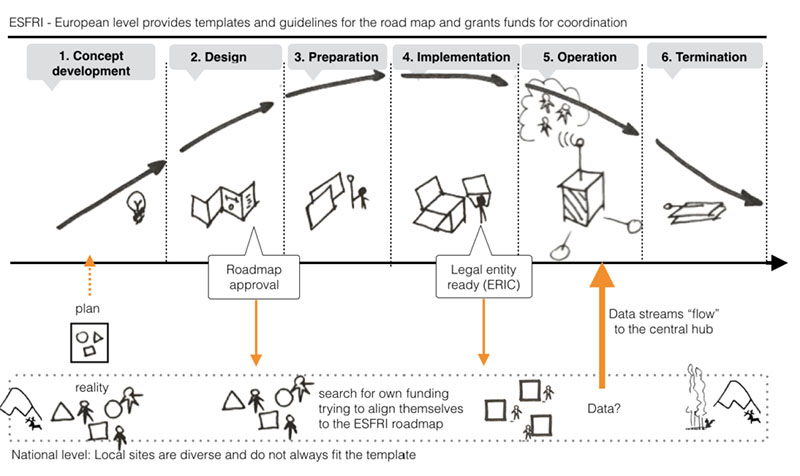

Figure 1. The upper panel shows a simplified view of the ESFRI 30-year research infrastructure formation strategy. The lower panel has been added by the authors to make visible local data management and infrastructure work that requires not only attention but also funding if it is to design and operationalize data flow to a central hub (Source: Drawing by Andrea Botero).

Different research policy regimes have emerged in different countries to regulate scientific infrastructures. The European Union (EU) is a supranational entity currently encompassing 28 countries, each with its own national research policy and funding systems. The EU’s scientific infrastructure policy mindset has taken a hierarchical regulatory approach to handling the heterogeneities across countries with the aim of establishing pan-European Research Infrastructures (RIs). The EU-funded RI initiatives tend to be top down, serving the EU’s goal of integrating national research systems also on the epistemic level[1].

The main policy program regulating RIs in the EU is the European Strategy Forum on Research Infrastructures, or ESFRI[2]. The ESFRI roadmap is an obligatory passage point; it is practically the only funding mechanism for most large domain-specific RIs, therefore being formally accepted onto the ESFRI roadmap is crucially important for any RI seeking funding (Figure 1).

The mutual shaping of policy and scientific infrastructure

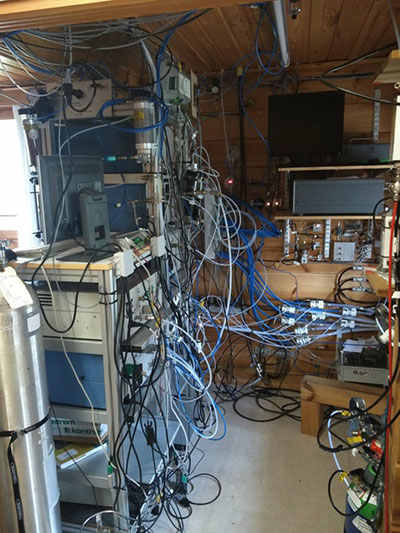

Figure 2. Left: Environmental monitoring at a highly instrumentalized research station in Finland. Data produced here are shared with several national and European research infrastructures (Photo Helena Karasti).

Infrastructure is always political. There are tensions between practice and policy, where policy often embodies visions of innovations, vested interests, control regimes, and struggles to accommodate the inherent heterogeneity of local day-to-day practice[3] (Figures 2 and 3). Throughout more than a decade of engagement with the formation of RIs for environmental research in the EU, we have observed that, despite its aim to unify and integrate, the ESFRI itself inflicts fragmentation as an unintended side-effect. This has given birth to an almost paradoxical situation, where the pan-European politics for inclusiveness and integration on the policy level often triggers exclusions, gaps, and splintering of RIs, followed by protracted processes of learning and corrective measures. This is vividly exemplified by the efforts of the European Long Term Ecological Research (LTER-Europe) network to acquire formal status on the ESFRI roadmap, and hence also acquire funding. It highlights the differences between top-down and bottom-up efforts and also illustrates gradual accommodations over time as local and national efforts interface with the higher-level policy-centric approach of supranational mechanisms such as ESFRI. This oscillating process causes splintering and exclusions on both the European and national level.

Figure 3. Inside the data-hut located near the instrumentation in the forest (Photo Kristjan Adojaan; reproduced with author’s permission).

On the European level, the formation of RIs is challenged by the high political heterogeneity that characterizes the member states. As a consequence, despite the centralizing efforts, the cause of splintering has often been political rather than scientific. For example, some of the original national members of LTER-Europe network have been left out of the recently proposed ESFRI eLTER RI, because they were unable to raise the required endorsements from their governments before the application deadline. Splintering and reduced inclusion also occur later in the ESFRI process, when the participants in an RI must apply to gain legal status as European Research Infrastructure Consortium (ERIC, see also Figure 1). The ERIC was established for the ESFRI roadmap as the main instrument for ironing out any cross-country heterogeneities, requiring all RIs to become legal entities and not simply networks of research sites. A second round of splintering seems therefore possible for the eLTER RI, should it become accepted on the ESFRI roadmap. The requirement for financial commitments from the governments of all participating member states in the ERIC phase represents a major challenge to pan-European infrastructure making. In this process, unacknowledged differences across countries come to the fore in terms of availability of funding resources and the possibility for researchers to obtain stable enough governmental support on the national level.

There are currently some adjustments underway. On the one hand, EU policy makers are making efforts at gradually balancing the uneven availability of research funding, for instance by starting to direct regional funds to RIs in the less developed areas of Europe. On the other hand, a new rhetorical drive accompanies this gradual shift: the language associated with the RI policy has recently changed, from the notion of ‘pan-European’ to ‘multi-lateral’, signalling that the ideal of a pan-European participation is perhaps no longer viable. The evolving relationship between policy and RI formation also has consequences in terms of the definition of a hybrid researcher profile that is new to researchers in EU. By following the formation of environmental RIs, we have observed that this process requires researchers to be not only good scientists but also skilled managers and policy-savvy negotiators. However, environmental researchers often resist and question this change, struggling to recognize the value of the political and managerial abilities that are increasingly necessary to participate in RIs.

The ESFRI process also generates fragmentation and exclusions on the national level, which are emphasized by the climate of rationalization after the recent economic crisis. It is crucial to follow unfolding processes on the national level in order to understand the learning paths that each country must take in order to accommodate EU-level policy in local political and financial systems. Each member state is encouraged to set up a national roadmap describing their RI policy and funding. This is, naturally, achieved in a variety of ways across the EU. The case of Finland is interesting: Finland was one of the very first countries to establish an RI roadmap in 2008, and hence had to learn to navigate the ESFRI process as it was being implemented. In the beginning no funding was attached to RIs included in the national roadmap, as it took the Academy of Finland until the second edition in 2014 to establish an appropriate RI policy with funding. For example, the Finnish Long-Term Socio-Ecological Research (FinLTSER), was on the first national RI roadmap but eventually failed to obtain national funding.

During the same years, environmental research in Finland had gone through a rationalization process, including reduction of research/field stations as well as cuts in personnel and resources. As part of an informal integration process for environmental research that followed, some of the research stations of the FinLTSER network were merged into a large consortium. However, since this consortium includes only some of the original FinLTSER sites, only they have become partners in the European level ESFRI eLTER RI proposal. To complicate matters further, the eLTER RI proposal puts forward a hierarchical classification of research sites that acts as a prioritizing criterion for resource allocation. As the categorization of sites has yet to be carried out in Finland, prioritization and maybe even more exclusions of the initial FinLTSER sites may be expected.

An agenda for (re)integrating policy and practice in infrastructure

The story of ESFRI makes it clear that heterogeneities never just ‘go away,’ but tend instead to be harmonized in order to meet top-down expectations, sometimes painfully. Ours is also a cautionary tale, showing that the notion of a ‘build-it-once’ or a ‘one-size-fits-all’ infrastructure policy is wrong-headed. Rather, scientific infrastructure formation is a reflexive learning process where researchers, developers, and policy makers gradually learn to learn together about creating effective infrastructure at unprecedented scales and scopes. The categories created in the ESFRI policy template and in the individual proposals are still top down efforts, yet they are evolving—though at any given moment they may function as tools of exclusion/inclusion and prioritization.

One lesson to be learned from our decade of engagement with RI formation is that infrastructure policy is a slow, concerted effort of dealing with emerging heterogeneous tensions over time, which in the EU setting involves national, European and multi-lateral policy levels. Scholars of the sociotechnical have long proposed using the transitive verb “infrastructuring,”[4] in its gerund form, to describe the relational, processual, emergent nature of infrastructure-making and policy as evolving endeavors that cut across established disciplines and development phases.

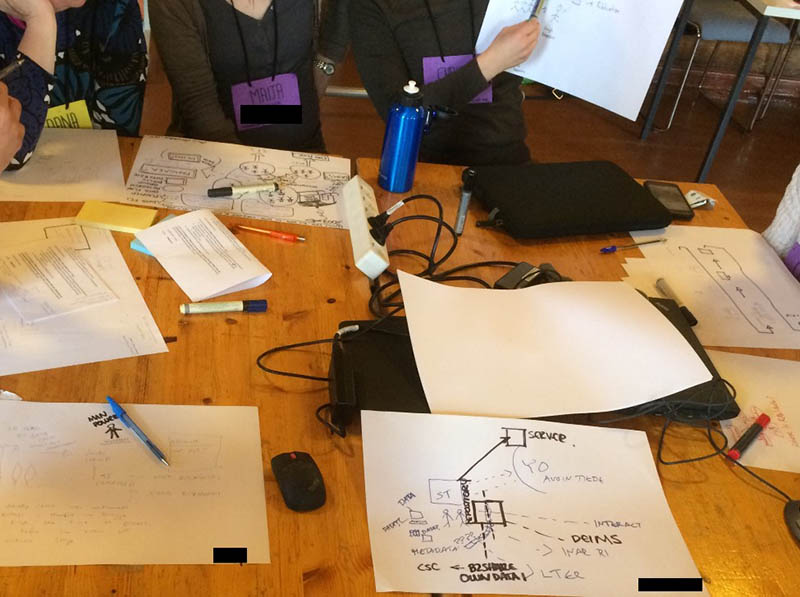

A working group during a workshop organized by our team to discuss data management. Each participant was asked to draw and present how data are managed and shared at their research station/location and within the larger context of networks and multi-lateral efforts. (Photo by the authors).

So what does it mean for researchers to adopt an infrastructuring lens? We as researchers (including both infrastructure scholars and domain scientists) have a political role to play in supporting the reintegration of practice and policy by establishing and maintaining relations in infrastructure. We can actively intervene with participatory approaches (Figure 4) by addressing the tensions that exist between bottom-up and top-down efforts and thereby supporting collective reflection and change thinking rather than stasis or confrontation, recognizing that there are always multiple intentionalities at play.

In sum, this calls for a renewed sensitivity to policy work, to bring policy back into the picture in order to be better placed to inform the work of national and transnational funders. That is, scholars of infrastructure should consider themselves an integral part of the (huge) machinery of infrastructure formation and policy-making. This entails an effort to conduct longitudinal, multi-scope, and engaged studies[5] of how policy and practice of scientific infrastructure co-evolve.

References

[1] Kaltenbrunner, W. (2017). “Digital Infrastructure for the Humanities in Europe and the US: Governing Scholarship through Coordinated Tool Development,”Computer Supported Cooperative Work (26:3), 275-308

[2] Stahlecker, T., & Kroll, H. (2013). Policies to Build Research Infrastructures in Europe – Following Traditions or Building New Momentum? (Working Papers Firms and Region No. R4/2013). Karlsruhe: Fraunhofer.

[3] Appel, H., An, N., and Gupta, A. (2015). “Introduction: The Infrastructure Toolbox — Cultural Anthropology,” , September 24. (https://culanth.org/fieldsights/714-introduction-the-infrastructure-toolbox, accessed January 18, 2017); Karasti, H., Millerand, F., Hine, C. M., and Bowker, G. C. (2016). “Knowledge Infrastructures: Part I,” Science & Technology Studies (29:1).

[4] Star, S. L., & Bowker, G. C. (2002). How to Infrastructure. In L. A. Lievrouw & S. Livingstone (Eds.), Handbook of New Media: Social Shaping and Consequences of ICTs (pp. 151-162). London: Sage Publications.

[5] Karasti, H., & Blomberg, J. (2018). Studying infrastructuring ethnographically: Constructing the field and delineating the object of inquiry. Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 27(2), 1-33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10606-017-9296-7

2 Comments

Nice piece all — very interesting.

Hello Karen Baker — long time no see!~

Bonnie Nardi

Thank you Bonnie for the supportive comment!