I’m meeting a fellow speech therapist researcher at a weekly drop-in session for people with aphasia when Markus* comes in, brandishing an envelope. “I went!” he exclaims.

Markus has just arrived fresh from a visit to the head office of one of his home utility providers. He has taken matters into his own hands after coming up against a technological obstacle. Markus regaled to us his story using an effective combination of short spoken utterances, gesture, a written note and an established communication dynamic with my fellow speech therapist. I want to share with you his story to discuss the issue of technology and aphasia.

Markus had received a letter telling him that his boiler (the British term for a home water-heating system) needed to be serviced. The letter instructed him to call or go online to make an appointment. Due to his aphasia, however, Markus had found himself unable to fulfill this request. It has been several years since Markus’s his stroke, and – whilst his physical symptoms have largely been restored – words often still evade him. The aphasia Markus developed because of his stroke has impacted his (previously typical) ability to use language. This makes it difficult to say the things he wants to say and to write the things he wants to write. It also makes it more difficult to extract meaning from the spoken utterances and written sentences of others. With time, and in person, however, Markus can usually get his message across. However, requests to “call or go online” will pose difficulties.

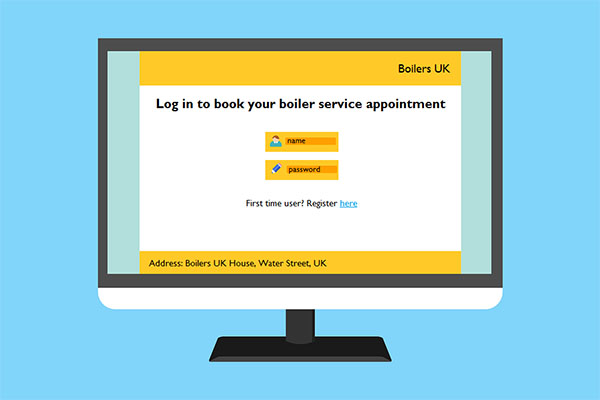

Example of an appointment log in screen. Registration processes, passwords and long strings of text can all pose challenges for technology users with aphasia. Figure: Abi Roper, 2018

Markus is one of around 450,000 people in the UK (Stroke Association, 2018) and 2 million people in the USA (National Aphasia Association, 2018) living with aphasia. Just as for other disabilities, everyone with aphasia is different – each person experiences a different combination of communicative strengths and challenges, though their intellect typically remains unaffected. On top of affecting their everyday lives, the sudden language impairments effected by aphasia can have a dramatic effect on people’s ability to interact with technology, thus revealing the scale of the linguistic demands that even very basic technological interactions, such as searching through a drop-down menu, acknowledging a pop-up about cookies, signing into a social media site, or booking an appointment online can place upon our language system. An increasing number of our daily interactions however, are now carried out online – with recent figures from the UK telecoms regulator Ofcom indicating that whilst a growing number of us now own smartphones, a decreasing number are using these to make phone calls, despite the fact we are using them on average every 12 minutes. For many of us, the capacity to complete myriad activities online provides an increased efficiency and flexibility when undertaking any number of daily tasks, from paying the electricity bill to more readily being able to update friends or family about our feelings, thoughts, and plans. For people with aphasia, the growing move towards web-based communications can pose challenges.

That is not to say that technology cannot be a boon for people with aphasia in other ways. Francoise*, who also attends the same aphasia drop-in as Markus, has almost no spoken language at all, and yet, with the help of her smartphone camera gallery and google maps, she can take you on a virtual world-tour, sharing stories of her abundant travels and cultural exploits. Similarly, through the use of speech-to-text technology which capitalizes on his comparatively well-retained spoken skills, Australian stroke survivor Paul Fink, has written an illuminating blog post, documenting the many technologies he has adopted within his life-after-stroke journey:

“Before my stroke, I was very fast at touch-type and I used the computer keyboard with work, through muscle memory, but I am struggling to write in general – Doesn’t matter typing or physical writing – because my brain I have difficulty with compute the letters. I mainly use the mouse for computer stuff now, but I am definitely improving this area.”

Embracing and utilising technology after my stroke, Paul Fink, I am Paul Fink

As a speech and language therapist and researcher, I am inspired by the many possibilities technology might offer people with aphasia to communicate and actively build and maintain social relations. Indeed, much of the research I have been involved in has found evidence for the benefits technology can afford within the aphasia therapy process.

I’ve seen first-hand that well-designed technology can support structured therapeutic practice. One such example comes from GeST, “a therapy tool designed with and for people with severe aphasia in order to train a ‘vocabulary’ of everyday communicative gestures” (Roper et al, 2016). Another example comes from SWORD (Varley et al, 2016), and a final one from EVA (Marshall et al, 2016). I have seen each of these technologies empower people with aphasia to re-connect with others.

Using computer therapy, GeST, to practise a gesture vocabulary at home. Image: City, University of London, 2012

Indeed, there is a growing evidence base that, in combination with tailored training and a practice schedule, people with aphasia can continue to make language gains many, many years after their stroke (NIHR, 2018). My first-hand experiences have also revealed to me the many of the limitations of technology, however, and whilst very structured and patiently-practiced therapeutic activities can definitely lend themselves to administration via technology, other, less predictable and unsupported interactions can often prove seemingly impenetrable. This is not to say I don’t believe these must be permanently out-of-reach. Indeed, INCA (INClusive digital content for people with Aphasia), a research project with which I’m currently involved, aims to address some of these very challenges and support a greater number people with aphasia to be able to create and curate digital content – for example, by creating and sharing poetry, videos or music via an accessible interface. We hope that this work will also go some way to giving people with aphasia an online digital presence, so they might be more readily considered when companies are producing technologies and pursuing digital engagement.

In the meantime, where there is a will, there is a way. Markus decided to address his boiler appointment challenge with the help of a pre-drafted letter he had stored on his PC. The letter went something like this:

“I have aphasia because I had a stroke.

I can’t talk on the phone.

I AM NOT STUPID!”

Armed with his letter, plus the original boiler service request, Markus set off across town to the visit the return address he had found listed on the request’s envelope – an address that turned out to be not a service center but rather the company’s head office. Upon arrival, using his extensive face-to-face communication skills, Markus explained to the building receptionist his issue. She telephoned the number given on his letter and booked a boiler service appointment on his behalf. Issue resolved, Markus set off to meet us at the drop in and report his victory.

For me, Markus’s ingenious, and very human, problem-solving response to his technological obstacle serves to illustrate that there is still a fair amount of human endeavor required if we wish to reduce the disabling potential and engage the enabling potential of technology for people with aphasia.

*Identifying details have been changed to protect anonymity.

1 Trackback