Ethnographic explorations with sex dolls, robots, and their makers

“I hate it when her eyes flick open. This one, her eyeballs sometimes go in different directions and it looks creepy.” Catherine reached over, gently pulling the doll’s eyelids down with one extended finger. The doll, Nova, was petite, shorter than Catherine and I, and had jet black hair and brown skin. She had been clothed in a white unitard suit. Nova was flanked by other dolls of various heights and skin tones, to her right a white-skinned brunette, also a “petite” model, and across from her, a life-size replica of the porn actor Asa Akira. Henry, a newer model, stood beside Nova. He had been dressed in what might be described as office-kink-lite, a white button-down shirt and black slacks, along with black fingernail paint and a leather wrist cuff. His skull was cracked open to reveal the circuitry inside. Henry, Nova, Asa’s doll, and the others were standing propped in the display lobby of a sex doll manufacturer’s headquarters in southern California. I visited the headquarters in the spring of 2018 to meet the dolls and their makers. Catherine, the company’s media liaison, generously offered me a tour of the display showroom and production site.

Sex dolls have always enjoyed a certain celebrity and intrigue. This particular company, which had been in the market for over 20 years, proudly highlighted sex dolls’ recent pop history with magazine clippings and gallery walls of movie posters. Most of us have peripheral engagements with sex dolls as femme bodied robots. These robots, like Maria in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis or Pris in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, are often hypersexualized automatons who augur the apocalyptic ends of men’s capitalist, technological excess. Janelle Monaé’s reinterpretation of Maria as Cindi Mayweather, the Afrofuturist ‘archandroid,’ highlights how robots have typically served as vessels for white masculine anxieties around enslavement, consent, and freedom.

Showroom doll with movie posters for Surrogates and Lars and the Real Girl.

My ongoing fieldwork considers speculative fiction and ethnographic encounters with robotic dolls and their makers to explore questions of proximity, desire, and the policing and prevention of violence. Realistic silicone sex dolls have been commercially available for over three decades, with customizable skin and hair, replaceable and interchangeable genital and anal cartridges, and adjustable joints and limbs. Mark, the graphic designer for a doll company, explained that “We have a very, very customizable product and we advertise as much.” Clients with a flexible budget can request most humanlike specifications, although Mark was quick to clarify, “we won’t do anything that involves whatsoever children or animals or things like that.” A fully customized doll can easily run a $50,000 sale price.

The dolls offer a degree of verisimilitude, but ‘not quite,’ that many users locate as itself the site of pleasure. Users insist, unequivocally, in interviews, forums, and documentaries, that sex with the dolls is not simulated but real sex. For some, the doll or the robot is itself the site of erotic arousal and attraction. The international conference “Love and Sex with Robots,” is in its fourth iteration and organized around this point of exploring the contours of robo-sexual attraction.

“Maria” from Metropolis (dir. Fritz Lang, 1927)

I consider the realism of the dolls with regards to customizable skin tones. The silicone flesh of the dolls is heatable and textured, with a supple give when pressed. The doll company uses a template of six baseline colors from which all custom colors can be mixed. Mark explained that “you’re trying to assimilate what their skin tone is to match it with the silicone,” and that a designer might experience challenges in trying to match skin tones in different lighting. As I toured the doll production factory room, most finished dolls were dyed in skin hues approximating white or light brown, with a smattering of darker-skinned dolls. I did not see any “unusual” skin tones, although Catherine mentioned that blue “Na’vi” skin from the movie Avatar (2009) had been popular for some time.

“Pris” from Blade Runner (dir. Ridley Scott, 1982)

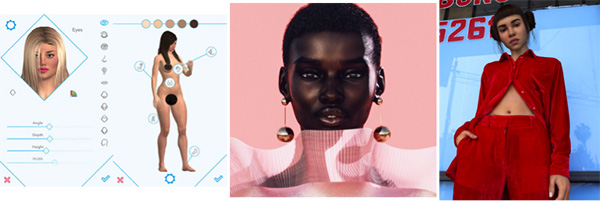

In the past few years, some doll companies have begun experimenting with embedding AI features into user experiences of their doll. RealDoll launched a beta version of its Harmony AI app this past April, where users can modulate a customizable avatar’s voice, tone, and accent. The AI will eventually be paired with a robot head, with a retail price estimated around $10,000. Harmony AI is, as some have pointed out, the real version of “Joi,” the holographic femme personal assistant featured in Blade Runner 2049. The Harmony app, for $20/month, features a customizable avatar—as with the dolls, users can select skin tones, body sizes and shapes, hair, and clothing from a set variety of templates. Realistic skin tones vary on a gradient from pale white to deep brown, as well as more fantastic shades of blue and green. The avatar has a conversational voice assistant with four English-based accents in a male or female voice. The Harmony design team is currently working on connecting the app to a doll using a Bluetooth skull cap; the doll will eventually feature a robotic head with movable and adjustable facial affect to accompany the voice conversation, fusing the physical doll with the virtual avatar.

Janelle Monaé’s “Cindi Mayweather,” from The Archandroid album (2010)

As Alison Reed and Amanda Phillips have astutely noted, digital skin swapping in avatar design may promote a “racial ventriloquism,” the loose transposition of faces and skins in digital performances emphasizing racial caricatures and difference. In their acerbic analysis of the history of rotoscoping, they argue that the technology employs a notion of “additive race,” the messy displacements between racialized human bodies and their hyper-racialized avatar or cartoon forms: the “realism” portrayed by motion capture technologies “so often rely on the logics of white supremacy to ground reality in either the transparent universality of whiteness or the embodied specificity of POC—what we call additive race, the reduction of racialized difference to a matter of style.” Lauren Michele Jackson has more pointedly called such moves “digital Blackface,” speaking to the echoes of minstrelsy in the new generation of artificially generated Instagram “avatar models” like Shudu and Lil Miquela. Shudu, a Black female avatar, is designed and operated by the white graphic artist Cameron James Wilson, who has been praised for the beauty and life-likeness of the character and receives commercial contracts for Shudu to model various fashion products.

Harmony A.I., Shudu, and Lil Miquela

I focus on robotic and digital skin as a contact surface through which both desire and punishment are negotiated. Skin is a boundary zone, an interface demarcating difference and closeness. Digital skin often stands in for race, making the racial identity of dolls, robots, and avatars material through specific tonal swatches. The ease of customizing and swapping skin tones with avatars and (more expensive) dolls adds a layer of personal intimacy to the design. Users get to play at being designers of their own erotic experiences through the wielding of specific decision-making power over dolls’ skin and race. In such ways dolls are brought “close,” into proximity as intimate companions.

Such comments accumulate new meaning in light of recent legislation policing the circulation of ‘child-like’ small sex dolls. A landmark case in the UK (1) in July 2017 ruled the import of childlike dolls as “obscene,” setting the tone for subsequent legislation such as the CREEPER Act in the United States, which passed the House in June 2018. The CREEPER (“Curbing Realistic Exploitative Electronic Pedophilic Robots”) Act opens with eight ‘findings,’ beginning with these two:

- There is a correlation between possession of the obscene dolls, and robots, and possession of and participation in child pornography.

- The physical features, and potentially the “personalities” of the robots are customizable or morphable and can resemble actual children.

The act’s language specifically links interactions with “obscene” dolls to a proclivity for images of child sexual abuse. Further still, this correlation is framed around the ability to “customize” dolls to appear child-like. In my interviews with the doll company in California, designers emphasized that they refused to sell child dolls, despite occasional customer requests, and drew the line at their “petite” model. The petite model, they explained, is designed with large breasts to clearly define it, in their opinion, as an adult doll. Nonetheless, the guidelines for ‘child-like’ remain vague, as both an aesthetic and juridical category.

As I continue this fieldwork, I consider these implications of tying doll customization to potential violence, as well as the significance of skin—silicone or digital—for demarcating the boundaries of intention: How does the ability to customize race through skin tones leverage certain erotic expectations? How might the nexus of virtual avatar and physical doll produce new attitudes toward customization? How do designers make specific choices to highlight certain aspects of customization over others, with an attention to sexual attraction and companionship?

Note

(1) Police attention to the purchase of small dolls hinges upon an expectation that only suspicious potential offenders would purchase such items. Since early 2016, UK Border Force officers have seized 123 dolls and charged seven people with importing them. Of the seven men charged with importing the dolls so far, six also face child porn allegations after customs officers working with the UK National Crime Agency’s Child Exploitation unit conducted searches of their homes. A deputy director for intelligence operations on the UK Border Force explained that “What’s critical, I think, for this investigation, these items were going to individuals…who were committing other offences in relation to harm of children. They were also, critically, people who were otherwise unknown to UK law enforcement in having an interest in sexual activity with children. By identifying these importations, working with partners, what we’ve identified is a whole set of people with interests in sexual activity with children who were completely unknown.”

2 Comments

“Blade Runner, are often hypersexualized automatons who augur the apocalyptic ends of men’s capitalist, technological excess. Janelle Monaé’s reinterpretation of Maria as Cindi Mayweather, the Afrofuturist ‘archandroid,’ highlights how robots have typically served as vessels for white masculine anxieties around enslavement, consent, and freedom.”

I don’t know why you’d say that for Blade Runner. Blade Runner is not an apocalyptic end. Its dystopia is instead marked by a promise for future – more than human entanglements for creating a vibrant world. The memory facility perhaps is the most symbolic of these entanglements. Joi, and the prostitute are but beings – enormously creative objects despite their subjectivity.

“Blade Runner, are often hypersexualized automatons who augur the apocalyptic ends of men’s capitalist, technological excess. Janelle Monaé’s reinterpretation of Maria as Cindi Mayweather, the Afrofuturist ‘archandroid,’ highlights how robots have typically served as vessels for white masculine anxieties around enslavement, consent, and freedom.”

I don’t know why you’d say that for Blade Runner. Blade Runner’s portrayal is not an apocalyptic end. Its dystopia is instead marked by a promise for future – more than human entanglements for creating a vibrant world. The memory facility perhaps is the most symbolic of these entanglements. Joi, and the prostitute are but beings – enormously creative objects despite their subjectivity.

1 Trackback