Editor’s note: This is the first post in an ongoing series called “The Spectrum of Research and Practice in Guatemalan Science Studies.”

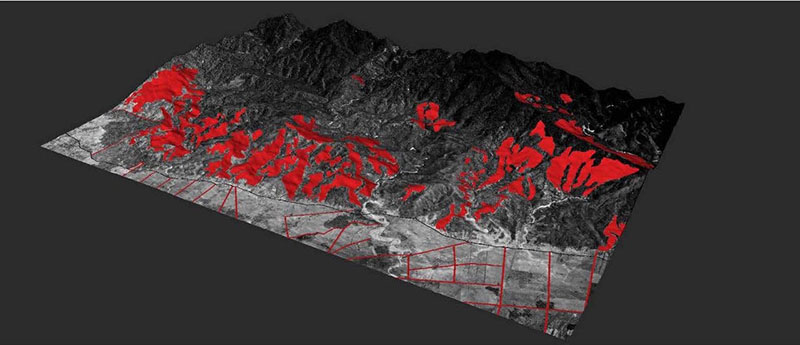

Forest analysis of scorched earth. Courtesy of Daniele Profeta. Princeton University, 2015.

On an early January morning in 2015 a group of lawyers from the Guatemalan NGO Mujeres Transformando el Mundo (Women Transforming the World), social workers, and human rights activists drove me and Megan Eardley (both of us PhD Candidates in Architecture History and Theory at Princeton University) through the department of Alta Vera Paz to reach the small village of Sepur Zarco. We were invited as architecture specialists after training under Eyal Weizman, who was a Global Scholar at Princeton University at that time. Weizman is the founder of Forensic Architecture, a research agency that uses the tools of architecture to conduct advanced spatial and media investigations in human rights violation cases. Traveling through what we thought would be a jungle, we encountered a landscape that was incredibly uniform, with vast cash crop fields of African Palm dominating our path. Although this image has become preponderant in the Global South, flex crops are just the last iteration of a long history of indigenous land dispossession and, in the case of Sepur, crimes against humanity by military forces. It is precisely in noting these changes in the landscape that altered forest patterns and absent villages can become tangible evidence of coordinated war interventions.[1]

In 2011, Mujeres Transformando el Mundo (MTM) became the associate legal team working with the public prosecutor in a case that involved the sexual and domestic violence against fifteen women of the Q’eqchi town Sepur Zarco. More broadly, the case was inscribed in an enormous effort by human rights advocates to bring to justice cases of human rights abuse during the internal war (1960-1996) under military rule, which was exacerbated once General José Efrain Ríos Montt became president (Naciones Unidas 1999). In the ten years between the creation of the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) and the Sepur Zarco case, human rights lawyers in Guatemala have become experts in bringing to justice powerful generals and politicians with the most infamous case being that against president Ríos-Montt. One key feature in the success of these trials was gaining international attention by involving highly respected international specialists at the forefront of their disciplines. Forensic Architecture’s work was introduced to MTM by a group of forensic anthropologists that had worked with Weizman in the past.[2]

The repressive campaign in Alta Vera Paz was mainly directed at dissidents and indigenous communities who were fighting to obtain legal tenement of their lands. The military sectioned areas they considered rebellious and entire communities were either relocated or isolated. Those living in these rural areas could only travel with a day pass and were subject to constant military incursions onto their land with the purpose of terrorizing those who would help the “communist” guerrillas. In Sepur Zarco, for example, a group of men who had organized to legalize their lands were violently dealt with by the military at the express request of rich landowners. Most of the men had been disappeared—their houses, animals and crops burnt to the ground, children and women abused, raped, or killed (Velázquez 2016).

Earlier in 2014, a lawyer from MTM contacted our group. Without having a clear idea of what Forensic Architecture meant by “spatial investigations,” the NGO sought to bring in architecture specialists to craft a model of the military outpost to convey more effectively the narrative of exploitation recounted by the women of Sepur. Together with Eardley and Daniele Profeta (who was an M.Arch. student on the design studio Brave New Now at Princeton University, led by Weizman and Liam Young), we decided to take the case under the supervision of Weizman (with Thomas Keenan and Eduardo Cadava as advisors), in which I, being the only Latin American, would be in charge to present the final report in the Corte de Mayor Riesgo de Guatemala, a court created to deal with special and high visibility cases.

By the time we were added to the case strategy, MTM had managed the case for four years. During this time, they had brought in nearly twenty specialists from anthropologists and sociologists, to medical doctors and psychologists. Through these collaborations, MTM (composed by mostly women) had developed an innovative approach for any trial involving sexual violence. It is often the case in small villages that publicly acknowledging and identifying as a victim of rape leads to ostracism. As a countermeasure to these repercussions, MTM devised a method in which all the women of the town would gather to talk to legal representation when they visited Sepur Zarco guaranteeing the anonymity of the fifteen plaintiffs (Impunity Watch 2017).

Architecture processes can become efficient tools in human rights advocacy. Some of the most basic tools that architects use in daily practice deal with the creation and perception of space. For instance, 3D software can help to recreate a place that exists only in the memory of the victims or to give legitimacy to their recount. A cloud map can act as a register of a moment in time and help to clarify details, distances, or relationships between actors and objects. Specialized software in acoustics, mechanics, engineering, pattern analysis, and so forth, can be powerful tools that add layers of information when combined with graphical representations. However, it is the characteristics to each case and the information available that determinate a specific method.

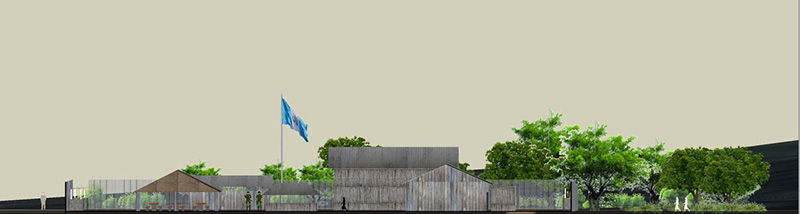

For this case, we turned to three scales of analysis: domestic, village, and jungle. The strategy was to demonstrate how these three narratives related closely to one another and to reveal how each scale influenced military logic and tactics. Dispossession, therefore, is not solely about land but also culture and race. Each scale had its own set of tools. The domestic scale focused on the 3D reconstruction of a military outpost built in Sepur Zarco, in an area donated by landowners, where the sexual and domestic abuse took place for six years (1982-1988). The scale of the village demonstrated how the systemic destruction of private property and social spaces (like the burning of the local catholic church) operated as a successful military tactic that violently deterred solidarity with those who protested the occupation. This was achieved by comparing aerial images before and after the war and contrasting them with testimony. The third scale of analysis, jungle, looked at the ecological transformation of the area of Izabal and Alta Vera Paz where scorched earth campaigns crippled the development of small local economies for years to come using remote sensing and satellite image analysis (Mendoza et al., 2016).

To work at the domestic scale (the military outpost), we gathered men from Sepur Zarco—who are often excluded from the meetings concerning the case—to recreate the site. Many of the men of Sepur had been forced to build the military post or had been taken there as kids with their mothers by the military. The first step was a simple exercise. The men were supposed to draw a map of what they considered relevant to the recounting of their experiences: the town, the area, the roads, and the military outpost all included. As a collaborative endeavor, the men, many of whom had not spoken in public about that time, started participating and taking turns to draw. A lively discussion emerged from this engagement. Details like measurements, quantities of objects, and building materials surfaced from memories little by little. Simultaneously, I was drafting a rough 3D model that they could see and correct as their memories came back to life. The model was not only an effective mnemonic device but created a space of trust and shared experience.

A group of men working with architecture experts in virtually reconstructing the military post in Sepur Zarco. Sepur Zarco, Guatemala, 2015. Courtesy of Elis Mendoza.

The research for the second scale, village, was conducted by visiting Sepur Zarco to collect images of its present state, gather physical evidence of the military outpost, and interview residents old enough to remember the village before the arrival of the military to the post. All this information was later contrasted with aerial images of land surveys taken before the war and through a rough 3D reconstruction that revealed the drastic transformation of Sepur. The third scale was developed through the use of remote sensing technology, satellite composite images, and aerial images from the land tenure archives. By analyzing patterns of growth and hues in the forest, the age of the jungle revealed a history of ecological violence.

The computer-generated 3D model of the military outpost served an additional and invaluable purpose in terms of evidence. By analyzing the building materials of the military outpost, using the multi-sourced data collected on its physical conditions, a set of sound emissions could be “tested” (with an acoustics analysis software) corroborating the plaintiffs testimony to present it in court as part of the forensic architecture expert report. By knowing the specific materials used to build each barrack we were able to identify the coefficient of sound transmission and understand how sound would travel within the outpost. For instance, a shout from a woman coming from behind a kitchen, where she was systematically raped, could be clearly heard in places where senior military officials were usually stationed. Architecturally reconstructing these scenes aided in establishing the criminal responsibility of one of the defendants.

Military outpost at Sepur Zarco. Courtesy of Elis Mendoza

As successful as the strategy of using architectural tools in the case of Sepur Zarco is, there is also a downside to it. After the trial, which was covered by national and international media, I was invited back to Guatemala to give a workshop about forensic architecture as a tool for accessing justice. I remembered a talk I had with a forensic anthropologist of Chihuahua, Mexico, when working on a case of disappearance. He complained about how CSI, the TV show, created unrealistic expectations that made people believe, for instance, that DNA was an uncontroversial evidence and every police station had access to it. As with these techniques, the forensic tools provided by architecture open new possibilities and narratives of access to justice. I have often been approached by legal teams that, regardless of the specific needs of the case, ask me to produce a point cloud 3D reconstruction, a 3D model, an animation of a crime, and so forth. Their intentions are not so much for forensic architecture’s capacity to reveal parts of the case that would otherwise remain hidden or unexplored but for its narrative capacity and its public performance. In places in which access to justice is rare like Latin America (in Mexico where I live, for example, 90% of crimes go unsolved),[3] a specialist with a novel set of tools runs the risk to be sought out by governments that want to give the appearance of seeking justice with the most innovative means (Animal Politico 2008). Although, in reality, they are just looking for a good show.

[1] To read about the ecological impact of scorched earth as a war strategy see Bronwyn Leebaw. “Scorched Earth: Environmental War Crimes and International Justice.” Perspectives on Politics 12, no. 4 (2014): 770-88.

[2] Corollary to the creation of the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (Comisión Internacional Contra la Impunidad en Guatemala, CICIG), founded in 2006, local NGO’s have become acquainted with a great number of legal experts.

[3] “Matar en Mexico: Impunidad Garantizada,” Animal Político, 2018.

References

Mendoza, Elis, and Megan Eardley, Daniel Profeta. “La violación de Sepur: Violencia de género en tres escalas arquitecturales.” Report for the Sepur Zarco case. Princeton University, 2016.

Naciones Unidas. “Guatemala memory of silence = Tz’inil na’tab’al: Report of the Commission for Historical Clarification Conclusions and Recommendations,” S.l.: Comisión de Esclarecimiento Histórico (CEH), 1999.

Paulo Estrada Velázquez. “El juicio de Sepur Zarco: la historia de las mujeres que exigen justicia por el pueblo q’eqchi,” Centro de Medios Independientes, 2016.

“The Changing Face of Justice: Keys to the Strategic Litigation of the Sepur Zarco Case,” Impunity Watch, Alliance to Break the Silence and Impunity, 2017.

1 Trackback