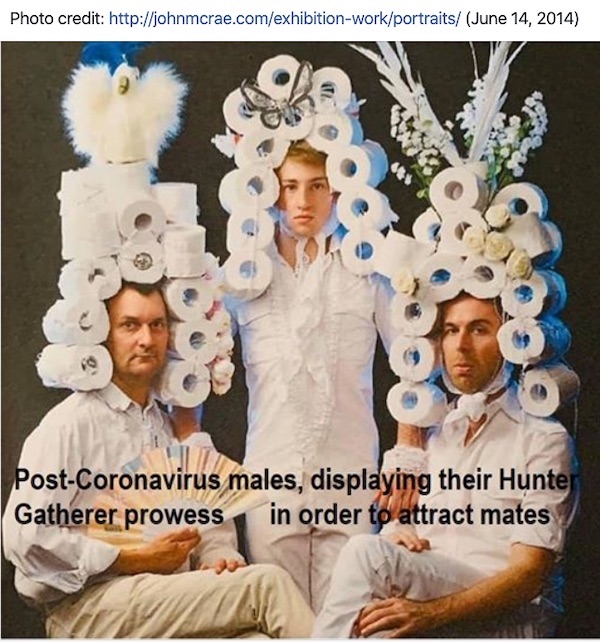

You would be forgiven for thinking that the first thing bought in a global crisis would be tinned, dried, and frozen foods; clean water; and medicines—things that enable the survival of you and your kin. Yet, when the number of COVID-19 cases in Australia hit 100 on March 10, 2020, it was the toilet paper aisles of supermarkets that were empty. Through what became the subject of memes depicting Australians sheltering from the ensuing pandemic wrapped only in toilet paper, and of men wearing lavish adornments of toilet paper rolls, daily bodily habits had hit center stage.

A meme shared on Facebook. March 20, 2020

The social and political history of shit tells us that the sense of the self is intimately attached to how we expel waste. In 16th century Europe, orders to keep waste inside one’s home and not thrown out into the streets, prefigured the division of socialization into public and private realms. As LaPorte states, “to touch, even lightly, on the relationship of a subject to his shit, is to modify not only that subject’s relationship to the totality of his body, but his very relationship to the world and to those representations that he constructs of his situation in society.” (LaPorte 1978, 29) The domestication of waste became part of a process of distinguishing ones status in hierarchies of civility. That is, contemporary human subjectivities became anchored forcefully to the ways in which we deal with shit. One could even make the argument that waste itself is a socially constructed concept. It is a value relation, not a particular kind of matter, that finds its origins in “new kinds of public-private involvements as well as a new kind of political authority.” (Biehl et al. 2007, 3)

The COVID-19 pandemic seems to have disrupted these forms of sociality enabled by and through commodities such as toilet paper, challenging the basic notion of self along the way. It is in this way that those of us accustomed to using toilet paper can understand the act of shitting hygienically into a flushing toilet, with 3-ply to wipe up any mess, as of utmost importance in times of crisis. The idea that one might become physically or symbolically closer to one’s own waste forcefully challenges established relationships to social hierarchies and the self—subjectivities. These social relations are legacies of “a long series of historical changes and moral apparatuses” with origins in colonial logics distinguishing between so called advanced civilizations and other cultures in the name of progress and development (Biehl et al 2007, 3). Throughout history we see numerous instances of how “segregation in the name of sanitation became a tool of colonial rule.” (Hecht, 2020) In the tropics, imperial forces would often distinguish themselves from the colonized through what were deemed to be superior civilizational hygienic practices (Anderson 2016).

Today, colonization through sanitation and hygiene takes on more opaque forms. In 2014, shortly after becoming Prime Minister of India, Nerendra Modi launched the Swachh Bharat (Clean India) campaign. The campaign aimed to achieve cleanliness across the country during the five years leading up to the one hundred and fiftieth birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi, on October 2, 2019. The primary mission of this campaign was to eradicate open defecation. With the support of the Prime Minister, and in the name of Mahatma Gandhi, India went about constructing millions of toilets. While on the surface this seems like a noble cause, the reality on the ground was much more complicated. Many toilets remain isolated brick outhouses with no running water, instead used for extra storage. Even if the toilets were working, some groups continued to be denied the use of them on the basis of their social status (Sagar 2017). Alternatively, in many cases people would simply prefer to shit in the fields. In other words, the construction of toilets does little to change social relations to human waste. Swachh Bharat simply attempted to rearrange the technologies of waste in ways that make hygiene in India legible to a global (i.e. colonial) standard. The pursuit of colonial modes of hygienic standards had become an excuse for “those in power to avoid the glaring class divisions and failures of the state” (Doron & Jeffrey 2018, 161).

But what does this all have to do with hoarding of toilet paper during a pandemic? The hoarding of toilet paper, along with inconsistencies of Nerendra Modi’s Swachh Bharat campaign, seem to reinforce LaPorte’s depiction of shit as central to the ideology of the modern human subject. The way in which we deal with our shit creates and transforms subjectivities. To be denied access to toilet paper only becomes unconscionable through the social significance of our relations to waste. As such, the hoarding of toilet paper reveals its importance as a modern object par excellence, in many ways highlighting moral values interwoven with uneven power and race relations. As Warwick Anderson (2006, 2) states in relation to hygiene and American imperialism in the Philippines: “experiencing hygiene thus could also be a means of experiencing empire and race.”

Anthropologist Nicholas Kawa has proposed that a good place to start in navigating the multiple ecological crises we face today might be to take better care of our shit (Kawa 2016). Yet as I have suggested above, taking care of one’s shit does not mean hoarding toilet paper, it means reconfiguring social relations away from hierarchies that build their foundations on the association of bodily waste with moral judgements. In other words, taking care of shit is “to be against the rhetorical or conceptual attempt to delineate and delimit the world into something separable, disentangled, and homogenous” (Shotwell, 2016) This means reimagining human waste as a important ingredient in the interconnectedness of life on Earth. While there is nothing inherently wrong with wiping one’s ass with paper, the panic that ensued from the idea that a scarcity of toilet paper might be around the corner, indicates shit’s continuing place in the disposition of colonized and colonizing human lives.

Acknowledgements

I’d like to thank Maya Weeks, Nicholas Kawa, Jennifer Barr and Baird Campbell for their generous feedback.

References

Anderson, Warwick. 2006. Colonial Pathologies: American tropical medicine, race, and hygiene in the Philippines. Durham: Duke University Press.

Biehl, J, Bryan Good, and Arthur Kleinman, ‘Introduction: Rethinking Subjectivity’, in Kleinman, A, Biehl, J, & Good, BJ (eds) 2007. Subjectivity: Ethnographic Investigations. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Doron, Assa and Robin Jeffrey. 2018. Waste of a Nation: Garbage and Growth in India. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Hawkins, Gaye. 2006. The Ethics of Waste: How We Relate to Rubbish. Sydney: University of Western Sydney Press.

Hecht, Gabrielle. 2020. ‘Human crap.’ Aeon. March 24. https://aeon.co/essays/the-idea-of-disposability-is-a-new-and-noxious-fiction

Kawa, Nicholas C. 2016. ‘Shit.’ Theorizing the Contemporary, Fieldsights, April 6. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/shit

LaPorte, Dominique. 1987. The History of Shit. Translated by Rodolphe el-Khoury and Nadia Benabid. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Sagar. 2017. ‘Down the Drain: How the Swachh Bharat Mission is heading for failure’, in The Caravan. May 1. https://caravanmagazine.in/reportage/swachh-bharat-mission-heading-failure

Shotwell, Alexis. 2017. Against Purity: Living Ethically in Compromised Times. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.