After lunch on the day I arrived at Casa Begoña Migrant Shelter in Matamoros, Tamaulipas, México, Doña Paquita, a shelter director, came to fetch me from the comedor, or the dining space, outside the back of the shelter.[1] “I want clear information so I know what to tell El Padre [the priest] in case he asks about why you are here.”

She stopped walking once we were in the waiting room in front of the kitchen and quickly pointed to the video camera at the left corner. “El Padre sees everything. The camera is always on, it’s recording and transmits to his office.”

“Of course, glad to talk about my plans while here,” I replied, trying to hide the shock in my face at learning that I and everyone else at the shelter were being watched.

Later that day, Doña Mariela, a shelter worker, gave me a tour of the bodegas where the produce and clothes provided to newly arrived migrants are stored. She conducts daily inventory, and food and clothes are donated almost every day; they must be washed and stored properly, she told me. “Did they tell you about the cameras?” Doña Mariela asked as we walked to the very back of the shelter where the bodegas are located.

“Yes, Doña Paquita mentioned them.”

“Good, so you know.” Doña Mariela continued. “He sees everything we’re doing, so we must always be doing something. If he sees us not working, he’ll call and ask what’s going on.”

An empty comedor at Casa Begoña where migrant guests gather to eat during breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Everyone must clean up after themselves once finished. Photo by author.

In detailing my experience with video cameras at Casa Begoña, I want to focus our attention to the everyday ways surveillance is deployed as a form of disciplinary power (Foucault 1995) that helps shelter staff maintain order in spaces where migrants convene and are aided. The US-Mexico border is often articulated as “the scene of ostensible crime fighting” (De Genova 2015) where the Border Spectacle of migrant illegality and exclusion are hyper visibilized in news and social media. Similarly, scholarship on militarized policing and surveillance has emphasized concrete practices and encounters at the border (De Genova 2002 and 2015; De Leon 2015; Dorsey and Diaz-Barriga 2020; Jusionyte 2018; Inda 2006; Rosas 2012), including an increasing reliance on automated and biometric technologies (Adey 2012; Dorsey and Diaz-Barriga 2020; Goldstein and Alonso-Bejarano 2018); Schaeffer 2019). While all this is important to document, in my own work, I explore how surveillance is deployed in sites that are usually less visible, such as in migrant shelters (which are rarely open to the public) and conducted through mechanisms not readily interpreted as surveillance technologies. When they’re mentioned in the media, especially after the 2019 Migrant Protection Protocols resulted in mass immobilization of migrants/refugees[2] in México, shelters and camps—organized around the principle of humanitarianism—are rarely problematized as sites of border surveillance and management. My intention is not to demonize shelter and camp directors and workers/volunteers who contribute so tremendously to the wellbeing of migrants as they journey across borders and navigate exclusionary Mexican and US asylum laws. Individuals like Doña Paquita and Doña Mariela, like so many others I met, have their own complex migration histories and reasons why they do the work that they do. Rather, I’m interested in illuminating the ways in which migrant/refugee life and mobility are layered with experiences and encounters embedded within socialites that operate in sites of surveillance, in this case, along Mexico’s northern border.

Surveilling (Im)mobilities

At first, I didn’t know what to make of this emphasis on the cameras at the shelter despite my initial sense of shock. Two weeks later I found out how serious Doña Paquita and Doña Mariela’s warnings were when I was rebuked by El Padre for resting my aching feet and lower back while taking a break on a hot and humid day. In retrospect, my shock at the realization of the shelter’s use of video cameras was naïve. Migrant shelters like Casa Begoña function as sites of disciplinary and social control despite—or maybe because of—their sincere intentions of helping migrants and asylum seekers. After all, migrant shelters in México tend to be extremely careful of who enters and exits since individuals involved in organized-criminalized groups usually hang out nearby, so understandably, shelter staff must take precautions and resort to practices of containment and security for their protection and that of migrant guests. This renders migrant shelters as sites of what Simone Browne calls “racializing surveillance,” spaces “where surveillance practices, policies, and performances” (2015:16) reproduce racializing norms and power that define who or what is acceptable. This penchant for order and discipline was evident as soon as Doña Mariela gave me a tour of the bodegas and explained the shelter’s functions. There are twenty rules written down on a large wooden sign at the shelter entrance that migrants must follow while in residence. Interestingly, it was not uncommon for an individual or a group of asylum seekers, for example, to be kicked out for bad behavior or to leave because of the strict rules in place.[3]

In Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Michel Foucault writes that the individual is molded into a social order “according to a whole technique of forces and bodies” (1995: 217). Studying such techniques of control and surveillance necessitates a study of power relations (Andrejevic 2015: xi). On my first day at Casa Begoña—before my encounter with the video cameras—I noticed how power differentials existed and operated at several levels: between the priest and staff, between staff and migrants, and between state forces, staff, and migrants. My presence as an ethnographer added another layer of power to reckon with (at least for me). Tellingly, migrants who stay at shelters like Casa Begoña must write down their names, gender, nationalities, age, and purpose in a log whenever they leave to wait at the International Bridge for their name to be called or run an errand at the store. They must ask for permission or notify someone that they’re about to step out. If they don’t, they’ll be scolded by the shelter worker who opens the doors for them, as the doors always remain locked. Once the evening comes and the night settles, no one’s allowed to leave the shelter until the doors open the following morning. Migrants can only head out into the city for private business once their sleeping areas are cleaned, their beds made, they have eaten breakfast, and joined in early morning prayer service. Migrants and asylum seekers are at the receiving end of the disciplinary power continuum in migrant shelters.[4] A whole technique of forces and (migrant) bodies.

“It’s as simple as that,” Doña Mariela explained to me. “If they don’t like it, they always have the option to leave. We try to help them but if they don’t want the help, we don’t force them to stay.”

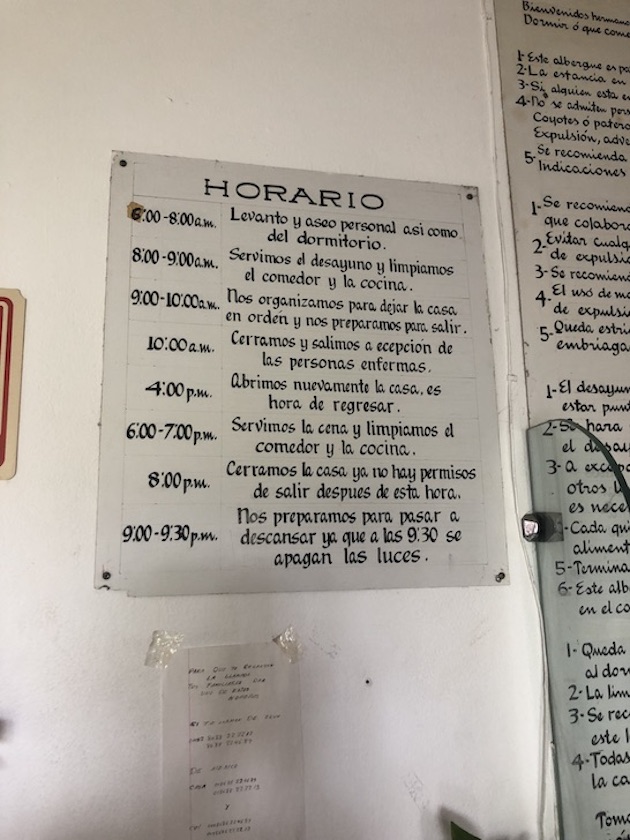

The shelter schedule hangs next to shelter rules at Casa Begoña. From 6:00 AM to 9:30 PM migrant guests are expected to abide by schedule duties and demands. Photo by author.

I was told about an occurrence in 2018 when a group of asylum seekers from the LGBTQ+ caravan made their way to the Matamoros border. They stayed at Casa Begoña. Doña Mariela, half in disgust, explained: “We don’t judge them and open our doors to everyone. You know, they have a disease of the mind, that’s why they’re like that.” I held my tongue back as she recited the story of how they had brought alcohol to the shelter, something that’s discouraged and disciplined by removing them from the shelter. “We allowed some of them to stay here and they decided to bring beer and cigarettes [which can be smoked outside in the back] and some got into an argument. The ones who started the argument left and the next day we caught another two having sex, so we told them to leave as well. Later that night, we caught a friend of theirs giving them some towels and toiletries through the window, so we told all of them to leave.” Doña Mariela kept explaining: “When they left, they didn’t clean up after themselves, left their mess and used condoms in the trash. It was disgusting. That’s part of the rules when you’re here, even if you’re a married couple, you must be abstinent. Those are the rules and when you’re here you need to respect the shelter and everyone in it. They had no respect.”

I didn’t want to question or disrespect Doña Mariela, so I wrote down what she told me in disbelief and shock at her commentary and explanation. I replied with an insincere, “That’s true” and we kept talking.

Doña Mariela’s comments and the overall ethos of Casa Begoña have made me wonder about the methods humanitarian spaces put in place to deliver aid and relief to migrants/refugees tend to reproduce certain oppressive structures. Rachel Dubrofsky and Shoshana Magnet (2015) remind us that a feminist understanding of surveillance studies places surveillance as foundational to structural systems that produce disenfranchisement. These technologies and practices normalize and maintain whiteness, ableism, capitalism, and heterosexuality.

If we take the case of the LGBTQ+ migrants who were kicked out of the shelter, we see how discipline and surveillance at Casa Begoña rely on similar normalizing practices. Additionally, while the video cameras extend Casa Begoña’s reach into the digital realm, analog surveillance practices such as the physical act of seeing and watching over migrant lives by shelter workers never ceases. In fact, the cameras augment the surveillance and control that they must enact in the everyday, through documentation in logs and other paperwork, to maintain shelter rules and order.

Administrative practices often do the work of surveillance. Beyond video cameras, there are ledgers, logs, reports, lists, and legal paperwork that circulate at Casa Begoña as personnel document everyone who passes through the shelter and its daily occurrences. This includes food that is prepared, the clothes and supplies that are donated, in addition to who uses the phone and computers to communicate with relatives. Kevin Walby and Seantel Anaïs (2015) propose using “institutional ethnography” to observe and critique the ways in which gender inequalities and power relations are reproduced within organizations. As a Marxist materialist approach, it allows us to focus “on how organizations categorize, classify, and label people” (213) through an analysis of texts and their activation. Institutional ethnography as method allows researchers to explicate how “texts coordinate surveillance practices in organizations” (214) like at Casa Begoña and other spaces where migrants wait for their asylum cases and futures to unfold.

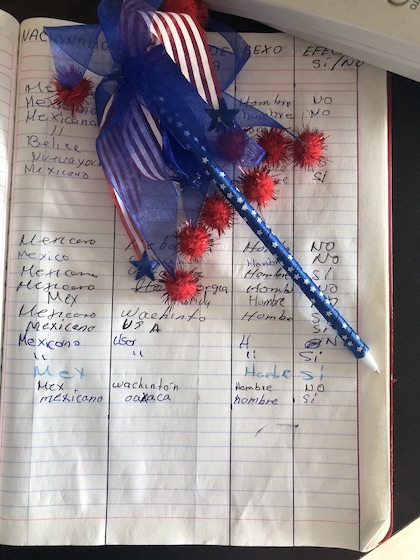

A phone log with columns detailing nationality, call destination, sex, and whether or not call was answered. Photo by author.

Toward Surveillant Materialities

State and non-state organizations rely on surveillance to regulate the mobilities of non-citizens within Mexican territory. Understanding these dynamics requires an observational shift from the obvious forms of border surveillance technologies (drones, Aerostat blimps, digital cameras on border walls, in police vehicles, helicopters, and face-to-face encounters with agents) to the range of active texts that are produced, circulated and contribute to the surveillant assemblage (Haggerty and Ericson 2006) on migrant (im)mobility in México. I think of these textual surveillance practices as part of broader surveillant materialities that are in line with Browne’s formulation of racializing surveillance and that function “‘like a microscope of conduct’” seeking to “objectify, transform, and improve individuals through architectural arrangements, registration, examination, and documentation” (2015: 41). While Browne’s analysis is grounded in the vicious regulation of black mobility within the slave system through the use of technologies like lantern laws, branding, the pass system, and runaway notices, it is useful to think of how similarly print technology operates in the context of asylum and humanitarianism in contemporary México. Institutional ethnography helps us understand how texts animate practices of surveillance and reveals the ways in which migrant/refugee life and (im)mobility are constantly subject to discipline and management by both state and non-state actors under yet another era of border and migration control between México and the US.

Notes

[1] All names of places and people are pseudonyms to protect their identities.

[2] While there are important legal differences between “asylum seeker,” “migrant,” and “refugee,” I use the first two interchangeably as done so my interlocutors. I use “migrant/refugee” with the awareness that individual distinctions often blur since “every act of migration to some extent… may be apprehensible as a quest for refuge, and migrants come increasingly to resemble ‘refugees,’ while, similarly, refugees never cease to have aspirations and projects for recomposing their lives and thus never cease to resemble ‘migrants’ (De Genova, Garelli, and Tazzioli 2018).

[3] Many migrant shelters, though not all, are managed by the Catholic Diocese which works in tandem with the Pastoral Commission on Human Mobility (PCHM), the National Migration Institute (INM), and the Mexican Commission on Refugee Assistance (COMAR).

[4] Still, they resist and refuse in their own way, as I saw in the case of Nelson that I detail elsewhere and in spaces where activists and aid organizations collaborate to empower them. Yet at some shelters, if migrant guests step out of bounds, or if they realize the space is not one in which they feel welcome due to the rules, they are kicked out or leave on their own accord.

References

Adey, Peter. 2012. “Borders, Identification and Surveillance: New Regimes of Border Control.” Routledge Handbook on Surveillance Studies. Kristie Ball, Kevin Haggerty, and David Lyon (eds). Routledge Press.

Andrejevic, Mark. “Foreword.” In Feminist Surveillance Studies. Rachel E. Dubrofsky and Shoshana Aimelle Magnet (eds). Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Browne, Simone. Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

De Genova, Nicholas, Glenda Garelli, and Martina Tazzioli. 2018. “Autonomy of Asylum? The Autonomy of Migration Undoing the Refugee Crisis Script.” The Southern Atlantic Quarterly 117(2): 239-265.

De Genova, Nicholas. 2015. “The Border Spectacle of Migrant ‘Victimisation.’” openDemocracy: Free Thinking for the World. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/beyond-trafficking-and-slavery/border-spectacle-of-migrant-victimisation/. Accessed May 15, 2020

De Genova, Nicholas. 2002. Working the Boundaries: Race, Space and ‘Illegality’ in Mexican Chicago. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

De Leon, Jason. 2015. The Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail. University of California Press.

Dorsey, Margaret and Miguel Diaz-Barriga. 2020. Fencing In Democracy: Border Walls, Necrocitizenship, and the Security State. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Dorsey, Margaret and Miguel Diaz-Barriga. 2020. “Algorithms, German Shepherds, and LexisNexis: Reticulating the Digital Security State in the Constitution-Free Zone.” In Walling in and Walling Out: Why Are We Building New Barriers to Divide Us. Laura McAtackney and Randall H. McGuire (eds). Albuquerque: University of New México Press.

Dubrofsky, Rachel E. and Shoshana Aimelle Magnet. 2015. Feminist Surveillance Studies. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Foucault, Michel. 1995[1977]. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Vintage Books.

Goldstein, Daniel M. and Carolina Alonso-Bejarano. 2018. “E-Terrify: Securitized Immigration and Biometric Surveillance in the Workplace.” In Bodies as Evidence: Security, Knowledge Power. Mark Maguire, Ursula Rao, and Nils Zurawski (eds). Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Haggerty, K. D., and R. V. Ericson. 2000. “The Surveillant Assemblage.” British Journal of Sociology 51(4): 605-22.

Inda, Jonathan Xavier. 2006. Targeting Immigrants: Government, Technology, Ethics. Blackwell Publishing.

Jusionyte, Ieva. 2018. “Injured by the Border: Security Buildup, Migrant Bodies, and Emergency Response in Southern Arizona.” In Bodies as Evidence: Security, Knowledge Power. Mark Maguire, Ursula Rao, and Nils Zurawski (eds). Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Rosas, Gilberto. 2012. Barrio Libre: Criminalizing States and Delinquent Refusals of the New Frontier. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Schaeffer, Amaya. 2019. “Automated Border Control: Criminalizing the Hidden Intent of Migrant Embodiment. Kalfou: A Journal of Comparative and Relational Ethnic Studies 6(2):177-198.