Introduction: Why a zine?

Clara del Junco and Mathilde Gerbelli-Gauthier

In this post, we’re sharing some excerpts from Burnout: a zine about academia, travel, and climate change that we put together over the course of the past months, in the time freed up by the hiatus in travel. The excerpts we’ve chosen for Platypus include 1) Our C*****n F*******t Calculator, along with our reflections on the limited utility of any carbon footprint tool; 2) Part of an essay by Riley Linebaugh, putting academic air travel into the context of global inequalities perpetuated by academic institutions; 3) A comic by Hannah Eisler Burnett that documents her transatlantic trip on a cargo ship.

Detail of the cover of “Burnout: A zine about academia, travel, & climate change.” (CC-BY-NC 4.0 by Clara del Junco, Mathilde Gerbelli-Gauthier, et al.)

In December of 2019, I stuck a post-it note to my desktop computer: “MINIMIZE TRAVEL IN 2020″. This ultimately prophetic New Year’s resolution had emerged from an increasing uneasiness with the amount of travel that I, as a PhD candidate in chemistry, had been doing for the past few years. Initially thrilling for my broke, undergraduate self, the frequent flying—to visit far away family and friends, attend conferences and workshops—became physically and emotionally taxing. I found myself in a bind: I love traveling, and I find it necessary to sustain my relationships. Having lived a delocalized academic lifestyle for a decade, my friends and family are scattered throughout Europe and North America. And despite the broad recognition that climate change is an existential threat, plane travel is still an integral and largely uninterrogated feature of academic life.

Were my peers—other overworked, internationally mobile, leftist academics—feeling the same malaise? And what were they doing about it? I discussed this at length with my friend Mathilde, a math PhD student. At the time, she was flying monthly to maintain a long-distance relationship with her partner, also an academic, who had moved from Chicago to Baltimore for a postdoc. Not satisfied with our own answers, or lack thereof, we asked friends and colleagues—and one stranger from the internet—for reflections on academia, travel, and climate change. The wide-ranging result was this zine, Burnout.

The coronavirus pandemic has been a forced experiment in academia without travel. The negative consequences are clear, and—as Riley describes in the excerpt below—unevenly distributed. But several of the contributions in this zine explore the generative possibilities of immobility. Might we be better off staying put? Or is the issue more complicated? The zine is not comprehensive—in drawing on our networks, we have necessarily missed many perspectives. We hope it will seed conversations where more perspectives will be shared, and begin to connect people who are committed to reimagining academic institutions and keeping one another accountable to practices rooted in environmental sustainability and justice.

- Title image of the comic “La Española.” (CC-BY-NC 4.0 by Hannah Eisler Burnett)

- “La Española,” page 1. (CC-BY-NC 4.0 by Hannah Eisler Burnett) [3]

C****n f**tp***t calculation

Clara del Junco and Mathilde Gerbelli-Gauthier

The goal of this exercise is to think about your travel in the last year, both in terms of fossil fuel emissions and its effect on your life. In the first part, you will estimate the emissions related to your plane travel in the last year. In the second part, we provide several prompts to help you reflect on the numbers you obtained from the calculation and the role of plane travel in your life.

Calculation

Calculating the fossil fuel emissions of the airplane travel of an individual is complicated. It depends on many factors: the aircraft model, length of the trip, seating configuration of the plane, etc. Shorter flights have higher emissions/mile ratios because a lot of fuel is burned at take-off and landing. Many carbon calculators also include a multiplier accounting for the fact that greenhouse gases released at high altitude have a magnified effect on global warming. Our method, which is based on the air travel section of Berkeley’s Cool Climate Calculator[1] aims to be a compromise between accuracy and simplicity, and the resulting number should be treated as a ballpark figure for your year’s fossil fuel emissions due to flying, and not an exact number.

We’ve divided the process into three steps: brain dump, flight distances, and carbon emissions. To give you an idea of what the calculation should look like, we’ve included an example at the end of the exercise.

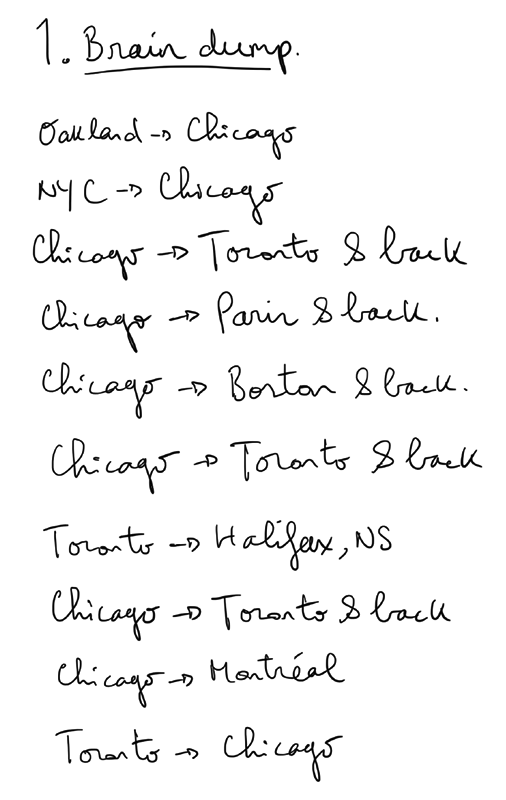

- Brain dump: Write down all the flights you have taken in the past year. If your flight was not direct, write each leg of the trip separately: for a flight from Chicago to Montreal with a stopover in Toronto, write Chicago-Toronto and Toronto-Montreal.

- Flight distances: Look up the distance of each flight online. List it in the appropriate table for short, medium, long, or extended flights.

- Computing emissions: For each category, add all the kilometers/miles for that category and note it in table 3a or 3b. Multiply this number by the gCO2 conversion factor provided in the third column and write down the result in the fourth column. Add all these numbers up. This number is in grams so it should be large. Divide it by 1 million to rewrite it in tonnes.

1. Brain Dump

2. Flight Distances

Short flights: < 400 miles or 650 km

| Trip | Distance |

|---|---|

| Total Distance |

Medium flights: 400 - 1500 miles or 650 - 2400 km

| Trip | Distance |

|---|---|

| Total Distance |

Long flights: 1500 - 3000 miles or 2400 - 4800 km

| Trip | Distance |

|---|---|

| Total Distance |

Extended flights: > 3000 miles or 4800 km

| Trip | Distance |

|---|---|

| Total Distance |

3. Calculation

| Type | Total Distance (km) | gCO2 per km | Subtotal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short flights | 320 | ||

| Medium flights | 254 | ||

| Long flights | 224 | ||

| Extended flights | 214 | ||

| Total gCO2 | — | — | |

| Tonnes gCO2 | (gCO2 / 1,000,000) | — |

| Type | Total Distance (miles) | gCO2 per mile | Subtotal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short flights | 508 | ||

| Medium flights | 408 | ||

| Long flights | 362 | ||

| Extended flights | 344 | ||

| Total gCO2 | — | — | |

| Tonnes gCO2 | (gCO2 / 1,000,000) | — |

Example Calculation

Brain Dump:

2. Flight Distances

There are no short flights in this example.

Medium flights: 400 - 1500 miles or 650 - 2400 km

| Trip | Distance |

|---|---|

| Chicago → Toronto | 435 miles |

| Chicago → Toronto | 435 |

| Chicago → Toronto | 435 |

| Toronto → Chicago | 435 |

| Toronto → Chicago | 435 |

| Toronto → Chicago | 435 |

| NYC → Chicago | 796 |

| Boston → Chicago | 950 |

| Chicago → Boston | 950 |

| Toronto → Halifax | 787 |

| Chicago → Montreal | 750 |

| Total Distance | 7278 miles |

Long flights: 1500 - 3000 miles or 2400 - 4800 km

| Trip | Distance |

|---|---|

| Oakland → Chicago | 2125 miles |

| Total Distance | 2125 miles |

Extended flights: > 3000 miles or 4800 km

| Trip | Distance |

|---|---|

| Chicago → Paris | 4152 miles |

| Paris → Chicago | 4152 |

| Total Distance | 8304 miles |

3. Calculation: Imperial Units

| Type | Total Distance (miles) | gCO2 per mile | Subtotal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short flights | 0 | 508 | 0 |

| Medium flights | 7278 | 408 | 2969424 |

| Long flights | 2125 | 362 | 769250 |

| Extended flights | 8304 | 344 | 2856576 |

| Total gCO2 | — | — | 6595250 |

| Tonnes gCO2 | (gCO2 / 1,000,000) | — | 6.6 |

Reflection

Here is some data to put your number in context. The yearly per capita CO2 emissions (not just from flying) of some of the countries mentioned in this zine are: Brazil (2.4 tonnes), France (5), Germany (9.1), India (1.9), Kenya (0.4), and USA (16.1), with a global average of 5[2]. Of the 16.1 tons emitted by “the average person” in the USA, 1.65 come from air travel, with the rest coming from other forms of transportation, food, goods and services, heating, cooling, electricity, construction, and so forth, according to the Berkeley Cool Climate Calculator. We suggest checking it out if you are interested in further details about how fossil-fuel intensive different parts of your life are, and how your emissions compare to the national average.

Prompts for reflection:

- What is your initial reaction to this number?

- What role does travel play in your life? How does it affect your body, your moods, your research, your relationships, etc?

- Imagine flying 25% less, or 50% less. Which trips would you give up? What would be the effect of those decisions?

- Imagine professional practices that rely less on flying. What are they? How can you move towards them?

- Imagine changes in your academic institution that could address the climate crisis, such as disinvesting from the fossil fuel industry. How can you create them?

In the process of writing this exercise, we found out that the term “carbon footprint” was popularized by BP as a way to shift responsibility for climate change from the fossil fuel industry onto individuals. We have decided to include this exercise in the zine anyway (though not using the phrase “carbon footprint”) for two reasons. First, because we think that a personal reckoning with the proportion of our emissions that comes from plane travel is a way to begin reflecting on the changes that we can make to prepare ourselves for life in a future world without fossil fuel-powered travel. More importantly, we think that the results of the exercise highlight how the infrastructures and institutions that govern our lives limit both our choices as individuals, and the impact of those choices. How can we change these systems to provide ourselves with viable low-emissions ways of living? What collective action will this require?

We are grateful to Jeff Johnston, Gabriel Lefebvre-Ropars, and Megan Roda for feedback on earlier versions of this exercise.

- “La Española,” page 2. (CC-BY-NC 4.0 by Hannah Eisler Burnett) [4]

- “La Española,” page 3. (CC-BY-NC 4.0 by Hannah Eisler Burnett) [5]

Some Reflections on Academic Mobilities & the Climate Crisis (Excerpt)

Riley Linebaugh

I returned to Germany (88.8kg CO2) in the fall and shortly after attended the African Studies Association conference in Boston (776kg CO2) to present some of my research. The conference was the first time in my 8 years in higher education that I was surrounded by such a magnitude of Black scholars. On a round table on decolonizing African studies, I listened to psychology professor Glenn Adams describe how he teaches his largely white students at the University of Kansas about epistemological violence. This focus on epistemology redirects the scholarly tendency to address the question “What is my research about?” to “What is the function of this research? What does it do?” This form of examination is especially crucial regarding the climate crisis, global capital, and coloniality.

The question of academic air travel must be answered taking into consideration global inequities and how they are perpetuated by academic institutions. A universal suggestion to restrict scholarly mobility risks further alienation of scholars from the global South from the resources consolidated in the North and performs the work of racist border regimes. Institutions and individuals in North American and European higher education contexts face a greater responsibility of epistemological and behavioral transformation to combat the climate crisis. How can our knowledge-work sustain life? This reflection on the cost and value of my academic travels reveals how academic institutions reproduce elite structures by default, for example, through access to “networks” and funding. The CO2 cost of my academic travel is inextricably linked to the bigger costs associated with forms of global extraction. How can reshaping academic mobility service a degrowth in CO2 expenditure and reparative redistribution in both a material and interpretative sense?

There are practical steps that are within reach of graduate students: Demand/seek funding for lower carbon transport (i.e. trains). Demand the use of video technologies wherever possible. Diversify citations to increase the intellectual mobility of scholars from around the globe. Collaborate with other junior scholars from the global South by digitally sharing research materials. Support open access publications and open source research tools. Familiarize yourself with the ways in which your discipline is uniquely entangled in the climate crisis. Prioritize global equity measures as you grow into your career. Refuse to see your scientific work as separate from the material realities around you. Listen to those who have been struggling against ecological devastation for centuries, very often those dispossessed by settler colonial projects. These suggestions are at odds with academic environments that produce individualism and precarity through competition and scarcity. Regardless of discipline, transforming our academic environments is essential to climate justice. Examining academic air travel is a useful way to map out individual and institutional carbon impact on a global scale. However, alone, it is not a reliable metric for climate damage. What aims is that mobility serving? John La Rose’s journey from Trinidad to Britain had a similar carbon cost as the flight carrying colonial archives from the Caribbean to London. One journey resulted in decades of international anti-racist activism and the other in decades of suppressing documentary evidence of colonial exploitation.

“La Espanñola,” page 4. (CC-BY-NC 4.0 by Hannah Eisler Burnett) [6]

Notes

[1] https://coolclimate.berkeley.edu/calculator; see the methodology for details.

[2] https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/9d09ccd1-e0dd-11e9-9c4e-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

[3] Handwritten text below the drawing reads: “In the summer of 2018, I traveled to Europe for a conference on political ecology. In an effort to travel slower—and less wastefully—a friend and I took a cargo ship back to the U.S.”

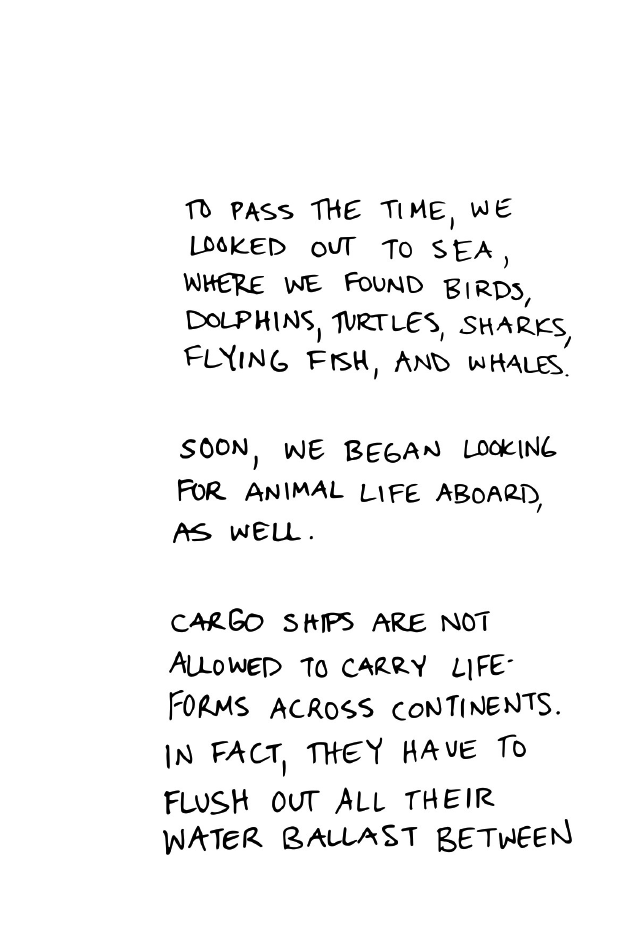

[4] Handwritten text reads: “To pass the time, we looked out to sea, where we found birds, dolphins, turtles, sharks, flying fish, and whales. Soon, we began looking for animal life aboard, as well. Cargo ships are not allowed to carry life-forms across continents. In fact, they have to flush out all their water ballast between” (continued in note 5).

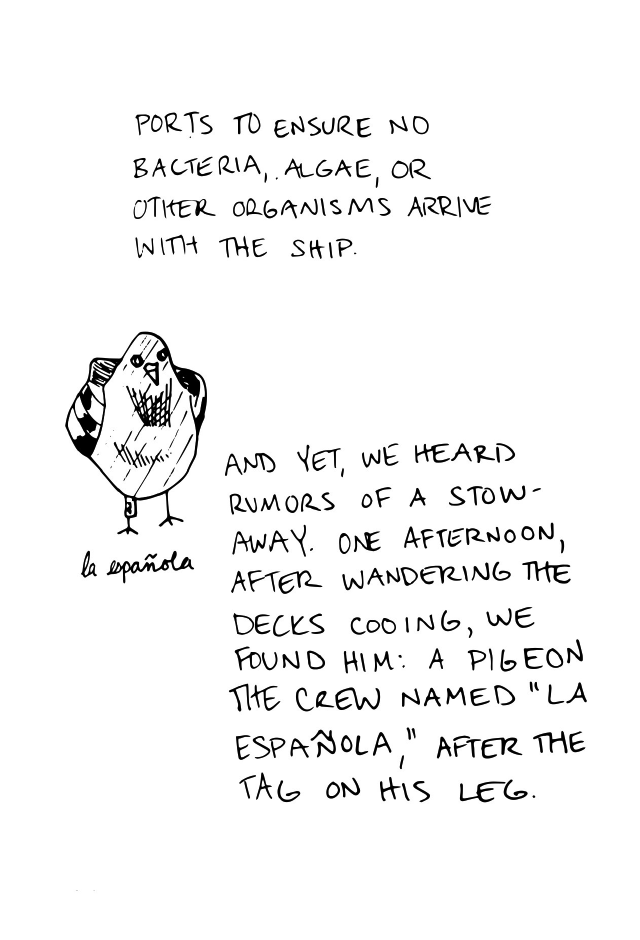

[5] Handwritten text reads (continued from note 4): “ports to ensure no bacteria, algae, or other organisms arrive with the ship. And yet, we heard rumors of a stow-away. One afternoon, after wandering the decks cooing, we found him: a pigeon the crew named ‘La Española,’ after the tag on his leg.”

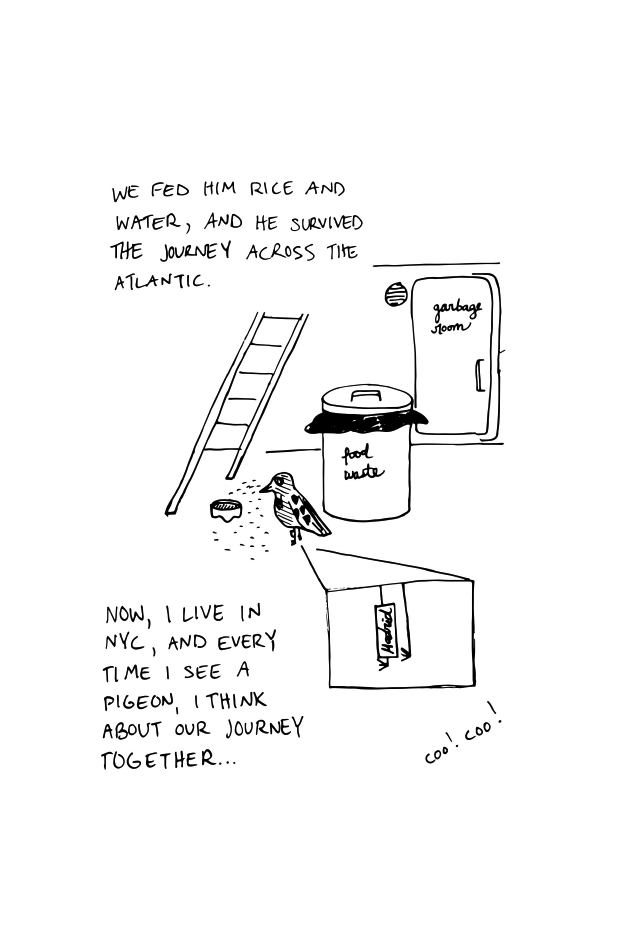

[6] Handwritten text reads: “We fed him rice and water, and he survived the journey across the Atlantic. Now, I live in NYC, and every time I see a pigeon, I think about our journey together.”

![Black and white drawing and text. Two hands hold a pigeon against a pocket and a nametag that reads [redacted]. In large script across the bottom reads, "La Española."](https://blog.castac.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2021/01/burnout-1.png)

![Black and white drawing and text. A cargo ship viewed from behind. The ship's name reads [redacted]. There is handwritten text below the ship (see expanded description in Footnote 3).](https://blog.castac.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2021/01/burnout-2.png)